17th October 2019

This briefing is also available to download as a fully referenced version.

It is now a year since Canada moved to legally regulate cannabis for recreational use, becoming the second country after Uruguay, and the first major G7 economy, to do so (excluding the 11 US states that have now done so outside of US federal jurisdiction). While legal access to cannabis was already available for medical purposes, this marked a groundbreaking policy shift away from criminalisation of the drug and the people who use it in a country of nearly 40 million people.>

The Canadian Government emphasised three key goals of regulation: the protection of public health; the protection of young people; and the reduction in criminality associated with the illegal market. The reforms built on years of evidence demonstrating that the illegal status of cannabis did not prevent rising consumption and was associated with a range of other risks, from increased potency to the empowerment of criminal gangs.

Historically, Canadian provinces have developed separate systems for regulating the sale of alcohol, and a similar devolved principle was applied to cannabis. As a result, a ‘patchwork’ of regulatory models has now emerged across the country. Some provinces have been more successful than others and many have experienced ‘teething’ issues during early implementation. Importantly, the Cannabis Act only allowed for herbal cannabis and oils to be sold in the first year. The sale of cannabis ‘edibles’ and concentrates are subject to separate regulations and are due to go on sale later this year in phase 2 of the implementation.

Establishing an entirely new regulated market – aimed at displacing well-established illegal supply – was a unique challenge. While some have raised concerns that the intensity of cannabis regulation has slowed participation in the new legal market, others remain worried about creeping commercialisation. It will inevitably take time for the new system to bed in and for emerging problems to be addressed. Policy will hopefully evolve as evidence is gathered, and learning is shared across provinces. This briefing reviews the early data since legalisation and considers lessons other countries might draw from the Canadian experience.

Since the beginning of 2018, Statistics Canada has been collating self-reported consumption and purchasing data in the ‘National Cannabis Survey’. This has allowed it to monitor changes in cannabis-related behaviour both before and after legalisation. Previous national survey data showed a long history of high levels of cannabis consumption in Canada. Use has been rising since 2012-13 (4-5 years before the legal market opened) across all age groups, bar a contrasting reduction in use amongst 15-17 year olds.

It is worth noting that survey data includes both medical and recreational users. In the fourth quarter of 2018, just under half of those consuming cannabis reported doing so for recreational purposes only. However, over half of those stating that they used cannabis for purely medical reasons lacked the relevant documentation to purchase cannabis legally, meaning they would still have been accessing the illegal market prior to October 2018.

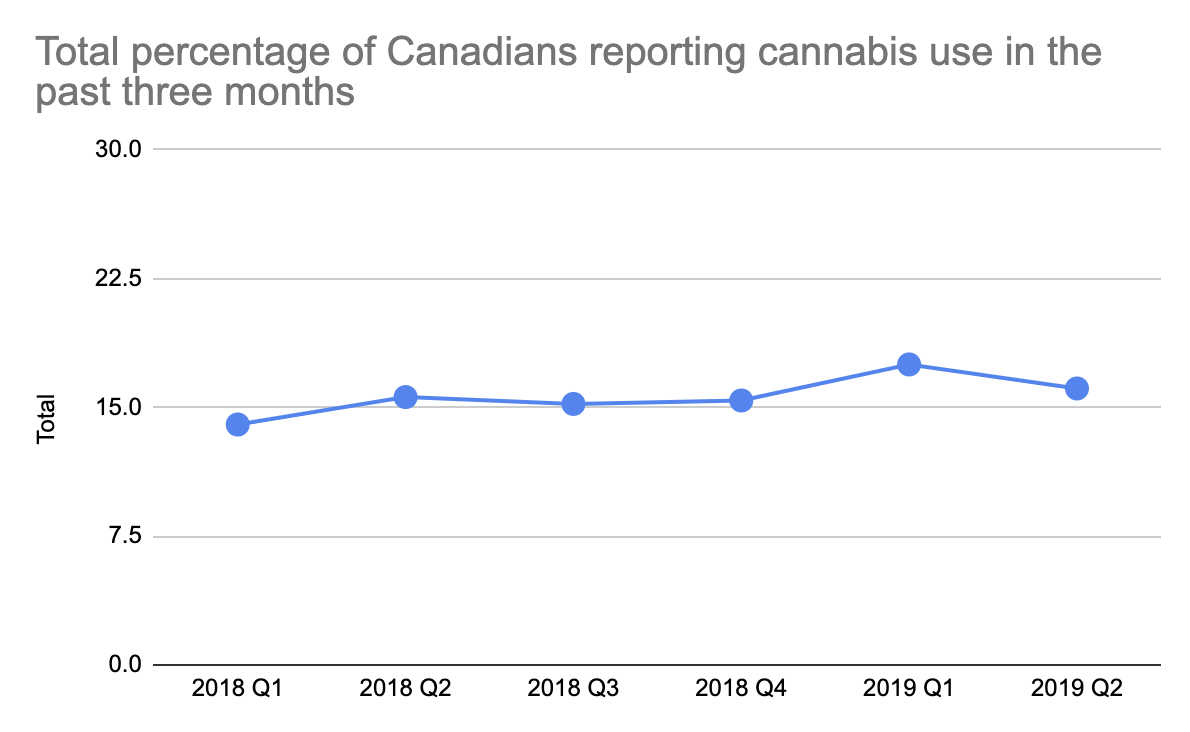

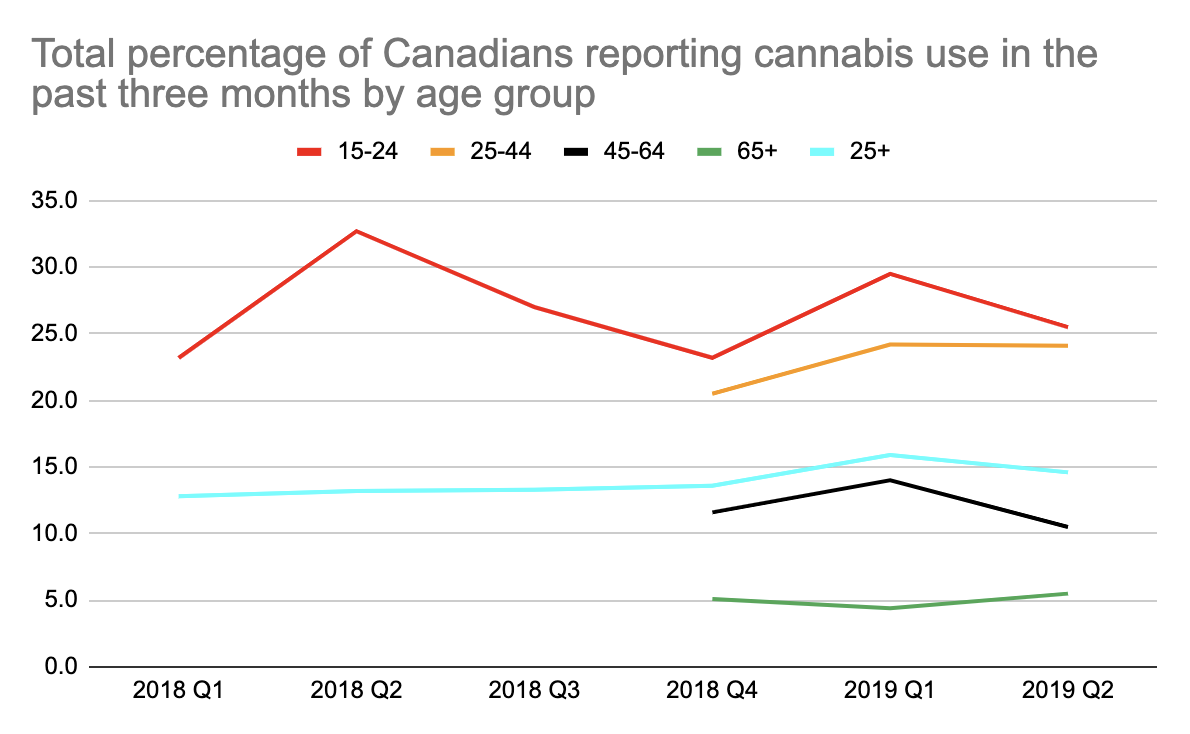

Survey data suggests the prevalence of cannabis use has remained relatively stable since the reform. After a small rise in the first quarter of 2019, reported consumption went back down to pre-October 2018 levels in the second quarter. There is some evidence that those who already consumed cannabis prior to regulation are consuming more. Data from the first quarter of 2019 indicates that the number of occasional users did increase slightly compared to the same quarter in 2018. Those who reported consuming cannabis ‘once or twice’ over the past three months rose from 4.3% to 5.8%, while weekly users rose from 2.4% to 3.6%. This, too, could potentially be linked to a novelty ‘blip’ and changes in survey honesty following the law change. Longer term trend data will no doubt provide a clearer picture.

The National Cannabis Survey recorded an increase in first-time users in the first quarter of 2019, with the number who consumed cannabis for the first time within the past three months doubling from 327,000 in the first quarter of 2018 to 646,000 in the first quarter of 2019. This represented 12% of total users in the same time period but, interestingly, over half of these individuals were aged 45 or older.

This meant that a fifth of cannabis consumers aged 45 or over (331,000 in total) reported using cannabis for the first time at the start of 2019, despite the actual increase in over 45s consuming cannabis as against the previous quarter being relatively small. As discussed below, comparisons of self-reporting data before and after legalisation should be treated cautiously. However, the data suggests that the novelty of newly legal cannabis, and increased ease of availability, encouraged some consumption above previous levels in this age group, at least in the few months following reform.

The observed rise among 15-24 year olds in the first quarter of 2019 as against the previous quarter – which was reported by some commentators as a sign that legalisation was driving up youth use – needs to be viewed in a wider context. Levels of consumption in this age group, in fact, remained lower than the second quarter of 2018, and subsequently fell for the second quarter of this year in line with general consumption. This again highlights the risks of jumping to conclusions from the limited short term data that is available at present.

Given there are only two post-legalisation surveys thus far, it is difficult to draw any final conclusions yet. It will be important to maintain effective data collection and surveillance systems going forward to ensure policy and regulation models can respond effectively to any issues that may arise. It is also important to bear in mind what prevalence data does not tell us. Prevalence data contains only limited information on what or how people are consuming. It is, therefore, an imperfect indicator of health impacts (positive or negative) on a given population. A wider review of health indicators will be required over a longer time period to make a clearer assessment of the policy’s impacts.

A sluggish transition from established illegal market to the new legal market.

Despite a large proportion of Canadians who already consumed cannabis indicating that they would move towards legal sources of supply, in reality change has been slower than many expected or hoped. According to Health Canada, legal sales of dry cannabis were over five times higher in July 2019 than July 2018 (when only medical cannabis was legal). The sales of cannabis oil doubled over the same time. Interestingly, the sales recorded for medical purposes in July 2019 were lower than total sales in July 2018, suggesting that at least some of those who previously relied on documentation to access medical cannabis were now accessing cannabis on the legal recreational market, without needing to disclose documentation.

Determining more precisely what proportion of the market is supplied through the legal market is quite problematic. As noted, self-reporting survey data may be biased against reporting of illegal supply. Furthermore, even prior to legalisation there were numerous retail outlets (both ‘brick and mortar’ and online) that were selling medical cannabis illegally, albeit at least partially tolerated in many cases. This blurred distinction between legal, quasi-legal (informal/tolerated/’grey-market’ dispensaries from the pre-legalisation era, but still in operation), and illegal market created a significant degree of confusion that may have also affected survey responses. And while the scale of legal sales is relatively easy to measure (9,747 kg of dried cannabis and 5,558 litres of cannabis oil were sold in July 2019) estimating the size of the quasi-legal and illegal markets is much harder.

According to the National Cannabis Survey, the percentage of total users reporting that they obtained cannabis from illegal sources fell from 51% to 38% between the first quarters of 2018 and 2019. It is worth noting that the survey covers individuals from age 15, who would not be able to legally purchase cannabis in any province until 18 or 19 owing to age-access restrictions. The reliability of the data in this area has been questioned, particularly as the number of individuals reporting legal purchase prior to regulation would appear to exceed the total number of Canadians registered to purchase medical cannabis at the time. Using the Health Canada data for legal sales, Michael Armstrong at Brock University estimates instead that legal sales of both recreational and medical cannabis make up only around a third of the market.

Migration of cannabis consumers to the legal market has also been notably slower in some areas than others. The patchwork of different provincial regulations models means preparedness and implementations speeds have also varied significantly. Alberta and New Brunswick, for example, recorded four times the amount of legal sales per capita as British Columbia, noted for its ‘sluggish rollout of [legally licensed] retail stores’ as well as the remaining ‘grey market’ sales from the informal dispensary sector. Ontario was also slow to establish a retail market, and opted to allocate licences by lottery – an approach which so far has lead to significant problems including undersupply. Alberta, in comparison, now operates roughly 300 retail stores. The problem of availability has also been compounded by supply bottlenecks in the legal market.

There appears to have been, thus far, insufficient pull factors to encourage many individuals with established supply sources to shift to the legal market. Cannabis also remains considerably cheaper on the illegal market. Based on self-reporting data from the third quarter of 2019, Statistics Canada reported that the average cost of a gram of legal cannabis was $10.23 compared to $5.59 for illegal cannabis. Average legal cannabis prices did in fact decline marginally from the 2nd quarter of 2019 (from $10.65) although the price of illegal cannabis also continued to decline.

It has also been suggested that the slow uptake of legal markets is a consequence of strict marketing controls, which may have limited the ability of legal businesses to tempt consumers away from established and trusted illegal market suppliers. While strict regulations on branding and packaging have been praised from a public health perspective, some commentators have questioned whether, with alcohol advertising so ubiquitous, this has ‘relegated [cannabis] to the sidelines’.

The dynamics of the new market are a consequence of multiple, complex factors – including cultural and economic variables that are largely independent of policy and law. It is difficult to disaggregate the drivers of any changes with certainty. While it is not unreasonable to suggest that increased legal availability and the removal of legal barriers and the stigma of criminal activity may be responsible for some of the initial post-legalisation quarter increase, there are, at the very least, likely to be other parallel factors in play.

The initial novelty of cannabis being legally available, combined with the extensive media coverage and publicity around legalisation may have encouraged some individuals to experiment with recreational use, even if such a novelty is short lived. Another factor may be individuals feeling more comfortable reporting recreational cannabis consumption once it was no longer criminalised. Quantifying this effect is difficult, although comparing prospective and retrospective pre-legalisation surveys in Washington State does suggest such an effect may exist.

Lessons, risks and challenges.

Unfortunately, the social justice and equity components of the Cannabis Act were inadequate, and something of an afterthought in the legalisation process. For example, it failed to address the problem of the many thousands of Canadians who have historical criminal records for selling or possessing cannabis – an activity that is no longer criminal. Post-legalisation, new legislation (Bill C-93) was passed, which sought to expedite and remove cost-barriers from the criminal records suspension process. However, more than 500,000 continue to live with criminal records and the stigma stemming from prior convictions. Bill C-93 was criticised for not providing a fair and effective amnesty as it only provides for criminal record suspensions, so does not amount to full ‘expungement’. In comparison, law reform in California has enabled automatic expungement of past marijuana convictions and an estimated 218,000 individuals are due to benefit as a result. The Canadian Bill itself was only implemented after the ‘tireless advocacy’ of civil society groups. The fact that black and indigenous groups have carried a disproportionately greater burden of criminalisation from repressive drug policies has only added to the sense of injustice related to this failure.

There was also a lack of equity programs in the legislation, such as those established in Massachusetts USA. These seek to ensure that people and communities disproportionately impacted by the enforcement of cannabis prohibition are provided an opportunity, and supported to participate in the legal cannabis industry, as well as ensuring a portion of the revenue generated from legal sales is allocated back into such impacted communities. One expert commented that, ‘It was disappointing to see Canada as a global leader in one regard, but totally miss the mark on ...social justice measures’.

The Canadian approach has also been criticised for creating barriers to entry for smaller enterprises, thereby favouring the larger corporate actors who now dominate the market. The Cannabis Act introduced a variety of cannabis licensing classes, including ‘micro-cultivation’, which was hoped to open the market to smaller producers. However, the federal government announced earlier this year that, in order to apply for a licence, the potential supplier must already have a production facility in place, meaning those unable to risk the initial investment are immediately deterred from applying. This has contributed to an emerging market dominated by a relatively small number of large corporate actors, in turn fueling the risk of monopolisation. The dynamics of corporate capture and related distortions of the policymaking process (of the kind seen especially in the alcohol and tobacco industry) are a significant and pressing concern, and one that has not been diminished by significant investment from alcohol and tobacco corporations in the Canadian cannabis sector.

Further afield, the emergence of multi-billion dollar cannabis corporations has led to accusations of predatory activities in emerging cannabis markets in low and middle income countries. In Colombia, for example, Canadian companies currently represent 85% of total investment in the emerging medical cannabis market. Local farmers have expressed concerns about both environmental impacts and being marginalised from decision making. Canadian venture capital has been similarly prominent in emerging cannabis markets in Mexico, Jamaica, Lesotho and elsewhere. While this is not a failure of Canadian legislation per se (and Canadian corporate exploitation of developing economies – for example in the mining sector – is nothing new), it does raise important questions for the international community about how future markets should be structured, how traditional cannabis growing communities can be protected, and how fair trade and sustainable development can be guaranteed.

There is certainly space for learning. As the first G7 economy to legalise and regulate cannabis, Canada entered uncharted territory. It also did so guided by public health principles and with a strong commitment to evidence-based policy development. On that principle, Canada, and the growing list of countries seeking to follow their example, should learn from both the successes and failings – at federal, provincial, and municipal levels – and ensure policy continues to evolve in a positive direction. Effective monitoring and sharing of experiences and best practice between the different tiers of government domestically, and between Canada and other reform minded jurisdictions, will remain an essential part of effective policy making moving forward.