20th October 2015

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime has responded to the ‘leak’ of its briefing paper calling for the decriminalisation of drug possession for personal use. Before considering this response, it’s important to be clear this wasn’t really a ‘leak’ in the classic sense. The document was to be presented by the UNODC at the International Harm Reduction Conference in Kuala Lumpur, and an embargoed copy had already gone to select media (the norm for such publication events). When it was then pulled at the last minute, the BBC, which had already filmed a news segment on it, decided to release it anyway. Richard Branson was filmed for the segment as a member of the Global Commission on Drug Policy, and was sufficiently annoyed when the UNODC backtracked, that he broke the story himself on his blog.

The UNODC response claims that the briefing is not a final or formal document, and does not amount to a statement of its policy position. It also rejects the allegation that the briefing was stopped from being launched as a result of political pressure. This does, however, feel distinctly like an organisation backtracking under pressure (even if that is something, of course, they would never own up to). It would certainly not be the first time member state presssure has led to supression of a controversial UN drugs paper. Its impossible to know what pressure might have been applied, but this report from New York Times at least strongly suggests that it was the US (as widely suspected) that derailed the publication (ironically having found out about it via a New York Times approach for comment).

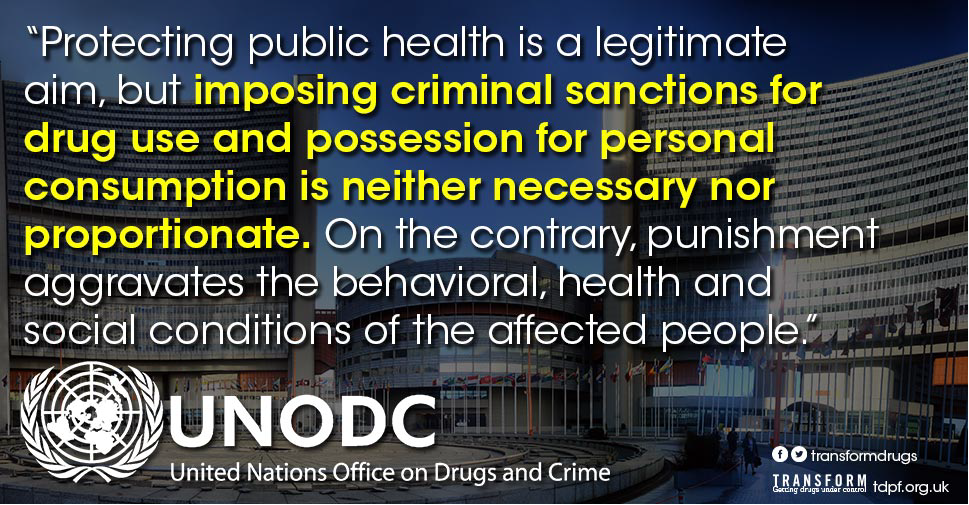

Regarding the UNODC statement on the retraction; firstly, while the agency now says its decriminalisation paper “cannot be read as a statement of UNODC policy”, the paper itself explicitly says “This document clarifies the position of the UNODC”, before going on to deliver its damning critique of criminalisation and its recommendation to decriminalise personal drug possession and low-level drug dealing offences, all carefully referenced to the relevant UN statements, evidence and international law.

Secondly, it is entirely normal for departments within UN agencies (in this case the HIV/AIDS section of UNODC) to provide briefings and guidance on areas within their specific remit. In no way does every utterance from a UN agency require sign off from the director and board. Last year, for example, the World Health Organization recommended the decriminalisation of drug possession deep within a technical report on how to respond to HIV among key populations. Documents like this are quite rightly taken as statements of institutional positions – in the UNODC’s case, the paper’s own introduction sets the document up as clarification and guidance from a UN agency, not merely from an individual consultant or staffer.

Thirdly, to provide some context missing from much of the coverage, this is a guidance paper that has come about following longstanding pressure from, and discussions with, a range of civil society organisations, notably the International Drug Policy Consortium (IDPC), Harm Reduction International (HRI), and the International Network of People who Use Drugs (INPUD). They have demanded the UNODC clarify its position on decriminalisation – especially in light of evolving positions elsewhere in the UN. The UNODC committed to produce such a document almost two years ago. So to somehow suggest this has spontaneously appeared from one rogue staffer without thought or discussion is ludicrous. Contrary to the Telegraph’s reporting of the story, this document has in fact been developed and discussed internally within the UNODC, over a period of more than a year. Monica Beg and the UNODC’s HIV team – who the UNODC media spokesperson in Vienna has rather disgracefully been attempting to scapegoat – are in fact the heroes of the hour for driving this long overdue clarification through to publication.

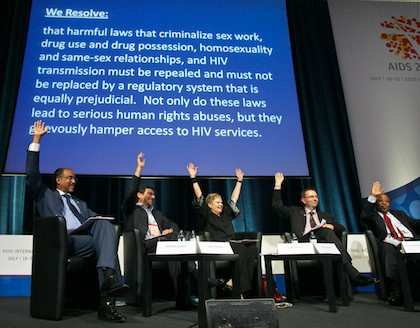

It is also crucial to note that a range of other UN bodies and officials – including UNAIDS, the UN Development Programme, UN Women, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights – have already clearly and publicly stated their support for decriminalisation.

UNAIDS in particular have been openly calling for decriminalisation as part of the HIV response as far back as 2010:

When the WHO followed suit last year (again in the context of the HIV response), with a clear and unambiguous call to decriminalise possession and use offences for all drugs, it was highlighted by civil society, and then by the media, and there were some similarly lame attempts to backtrack. But ultimately the position remained unchallenged.

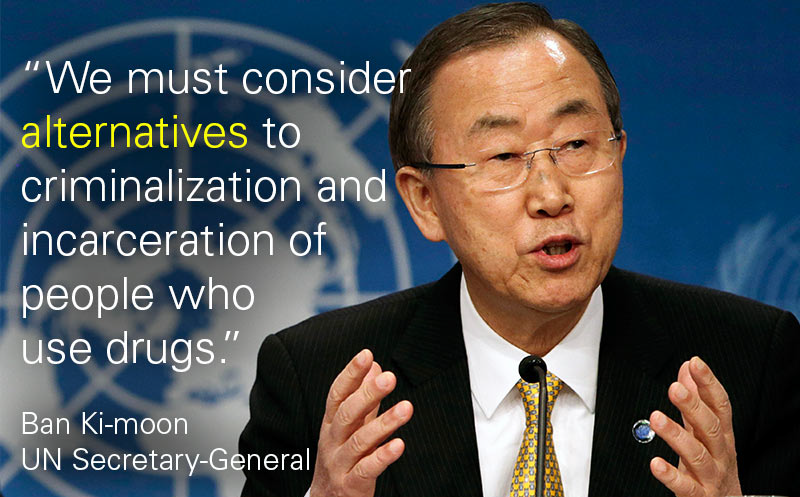

In addition to these agencies, the current UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, the previous Secretary-General Kofi Annan, and the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health have done the same.

So the UNODC’s (non-)announcement is not some radical departure from what the rest of the UN thinks on this issue – in fact, it is more a case of them falling in line with a well established UN position.

Indeed, given the need for ‘system wide coherence’ on policy and legal positions, and related messaging, across UN agencies, it was more a matter of when, not if, the UNODC’s endorsement would emerge. The pressure may have initially come from civil society but that could probably have been deflected, at least for a while longer. But the need to align messaging with the rest of the UN family as next year’s General Assembly Special Session on drugs (UNGASS) approaches will have been all but unavoidable.

So the UNODC has actually been under pressure on this issue for some time within the UN system – even if this drama has been largely playing out behind the scenes. UNODC shares a joint responsibility for the international HIV/AIDS response with UNAIDS and the WHO. As purely health agencies, they are naturally more pragmatic, unencumbered with the punitive prohibitionist ethos that still infuses significant portions of the UNODC (and International Narcotics Control Board). The tensions between the health and human rights pragmatists of other agencies and the anti-reform prohibitionist instincts of the UNODC old-school have been increasingly evident, and the same tensions have also been playing out within the UNODC, with the more forward-looking HIV team attempting to drag a lumbering drug-war monolith into the modern world.

The UNODC statement can be seen as a natural progression – from merely permitting decriminalisation to directing member states to adopt it – when you consider some of the agency’s previous statements in relation to the policy. In the box below, there are some examples of the UNODC suggesting decriminalisation in the past.

- As far back as 2009 the UNODC produced a document called ‘From coercion to cohesion: Treating drug dependence through health care, not punishment’. While this didn’t overtly advocate decriminalisation, it did highlight the costs of some criminal justice approaches and emphasised the evidence supporting treatment-based alternatives to criminalisation.

- In 2013, a UNODC online news feature called ‘Drug policies should be based on health and not on punishment, says UNODC at International Symposium on Drugs’ notes that ‘Referring to the international drug conventions of which UNODC is the guardian, [UNODC spokesperson] Gerra noted that drug users should not be punished or detained...’

- In 2013, a UNODC briefing on Women and HIV stated that: "The criminalization of drug use heavily influences the accessibility of harm reduction services. Similarly, legal frameworks can obstruct the provision of services for all people who inject drugs, such as where police arrest health workers supplying sterile injecting equipment and individuals who possess the equipment. However, some policies, practices or laws have different, and often more profound and debilitating, impacts on women."

- The executive director of the UNODC, Yury Fedotov, said two years ago that people who use drugs should “not [be] treated as criminals, but as patients, in full respect of their human rights".

- A paper the agency prepared for the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights earlier this year makes many of the same human rights-based arguments for reform as the new briefing.

- The UNODC has stated explicitly at the regional dialogues on drug policy and HIV in South Asia and Southeast Asia over the past two months, that the conventions ‘allow/support’ decriminalisation. This is a template presentation to be delivered at each of the 7 regional dialogues. Take a look at slide 4, which covers a number of points explored in the new briefing. (Does this read like something they are opposed to?)

- Just last week, Jeremy Douglas, UNODC Regional Representative for Southeast Asia and the Pacific, gave a speech at the opening of the regional dialogue in Southeast Asia where he calls for a shift from a ‘sanction-oriented to a health-oriented approach to drug use and dependence’ and highlights that ‘it is clear that addressing the legal and policy barriers to accessing essential health services needed by people who use drugs is critical.

These barriers result in people who use drugs facing stigma and discrimination as well as criminalization and punitive policies being an entrenched part of the drug rehabilitation landscape in the region’

Viewed in this context, the road that led the UNODC to its new position is clear. What the document does – rather brilliantly – is compile all the previous analysis and UNODC thinking on this issue, and combine it with the analysis from the other UN agencies. In doing so, it brings together key arguments relating to the criminalisation of drug users and health and HIV, the stigmatisation and discrimination of marginalised populations, human rights law (specifically with regard to the right to health) and development. It’s like a greatest hits compilation of UN expert opinion – and it is this collective force of argument that makes it so devastating.

But if, as the UNODC says, it was merely ‘intended for dissemination and discussion’ at the Kuala Lumpur conference, then why was the document withdrawn at all? Why not release it so that it could be discussed, as it was supposedly meant to be? It all points to an outside intervention.

One might reasonably suspect that the UNODC are privately not too bothered that the document is out – that in fact it is what they wanted, and the half-baked retraction is just bluster to appease an uppity member state that might happen to be a major UNODC funder.

But whatever has gone on behind the scenes, the UNODC are now answerable to a document that is very much in the public domain. If they are suggesting there are flaws in the analysis, or that they don’t agree with any of it, then they will need to say why. They won’t be able to because it’s a legally and empirically bulletproof briefing that largely echoes statements they and other UN agencies have previously made. The UNODC, when challenged, will stand by the content of this document – because they have to.>

They wrote it, and it is 100% correct.