29th January 2019

Dealing with risk is notoriously difficult. How risky is riding a bicycle, eating bacon or climbing a mountain? Experts have tried to devise measures for such things (memorably called ‘micromorts’); however, even when we have good information on risk we usually miscalculate when applying it to our own lives. We over-estimate the risks of things that we see happen more often (often because they are reported in the media), risks that have more extreme outcomes (like plane crashes), or risks that involve activities we don’t like. We also tend to under-estimate the risks of things we enjoy. I happily discount the risks of cycling while probably over-estimating how healthy cycling through rush-hour traffic really is. Like most people, I almost certainly over-estimate the risk of flying, while under-estimating the risk of crossing the road. These are natural human instincts that probably served some useful evolutionary function in the wild; but can be really unhelpful in a complex, modern world where we are making potentially risky decisions all the time, while being bombarded with partial information.

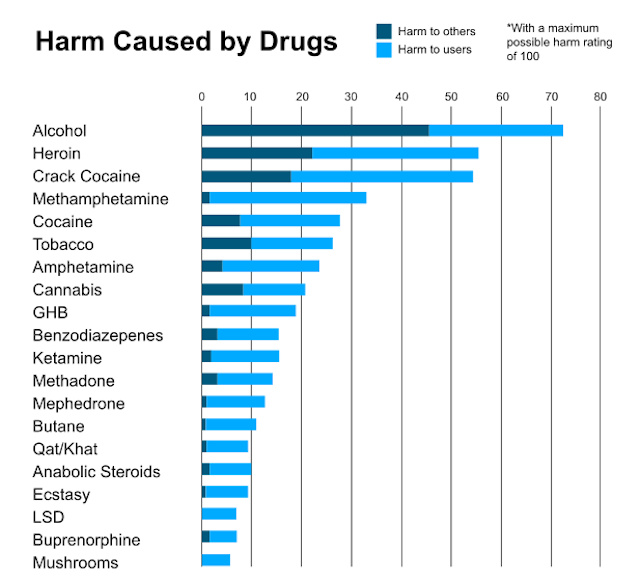

Our problems assessing risk make talking about drug policy especially difficult. In policy debates, the risks of drinking alcohol are often under-estimated while the opposite is true for currently illegal drugs. As David Nutt and others have shown, taken objectively (as far as such things can be) alcohol is one of the most risky psychoactive substances on a range of measures.

Public debates should reflect this, but rarely do. Alcohol and nicotine are legally regulated while most other drugs are not – so we can have a reasonably honest conversation about drinking and alcohol policy, but talking candidly about drug policy is more difficult.

Assessing risk is hugely complex and is an imperfect science. All substance use comes with some level of risk, and it varies by dose, frequency of use, context, physiology and a range of other factors. However, many of those risks are amplified, and certainly added to, by prohibition. Left outside of the law, drug markets are characterised by exploitation, violence, and adulteration. Someone buying, say, ecstasy risks interacting with violent suppliers, consuming a substance of unknown provenance, strength and purity - devoid of content and safety information and, facing a criminal record for possession.

Similarly, for vulnerable young people, who too often get caught up in illegal supply networks such as ‘county lines’, current drug laws create an additional risk of exploitation, violence, criminalisation and prison. In this respect, current laws amplify vulnerabilities rather than reduce them. Added to this are the vast, international networks of exploitation (again, impacting most heavily on the poorest people in the poorest countries) that emerge when a multi-billion pound industry is taken out of all formal control.

Our recent campaign makes this point starkly.

All drugs come with risks, but prohibition makes both supply and use more dangerous and, too often, lethal. If illegal drugs are more closely associated with guns than legal drugs like alcohol, it is not because they make people more violent than alcohol (few substances do); it is because the market is currently unregulated and dominated by people operating outside of the law.

The biggest victims of such a situation are those least able – because of poverty, exclusion or systemic prejudice – to protect themselves. They are also the families bereaved by drugs or harmed though, for example, the imprisonment or intimidation of loved ones - many of whom are now bravely speaking up for reform through our Anyone’s Child campaign for safer drug control. The law, in this respect, amplifies harm where it should seek to reduce it.

Calling for reform is not saying we want a free-for-all, and it’s not ignoring the inherent risks of consumption. It is taking the pragmatic, humane position that since the drug-free utopia promised by prohibition has consistently delivered the exact opposite, the law needs urgently to be changed. Policy can make risky behaviours more dangerous, or it can make them safer. Right now, it does the former; that’s why we want to change it.

James Nicholls, Chief Executive Officer