14th September 2020

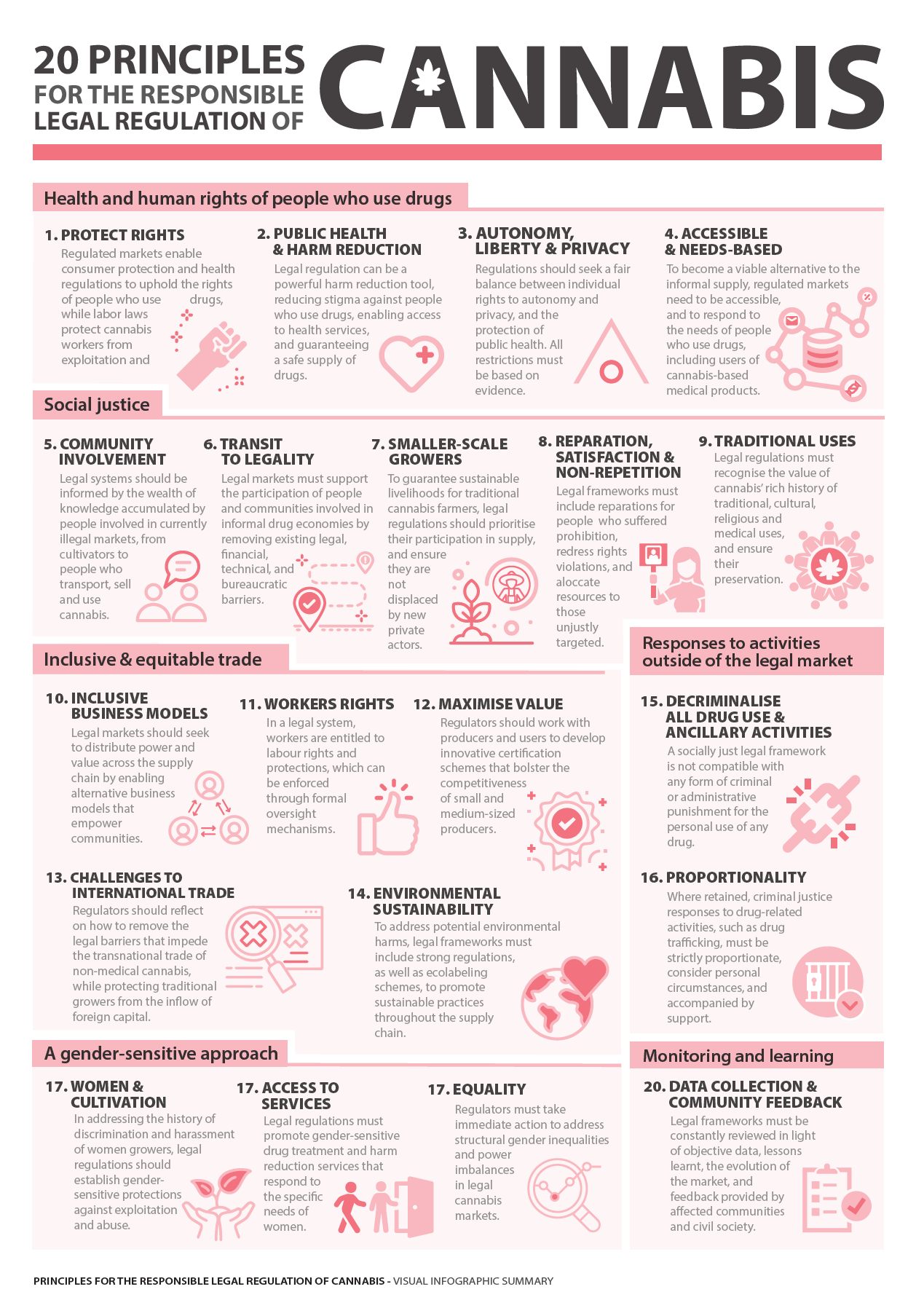

This week, the International Drug Policy Consortium released a new report — with input from its global membership — on principles for the responsible legal regulation of cannabis. The report is essential reading, setting out 20 core principles that should underpin a legal cannabis market, covering health and human rights, social justice, trade, and gender.

Why does this matter at the moment? As cannabis is legally regulated in ever more countries, shouldn’t the focus be increasing the momentum and celebrating success?

It matters enormously that the global consensus on drug policy is fracturing. The needless and damaging criminalisation of cannabis use is being worn away, opening the door to a sensible debate on wider reform.

However, getting it done is not the same as getting it right — and values are paramount. As Kassandra Frederique said on this site recently, drug policy reform is not an end in itself. It is (or should be) a means to creating a fairer and more just society. Therefore, as legally regulated markets emerge we need to ask ourselves: who is set to benefit?

The regulation of drug markets should, at the very least, lessen the burden of criminalisation, particularly on the poor and marginalised communities. But do newly regulated markets reduce social injustice? Do they create greater economic opportunities for marginalised populations? Do they allow those who have suffered the brunt of prohibition to have a stake in the new economy?

In reality, this is not always the case. We have seen a huge degree of corporate capture in the few short years since cannabis has been made legal, especially in the US and Canada. Too often, existing suppliers have been sidelined as corporate entities take over the trade — or, worse, have continued to be criminalised. Too many producers — mostly poor farmers — have been squeezed out of the market due to licensing systems that make it far too expensive to get a toehold and global corporates seeking to dominate local production.

Cynics may ask ‘What did you expect?’. When you create a legal market, corporate interests will do what they always do: seek profits and market share above all else. Just look at tobacco and alcohol. That is a reasonable challenge: no-one wants to repeat the mistakes of previous approaches to legal drugs. But a regulated market is not, and should not be, a free-for-all. Good regulation needs to promote public health, human rights and social justice. As a recent report by Transform and St George’s House shows: this means being both values-driven and alive to the technicalities involved in making those goals a reality.

Effective regulation should promote equity: through licensing systems that facilitate smaller producers and retailers; international trading rules that protect fair trade; legal frameworks that ensure new markets don’t come at the cost of further criminalisation. Critically, these principles need to be hardwired into legislation from the start.

As the case for continuing the drug war weakens, so the debate has to shift. Yes, it is vital to show how, and why, prohibition has damaged individuals, families and communities; but we also need to focus on ensuring that what comes next is just and equitable. By focusing on both values and the details of how future regulation should look, we can end the war and win the peace.

James Nicholls

Chief Executive Officer