The two key pieces of legislation that establish drug offences in the UK are the 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act and the 2016 Psychoactive Substances Act. In addition, the implementation of this legislation is shaped by further key legislation, such as the Drugs Act 2005. For a full history of UK drug legislation, see our drug policy timeline.

The Misuse of Drugs Act (MDA) brought the UK into line with the UN drug control conventions, while consolidating previous drug laws going back to the 1920s. It defined criminal offences for specified activities including possession, supply and production of ‘controlled drugs’. It also specified which drugs were controlled, through a schedule that mirrored the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. This list can be updated or amended at any time.

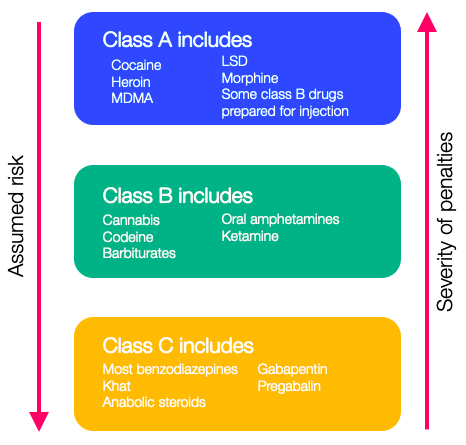

Drugs are classified as Class A, B, or C, according to an assessment of their relative harms (A deemed most harmful, C least). These classifications are coupled to a hierarchy of sanctions, with harsher prison sentences and fines for drugs in higher classifications.

The MDA also set out powers for the police to stop and search individuals for suspicion of drug possession. These powers, contained in s23 of the Act remain some of the most controversial - having led to severe racial disparities in the way they are used.

The Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs

The Misuse of Drugs Act also established an independent expert advisory group, the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD), which is entrusted with monitoring the drug situation in the UK and advising ministers on measures ‘whether or not involving alteration of the law’ to address related social or health problems, including ‘for restricting the availability of such drugs or supervising the arrangements for their supply’. They are also tasked with making recommendations to amend drug classifications, or add new drugs to Class A, B, or C - either at the request of a minister, or when they consider it necessary.

In the years since it was passed, many new drugs have been classified under the MDA, including MDMA (1975), ketamine (2006, moved up to Class B in 2014) and khat (2014). Drugs have also been placed in different classes. Most notably, following recommendations from the ACMD cannabis was reclassified as Class C (from Class B) in 2004. Controversially, however - and in a political decision against the recommendations of the ACMD - it was reclassified as Class B in 2009.

The Psychoactive Substances Act 2016

From the mid-2000s, the rate at which new ‘synthetic’ drugs were being produced began to increase significantly.

These so-called ‘legal highs’ were compounds that were not classified under the MDA - and so could be supplied legally - but that had similar effects to many prohibited drugs. This is how ‘spice’, a synthetic cannabinoid, first appeared in the UK, as well as legal stimulants drugs such as BZP and mephedrone that sought to recreate the effects of MDMA or amphetamine.

Following widespread media coverage, and recognising the difficulty of assessing and classifying increasing numbers of novel drugs at high speed, the UK government introduced the Psychoactive Substances Act in 2016. This took a far broader approach: criminalising the production and sale of any substance which “is capable of producing a psychoactive effect”. Inevitably, this definition also covered commonly used drugs like alcohol, nicotine and caffeine - so the Act contains a list of exempt psychoactive substances, including alcohol and nicotine.

Criminal offences

It is unlawful to supply (including giving away for free), produce, import or export drugs controlled under either Act (although sanctions vary). The Misuse of Drugs Act additionally makes it an offence in itself just to possess a controlled drug, whereas the Psychoactive Substances Act does not (unless the person is in a custodial setting).

The Misuse of Drugs Act also makes it an offence for an occupier to allow their premises to be used for production or supply offences. However it also goes further, making it a specific offence for occupiers to allow the preparation of opium for smoking, or the smoking of cannabis, cannabis resin, or prepared opium, on their property. This has specific implications for the establishment of overdose prevention centres, and continues to be used to block their creation.

If you need help understanding UK drug laws in more detail, our colleagues Release provide detailed overviews on their website and operate a legal helpline for those impacted.