18th November 2019

Funding Heroin Assisted Treatment through increased Proceeds of Crime Act Money

This briefing is also available in PDF format.

Our approach to heroin and crack markets cannot continue as it is. According to PHE1, global opium production increased by 65% in 2017 to a record high, and global cocaine production rose 56% from 2013-16, contributing to crack cocaine purity doubling, and use rising. Seizures in this environment are a cost of doing business for Organised Crime Groups (OCGs). To reduce the scale of the market and its negative impacts, we must reduce demand for illegal drugs.

That is why a number of PCCs and senior police officers are calling for pump-priming funding to pilot new Heroin Assisted Treatment (HAT) clinics to reduce the use of illegal heroin, and to evaluate their impact on health, crime and OCGs. Priority locations could include the five Heroin and Crack Cocaine Action Areas identified under the 2018 Serious Violence Strategy.

HAT involves prescribing heroin for supervised use in a clinic to people for whom other treatments have not worked (or for take-home use where appropriate). It substantially reduces consumption of illegal heroin, acquisitive crime to fund use, discarded needles and health problems including overdoses, deaths and HIV infections from needle sharing. It increases take-up and retention in treatment, and has a long history, including successful UK trials.2 It is recommended in the Government’s Modern Crime Prevention Strategy.3 The Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs has called for HAT to be funded by the Government. 4

Funding through Proceeds of Crime Act (POCA) money

Many drug treatment services have seen large cuts in funding, and cannot meet existing demand. So to fund HAT from the treatment budget would require cutting other drug services - wiping out any benefits. So instead, pilots could be partly funded by temporarily increasing the proportion of money police get from Financial Investigations and under the Proceeds of Crime Act - currently 18.5% of money from confiscation orders, or 50% of cash seizures (see 'POCA and Financial Investigations' below).

So money taken from those who profit most from the illegal drugs trade - OCGs - would be used to deprive OCGs of part of the drugs market, while helping vulnerable individuals and communities harmed as a result their activities. It is important that the focus is on serious criminals, not small suppliers who are only involved because they are themselves dependent on heroin. HAT would not only reduce demand on the police, but on the CPS and the courts, which would help offset any reduction in money they received from POCA funds. Other stakeholders also set to benefit from reduced demands on their services (such as CCGs, local authorities, Community Rehabilitation Companies, prisons, businesses, etc.) could then contribute any additional funding required.

POCA and Financial Investigations

A confiscation order is a post-conviction court order, which is value-based rather than asset-based. It does not confiscate property, but is an order to repay the value of the benefit the criminal has obtained as a result of the offence or lifestyle. A confiscation order is split as follows:

- 50% of the value is retained by the Treasury

- 18.75% investigation agencies (Police and Crime Commissioners)

- 18.75% prosecution (Crown Prosecution Services)

- 12.5% enforcement agencies (HM Courts & Tribunal Service)

Another tool available is cash forfeiture. Only 50% is retained by police forces, the other 50% goes to the Treasury.

Why is HAT important for policing?

Disempowering OCGs by taking their customers away

In Switzerland, where HAT has been used since 1994, research suggests that the 10-15% of people eligible for HAT use 30-60% of all illegal heroin.5 This is in line with other drug use patterns e.g. the 4% heaviest drinkers in the UK provide 23% of alcohol industry revenue, and the 25% heaviest some 68% of revenue.6 Taking this very high-using segment of their customer base away could significantly reduce OCG income from the drugs market.

Reducing demand for illegal heroin

The UK trials of HAT found three quarters of those prescribed heroin substantially reduced use of ‘street’ heroin.7 Of these, three quarters remained almost, or completely abstinent. This is remarkable in a group for whom daily illicit use - even while in treatment - was the norm.

Clients were spending an average of just over £300 a week on illegal drugs before entering the UK trial. This reduced to under £50 a week at 6 months. If replicated, 50 people in HAT could reduce illegal heroin revenue by £650k per year in an area. In Switzerland about 6% of the heroin using population is in HAT at any given point. Extrapolating from the UK trial numbers, getting 6% of our ~300k people dependent on heroin into HAT would equate to £4.5m of revenue taken from the illegal market every week, or £234 million a year.8 Anecdotal evidence from police and treatment staff suggests that £300 per week spent on drugs may well be conservative, so the impact could be even greater.

Swiss research concluded: “It seems likely that users who were admitted to the program accounted for a substantial proportion of consumption of illicit heroin, and that removing them from the illicit market has damaged the market’s viability.”9

Reducing number of small-time dealers, and new people using heroin.

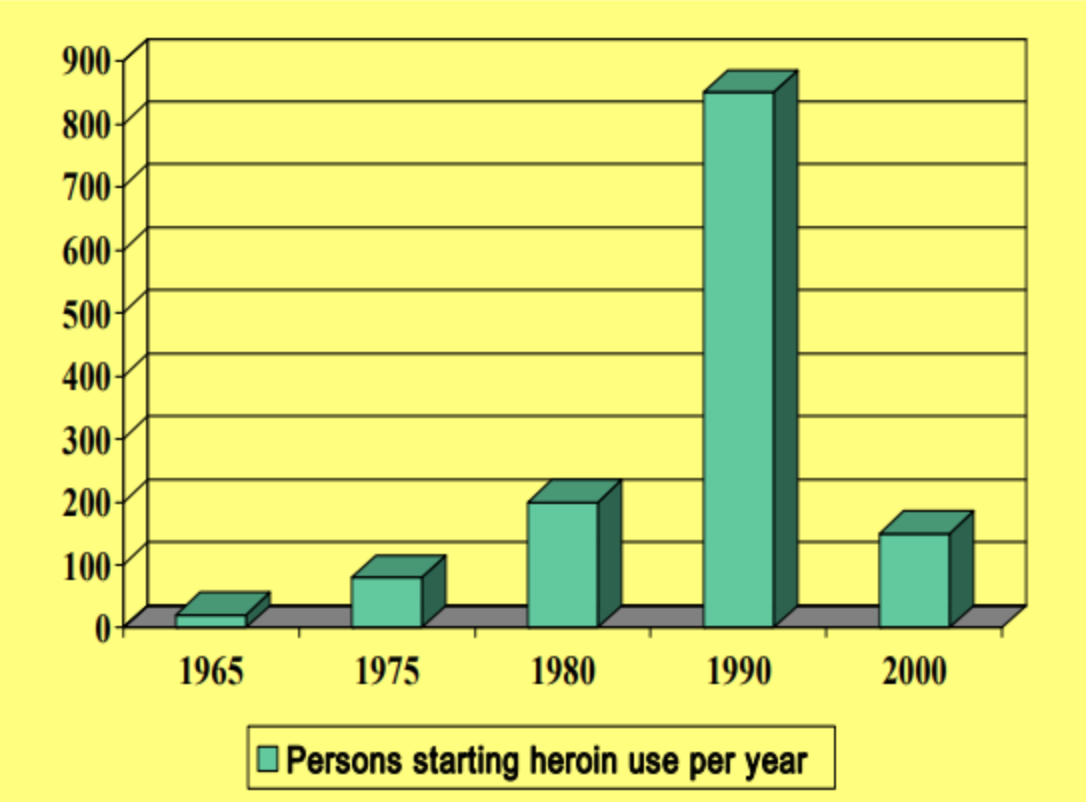

In Swiss trials, 43% of patients entering HAT sold drugs to finance their own use. This fell to 6% after 12 months, a figure confirmed by police data showing an 80% fall in the number of offences participants committed after 24 months. The researchers said that it is likely the programme disrupted the functioning of the market by removing retail workers. “The workers no longer sold drugs to existing users, and equally important, no longer recruited new users into the market. The heroin prescription market may thus have had a significant impact on heroin markets in Switzerland.”10 With researchers also concluding that; “The harm reduction policy of Switzerland and its emphasis on the medicalisation of the heroin problem seems to have contributed to the image of heroin as unattractive for young people.”11 For example, following the introduction of a harm reduction approach including HAT in the early 1990s, the number of new people using heroin in the Zurich area fell from 850 per year to 150 (see graph), and the population of problematic heroin users declined by 4% a year.12

Graph: Incidence of new people using heroin in the Zurich Canton of Switzerland.13

Reducing demand for crack

A recent PHE report on increasing levels of crack use, and the violence around the crack market, highlighted the need to: “explore more effective methods of getting crack users into treatment and to provide a more attractive treatment offer which is tailored to their specific needs.”14

The primary drug that most people who use crack are dependent on is heroin. As PHE says; “[P]eople starting crack treatment...tended to be established heroin users”.15 But for those who have tried existing treatments and found they don’t work, entering HAT provides an opportunity to address both their heroin and crack use at the same time.

For example, prior to entering the UK HAT trials, around three quarters of the group were using crack, while at 6 months this proportion had reduced, as had the amount used.16 In Switzerland, research found only 15% of new HAT clients had not used crack/cocaine in the previous six months; but the proportion of non-cocaine users increased progressively to 28% six months after admission, 35% after 12 months, and 41% after 18 months.17 Dr Thilo Beck, who runs Swiss HAT clinics, explains that: “HAT is a very effective way to get a population that is otherwise difficult to reach into regular treatment. Once in treatment...marked psycho-bio-social stabilisation occurs. In this context reduction/better control of use of other substances like cocaine is frequently seen.”18

Reducing acquisitive crime

Reducing use of illegal drugs reduces the pressure to commit crime to pay for them. For example, the 40 people prescribed heroin in the UK HAT trials were committing 1731 crimes in the 30 days prior to entering treatment. After 6 months, this fell to 547 crimes - a two-thirds reduction. A substantial number became ‘crime-abstinent’. Evaluations in other countries have shown the same result. For example Switzerland saw: “a substantial fall in criminal involvement... This fall was greatest (50% to 90%) for the most serious offenses, such as burglary, muggings, robbery and drug trafficking.” As noted below, this is the driver for the Cleveland PCC to play a major role in funding and developing the HAT clinic in Middlesbrough, which opened in October 2019.

A report on the impact on crime of the UK trial found: “Initially, the police thought that a whole cohort of criminals had either died or migrated away from the area because there were people they had seen on a very regular basis – apprehending them for crimes – and suddenly they weren’t on the police radar at all. Because the heroin-assisted treatment was so effective for them in reducing their criminal activity to fund their habit.”

And; “In Switzerland, one interviewee reported that instances of criminality within the patient group at his HAT clinic had fallen to almost zero. Another reported that the drop in crime has deepened support for the program from police, who generally have a cooperative relationship with clinics”19

County Lines

Taking a substantial part of the illicit heroin market from OCGs that run county lines in and out of large towns and cities would be a major blow to their profits and power. However, while the National Crime Agency says heroin is the most frequently supplied drug via county lines, it should be noted that HAT clinics would not necessarily be viable for towns with small populations. Longer term, expanding take-home HAT (as several hundred people already get in the UK) should also be explored.

Cost Effectiveness

Numerous studies show HAT is cost-effective. For example, research by Glasgow NHS found a HAT clinic could save the public purse more than £940,000 annually in reduced health and social costs.20 As a result, Glasgow NHS will open a pilot clinic in late 2019.

Cleveland PCC Barry Coppinger said in support of HAT: “a prolific cohort of 20 drug-dependent offenders have cost the public purse almost £800,000 over the last two years - and that’s only based on crimes that are detected.”21

Cleveland is exceptional in having found the money for an initial small HAT clinic, with the PCC playing a key role. But most areas will require pump-priming money for a pilot. Given a reduction in crime resulting from HAT would not just reduce demand on police, but on the CPS and court system as well, it is reasonable for both to contribute part of their POCA money to help pilot these schemes. The Government should also contribute part of the money currently being retained by the Treasury.

Budget Needed

The budget needed to open a pilot will vary depending on a number of factors. Historically, the cost of clinical-grade heroin was £12-15k per person, but that has been reduced to about £4250 - around twice the cost of buprenorphine. The bulk of the remaining cost is staffing. This cost can be minimised if an existing facility is used, reducing costs for premises, admin and other overheads. Cleveland’s HAT is estimated to be costing around £12k per person annually - far lower than the potential social and health savings.

Recommendations

PCCs should express support for Heroin Assisted Treatment, include it in their Police and Crime Plans, and call for an increase in POCA money going to police forces to fund HAT pilots. They should also play a convening role in their areas to build support for this call from other criminal justice, public, business and third sector groups. These calls should be made directly to the Home Office, and through the Association of Police and Crime Commissioners.

Senior police officers should also back HAT, and call on the National Police Chiefs’ Council to press the Home Office to increase POCA money to fund it.

Image: Heroin Assisted Treatment Facility in Middlesbrough, UK.

References

- Increase in crack cocaine use inquiry: summary of findings (25 March 2019) https://www.gov.uk/government/...

- Untreatable or just hard to treat? Results of the Randomised Injectable Opioid Treatment Trial (RIOTT) http://fileserver.idpc.net/lib...

- Home Office (2016) Modern Crime Prevention Strategy p30 https://assets.publishing.serv...

- Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (2016), Reducing Opioid-Related Deaths in the UK https://assets.publishing.serv...

- Killias, M. and Aebi, M. (2000) ‘The impact of heroin prescription on heroin markets in Switzerland’, Crime Prevention Studies, vol. 11, pp. 83-99

- Aveek Bhattacharya et al, (2018) How dependent is the alcohol industry on heavy drinking in England? https://onlinelibrary.wiley.co...

- Untreatable or just hard to treat? Results of the Randomised Injectable Opioid Treatment Trial (RIOTT) http://fileserver.idpc.net/lib...

- 6% of approx 300k UK opiate users = 18k. 18,000 x £250 x 52 weeks = £234m

- Killias, M. and Aebi, M. (2000) ‘The impact of heroin prescription on heroin markets in Switzerland’, Crime Prevention Studies, vol. 11, pp. 83-99

- Ibid

- Carlos N, Stohler R, ‘Incidence of heroin use in Zurich, Switzerland: a treatment case register analysis’ (June 03, 2006) https://www.thelancet.com/jour...

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Increase in crack cocaine use inquiry: summary of findings (25 March 2019) https://www.gov.uk/government/...

- Home Office and PHE, ‘Increase in crack cocaine use inquiry: summary of findings’ 25 March 2019 https://www.gov.uk/government/...

- Untreatable or just hard to treat? Results of the Randomised Injectable Opioid Treatment Trial (RIOTT) http://fileserver.idpc.net/lib...

- Killias, M. and Aebi, M. (2000) ‘The impact of heroin prescription on heroin markets in Switzerland’, Crime Prevention Studies, vol. 11, pp. 83-99

- Personal communication to Transform available on request

- Heroin-Assisted Treatment and Supervised Drug Consumption Sites Experience from Four Countries p25 https://www.rand.org/content/d...

- ‘Update on proposed safer drug consumption facility and heroin assisted treatment in Glasgow.’ Friday, June 9, 2017 https://www.nhsggc.org.uk/about-us/media-centre/news/2017/06/proposed-sdcf-and-hat/#

- ‘PCC Updates the Home Secretary on plans for heroin assisted treatment’ https://www.cleveland.pcc.poli...