30th August 2022

The rise of darknet marketplaces (DNMs) illustrates the systemic failings of drug war enforcement. From the perspective of the hackers behind this technology, they have, in the last decade, marked a new frontier in undermining prohibitionist efforts to restrict the availability of illegal drugs. To be clear, the unregulated free market model these websites represent has little to do with Transform’s vision of legal regulation. Nevertheless, darknet users have undeniably pioneered - deliberately or not - models of harm reduction, which may offer useful lessons as we plot the course into a post-prohibitionist world.

In this blog, we explore some of these community-led harm reduction initiatives while considering their limitations and how they could be improved under a more formalised legal regulation model.

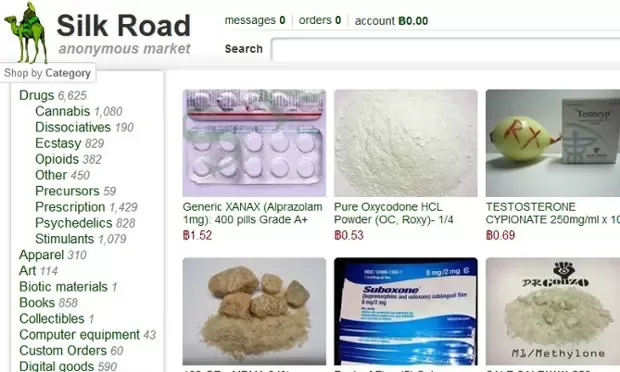

The form of anarchic direct action endorsed by many darknet hackers, known as counter-economics (a way of overthrowing state institutions using free market logic to strengthen underground economies), has been almost impossible to practice in the ‘real world’ because of the threat of police intervention. However, their dream of ‘opting-out’ became possible for the first time following an alignment of recent technological innovations. This new suite of tools – Tor (an anonymous web browser which hides a user's IP address), PGP (an encryption tool to hide sensitive information such as names and addresses), and Bitcoin (a decentralised, untraceable cryptocurrency) – enabled the creation of Silk Road, the first DNM launched in 2011, followed by a series of successors.

By creating a platform where users can communicate, browse, sell, and buy drugs anonymously by mail order – Silk Road, in a sense, legalised drugs by proxy (at least from a user perspective, even if legal jeopardy remained once in possession) – albeit in an unregulated format. Anyone who learnt how to use the technology (a relatively easy-to-negotiate barrier for most tech-savvy people) could order almost any illegal substance with discreet delivery. Paradoxically this newly afforded anonymous protection also opened up the possibility for transparency.

Unlike buying from someone selling on the street, with often no knowledge of what’s in the product, how strong it is, or how it affected previous customers – DNMs allowed a customer review model like that of Amazon or eBay. Users could post a star rating and a review of their purchase to inform other users. Many users also began publishing the results of their home-testing kits. This meant that if a vendor mis-sold or sold adulterated drugs, they would receive a surge of negative reviews and people would cease buying from them. This created a hierarchy of vendors in which the most reputable would ascend to the top, giving users some idea of who to trust.

Soon enough, some of the more reputable vendors employed drug testing services such as Energy Control – a lab in Spain which can legally publish the results of a test that the service users can verify with a specific code. This, alongside detailed pictures of the product, enabled users to have a good (though not exact) idea of what they were potentially buying and consuming.

With access to almost any illegal drug, including heroin and opioids, sharing of harm reduction information soon became a key feature of DNMs. Among the anonymous messaging boards and forums which orbit the marketplace, communities began to emerge. In the opioid forums, many posts asked how to use more safely, as well as how to quit and manage withdrawal. Hence, harm reduction became an essential part of the community – manifested not only in customer reviews and lab testing, but mass adulterant warnings, user-based guides, and even a darknet forum ‘Ask Me Anything’ session with Dominic Milton Trott, author of The Drug Users Bible. Centred around harm reduction and risk mitigation, Trott’s book follows the belief that “The first casualty of war is truth, and the war on drugs is no different” (Trott 2019).

Another example of the self-help ethos was in response to the growing opioid crisis, which was at the time the leading cause of accidental death in the US (Davis 2017). One vendor on a DNM called Alpha Bay began selling ‘recovery packs’; a collection of medications to help ease individuals through the maelstrom of withdrawal.

Another inadvertent harm reduction measure of the mail order model is the time delay between ordering and receiving drugs purchased on the DNM. This acts as a buffer period, encouraging customers to make informed choices and discouraging impulsive drug using and bingeing. This is one of the proposals in Transform’s Blueprint for Legal Regulation, “An order/pick up time delay would encourage forward planning of any drug taking, and thereby more responsible use and moderation. This would also help curtail binge use, by preventing immediate access to further drug supplies once existing supplies had run out. In some countries access to casinos is controlled in this way; membership is required for entry, but it is only activated the day after application” (2009: 52).

A more indirect harm reduction outcome of DNMs is the reduction in associated street crime. The nature of an online marketplace means that there is no physical transaction of drugs or money. For those who can access the DNMs this eliminates the potential threats - such as theft or assault - of interacting with an illegal street drug scene or unknown vendors.

Consequently, some of the testimonies of Silk Road collected in a 2013 study are not surprising:

“I now use it because the quality of drugs is so much better. Silk Road provides lab tested substances in which I know the quality. I can make a rational decision on what quantity to use to best minimise harm. You know what you’re getting and you can see feedback and honest advice from other buyers of the product. I’ll never use a street dealer again.” (Male 20-25 years)

“I don’t think it promotes new users because no one is taking the time and computer-knowledge to come to the ‘Silk Road’ if they’ve never used drugs before” (Female 26-30 years)

“You have to be patient and you have to be smart to get there and use it. BitCoin isn’t easy to get and use. You have to learn the ropes. But it’s totally worth it. It’s changed my life significantly.” (Male 26-30 years)

This anarcho-capitalist model is the latest mutation in the ‘survival of the fittest’ game of prohibition. The rise of DNMs demonstrates that people who use drugs and those who sell them will take increasingly sophisticated measures to avoid law enforcement. Even when markets, including the original Silk Road have been shut down, new DNMs have quickly emerged to replace them - the age old enforcement game of whack-a-mole merely transferring into the virtual arena.

The unregulated nature of this model does, however, present a series of unique risks and challenges:

Spoilt for choice – While most people who use DNMs are looking for small quantities of cannabis or MDMA, users are confronted with a supermarket-scale menu of substances of all kinds. From untested research chemicals and novel pharmaceuticals to crack cocaine and heroin. As the quote from 2001 film Blow suggests, “I went in with a Bachelor of marijuana, came out with a Doctorate of cocaine”. The seemingly limitless possibilities can be tempting for even the small-time cannabis user - especially as, when the value of the Bitcoin fluctuates wildly, users may find themselves with unexpected extra cash in their virtual wallet. Paired with the option to buy sample-size quantities which many vendors offer, the gateway to more risky drugs or drug using behaviours is a real one. Low prices of drugs at wholesale quantities can also prove tempting to those who see the possibility of profits from re-selling.

Competitive purity – There is a double-edged sword effect to a competitive free market system. As vendors compete for the best quality products, the market can become saturated with drugs of unexpected potency. In the case of MDMA, for example, ecstasy pills now commonly contain over 250mg (and occasionally over 300mg) of MDMA while the recommended safe adult dose is in the range of 80 – 120 mg. Despite being pure and unadulterated, the unexpectedly high potency of drugs such as these - sold as pills for individual use - can present very real dangers.

Drug safety – It is true that DNMs have pioneered a purchaser/vendor feedback model that is hard to replicate offline in the absence of easily accessible drug checking and remains unavailable to most people who use drugs. However, despite these efforts, the nature of operating illegally means that no product’s contents can be reliably verified to a level that legally regulated markets offer for consumers.

Gateway to other forms of crime – Many DNMs offer more than just drugs. Alongside their extensive menus, users can also find access to fraud services such as ‘carding’, fake documentation, hacking tutorials, and counterfeit currency. Also on offer are stolen goods, and in some rare cases, weapons.

Loss of money - Bitcoin sent to vendors does not always guarantee a product will be dispatched or arrive. High-profile cyber busts of major DNMs have often led to losses, as have individual vendors who turn out to be scammers, and on a few occasions - entire scam DNMs disappear with more substantial funds (and in all such cases, users obviously have no recourse to law enforcement to attempt to recoup any losses).

As such, many of the challenges previously associated with more conventional illegal drug markets have continued or, in some cases, been dramatically accelerated by DNMs. Yet despite this, DNMs, and the forums which orbit them, undoubtedly provide an innovative ecosystem of harm reduction through vendor transparency, while offering the novelty of complete online anonymity neither of which is possible with real-world illegal drug transactions.

Technological innovations which begin underground often presage or accelerate changes in the wider world. Without digital piracy, for example, we wouldn’t have Netflix, iTunes, or Steam. With DNMs now marking a new frontier in both the evolution of illegal drug markets and the so-called “war on drugs”, we have a choice; continue to abdicate responsibility for harm reduction to the hands of unregulated illegal market actors and organised crime groups, or learn the lessons from these models and bring them out of the shadows, into a legally and responsibly regulated system which puts public health and social equity at the heart of policy…

…Which would you choose?

NB: The term ‘users’ denotes those who use DNMs, like Facebook or Twitter users. The term ‘people who use drugs’ is employed otherwise.

Bibliography

Coulter, M. (2018). ‘Campaign for legal drug-taking rooms in London as figures reveal worst areas for heroin and morphine deaths’. Evening Standard. Available at: https://www.standard.co.uk/news/london/campaign-for-legal-drugtaking-rooms-in-london-as-new-figures-reveal-worst-boroughs-for-heroin-and-morphine-deaths-a3807746.html (Accessed: 21/03/2022).

Davis, J. H. (2017). ‘Trump Declares Opioid Crisis a ‘Health Emergency’ but Requests No Funds’. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/26/us/politics/trump-opioid-crisis.html (Accessed: 03/02/2020).

Hout, M.C.V. & Bingham, T. (2013). ‘‘Surfing the Silk Road’: A study of users’ experiences’. International Journal of Drug Policy. 24: 524 – 529.

Smith, G.E. (2019). ‘It Was All a Dream: The Demise of the Oldest Dark-Net Marketplace’. The SOAS Spirit. Available at: http://soasspirit.co.uk/category/features/page/3/ (Accessed: 17/01/2020).

Smith, G.E. (2020). Citizenship in a Digital Age: The Politicisation of User Experience on the Darknet Marketplace. London: SOAS, University of London.

Transform Drug Policy Foundation (2009). After the War on Drugs: Blueprint for Regulation. Bristol: Adam Shaw Associates.

Trott, D. T. (2019). The Drug Users Bible: Harm Reduction, Risk Mitigation, Personal Safety. UK: MxZero Publishing.