12th August 2025

The Changing Landscape of Ketamine Use in the UK

Ketamine is a dissociative anaesthetic originally developed in the 1960s, widely used in both human and veterinary medicine. It remains an important clinical tool and is listed on the World Health Organization’s Model List of Essential Medicines due to its utility in surgery and emergency settings, especially in low-resource environments (ketamine does not depress respiration, to the extent of other sedatives such as benzodiazepines or opioids)

In addition to its medical uses, ketamine produces dose-dependent psychoactive effects. Often categorised as a hallucinogen and/or psychedelic, ketamine’s effects are quite distinct from classic psychedelics like LSD, Psilocybin and DMT. At sub-anaesthetic doses, recreational users often report pleasurable psychedelic-like altered perceptions of time, space, and visual distortions, which at higher doses can escalate into a more distinct, dissociative, out-of-body or ‘k-hole’ experience.

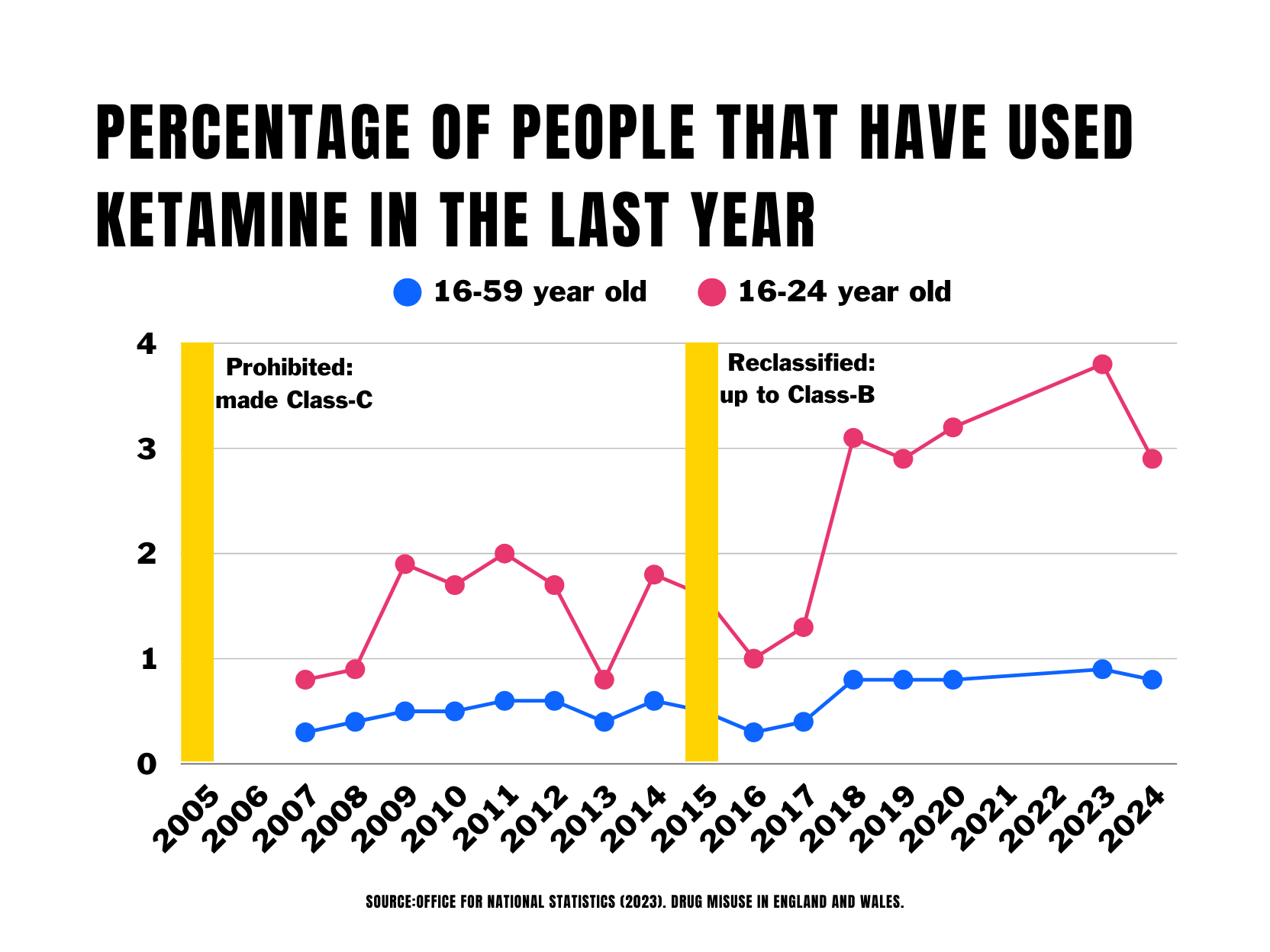

In the UK, it was initially classified as a Class C controlled substance under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 in 2005, reflecting growing concerns over increasing non-medical use. Before 2005 it was nominally legal to possess, but as a prescription-only medicine it was still controlled under the Medicines Act 1968 - so remained illegal to sell. In 2014, in response to emerging evidence of health harms, it was reclassified up to Class B under the Misuse of Drugs Act following a review by the Advisory Council on The Misuse of Drugs (requested by the Government in 2012). Concerns focused on new evidence of potential for bladder/urinary tract damage, and dependence associated with heavy use.

Before the early 2000s, recreational ketamine use in the UK was relatively niche, mostly confined to specific psychedelic and rave scene subcultures. However, in the past two decades, the drug has seen a significant shift into mainstream UK drug culture, particularly among young people and in party/nightlife environments.

Several factors may have contributed to the growing popularity of ketamine:

In the context of a growing cost of living crisis, especially for young people, ketamine is comparatively cheap. Commonly available for £10 - £20 a gram (often less, especially if bought in larger quantities - with some reports of £5 grams) ketamine is far cheaper than, for example, cocaine (£50-£100 a gram). Sharing a gram of ketamine amongst a group of peers, a night of ketamine use will cost an individual less than a single pub-bought alcoholic drink.

Ketamine’s effects, although intense at higher doses, are, like cocaine, relatively short-acting (less than 2 hours when snorted, generally around 45 minutes), and perceived as more manageable compared to longer acting drugs such as MDMA, LSD, Magic Mushrooms, or indeed alcohol.

In recent years ketamine has also achieved a much higher public profile for its therapeutic use, specifically for treatment of depression and other mental health conditions - including a number of celebrity users and endorsements. Its status as a prescription drug has given it a headstart, regarding research and availability, over other ‘psychedelic’ therapies.

The increase in use over the past two decades has been paralleled by a rise in higher risk, more problematic patterns of use. While most users report infrequent, socially bounded consumption, a growing subset are engaging in heavy or daily use, often leading to more serious physical and psychological health complications. These risks are often poorly understood by people using ketamine.

Frequent users often report increasing tolerance, needing increasing doses to achieve the same effects, which can escalate both the dosage and frequency of use, increasing dependency and other risks.

Among the most well-documented risks are severe urological complications. Ketamine-induced ulcerative cystitis and other forms of urinary tract damage, including bladder shrinkage and kidney impairment, are increasingly reported in clinical settings, particularly among young people with long-term, high-frequency use. There is an urgent need for better information to be available to people who use ketamine about these risks - that if not identified early can result in irreversible damage, including loss of the bladder.

Ketamine use has also been associated with a number of fatalities, distinguishing it from other classic psychedelics such as psilocybin or LSD, which have much lower toxicity and limited evidence of direct lethality. Most of these deaths involve polydrug use or accidents during intoxication related to its anaesthetic effects, underscoring the unpredictable and risky nature of high-dose or uncontrolled ketamine use, and risks of use with other drugs - notably including alcohol.

Despite the rise in high risk use, and better understanding of the links between using behaviours and specific harms, the UK currently has an underdeveloped treatment response to problematic ketamine use. Unlike opioids, tobacco and alcohol, for which there are well established treatment pathways, harm reduction services, and pharmacological interventions, individuals with ketamine dependency or related health issues often face limited options for care and support.

Critique of the UK Government’s Proposal to Reclassify Ketamine as a Class-A Drug

In January 2025, the UK Government proposed reclassifying ketamine from a Class B to a Class A drug, citing rising levels of use and associated health harms - requesting the ACMD undertake a review. Reclassification would raise the maximum penalty for possession from 5 to 7 years in prison. The maximum sentence for supply would be raised from 14 years to life, putting it on a par with maximum penalties for murder, rape and genocide.

However, while legitimate concerns over the growing prevalence of problematic ketamine use point to a need for new policy-thinking and reform, the proposed escalation in legal penalties follows a familiar pattern of politically-driven responses, rather than evidence-based policy.

In the past, when ACMD recommendations have not been aligned with the Government’s political priorities (for example with banning under the MDA of khat in 2014, and Nitrous Oxide in 2023, or the reclassification of cannabis from C back to B in 2009) the Government has simply ignored its own experts and made the change anyway. Often (as with cannabis and N2O, and now apparently again with ketamine) the Government has prejudiced the nominally independent review process by making clear its desired outcome in advance or, worse, stating that it would make the change regardless of the recommendations, before the ACMD has reported back.

More than 50 years after becoming law there are no systems or metrics established by the Home Office or ACMD, for evaluating classification/reclassification impacts (on stated goals like deterrence, availability, and health and social harms). There has never been a formal impact assessment of the Misuse of Drugs Act (Transform undertook a review on it 50th anniversary in 2021). There are no published evaluations of previous classifications /reclassifications to inform the upcoming review, notably regarding the 2005 classification of ketamine as Class C under the MDA, or its 2014 reclassification from Class C to B.

The available UK and international evidence, however, consistently shows that increasing criminal penalties does not significantly deter drug use, and reducing penalties does not encourage use either. Harshness of punitive sanctions appears to be, at best, a marginal factor in drug-taking decisions for young people - with personal health risk management, social, cultural and economic variables being the key drivers.

There is no compelling evidence to suggest raising ketamine to Class A status would deter use, or impact availability. Notably, ketamine use went up when it was initially prohibited and made class C under the MDA 1971 (use more than doubled amongst young people in the following 4 years), and rose again after it was reclassified upwards to class B (use amongst young people more than doubled again to the most recent 2024 data). While this is not to suggest that the classification/ reclassification was itself a factor in driving up use, it can certainly be concluded that increasing punishments failed to prevent the dramatic 300+% rise in use since it was initially prohibited.

For additional context, is it useful to consider drugs that occupy a similar cultural niche. The use of cocaine, for example, has been rising consistently over the past decade. During this time purity has risen, whilst prices have fallen. Cocaine-related deaths have risen from 11 in 1993, to over 1100 in 2023. Cocaine has been Class A throughout this period.

Similarly, between 1988 and 1990, MDMA/ecstasy use spiked from near zero to millions of pills being consumed every month. It was also Class A throughout this period - and its popularity and availability has remained resilient to this day despite its Class A status.

Not only does increasing punitive sanctions not appear to have significant impacts on deterrence, or supply and availability, but young people seem more likely to look at classification as a quality guide, than a risk guide.

More concerning is the substantive evidence that harsher criminalisation and enforcement can actively worsen health and social outcomes:

Increasing the threat of punishment for possession is likely to deter or delay people who use ketamine from seeking emergency medical help (increasing the risks of harm/death) and engaging with drug treatment and harm reduction services. This is particularly the case for young people and other marginalised groups for whom such support is most urgently needed, but least accessible.

Criminalisation itself is a public health harm. A criminal record has serious long-term consequences for life chances; fueling stigma and compounding vulnerability, undermining relationships with family and community, and limiting future employment, education, and housing opportunities - all of which are known to be protective factors regarding problematic drug use and criminality.

The increased burden of criminalisation following reclassification will disproportionately fall on marginalised/vulnerable populations, including people with mental health conditions, youth - particularly those with histories of adverse childhood experiences and/or living in care, people experiencing homelessness, the LGBTQ community, people living in poverty, and people from ethnic minorities; groups already overrepresented in the criminal justice system.

Fear of punitive consequences may alienate these key audiences from accessing or engaging with prevention or harm reduction information and engaging in safer use practices.

An increased emphasis on discredited and counterproductive punitive enforcement diverts valuable public resources away from proven health interventions, such as specialist ketamine treatment services, mental health support, prevention and harm-reduction education.

There should be no doubt that the proposed reclassification of ketamine is likely to undermine the health and wellbeing of the very people it is supposed to protect

The well documented harms of punitive enforcement, particularly where targeting vulnerable populations, are precisely why the entire UN system (including the WHO, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, UNICEF, UNAIDS, and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime) actively oppose increased criminalisation, and proactively call upon member states to decriminalise of possession and use of ALL drugs.

The WHO specifically describes decriminalisation as a ‘critical enabler’ of effective public health responses to the challenges of drugs. In the UK the Faculty of Public Health, the Royal Society for Public Health, the Royal College of Medicine, the Royal College of Physicians, The BMJ and the Lancet - and many other authoritative voices in the health field - have similarly all called for decriminalisation of all drug possession and use.

Even the ACMD, now tasked with making the recommendation to increase the classification of ketamine, has (like the Home Office in 2014) previously concluded that there was ‘little consistent international evidence that the criminalisation for possession of drugs for personal use is effective in reducing drug use’, and identified the harms of criminalisation. The ACMD have, more than once, recommended non-criminal sanctions for all drug possession offences.

Non punitive sanctions are not policy concepts alien to the Government. When the Psychoactive Substances Act was passed into law in 2016, it legislated a no sanction model for possession offenses of drugs within its ambit - in other words a decriminalisation model. This was developed for the same reasons the WHO, ACMD, Royal Colleges etc. have long-called for a no-sanction model for possession of drugs more broadly. Kier Starmer (UK Prime Minister), Yvette Cooper (UK Home Secretary) and Diane Johnson (drugs minister) all voted in favour of the Psychoactive Substances Bill containing these no-sanction provisions when it passed into law in 2016.

Criminalising consensual adult risk behaviours is unethical and counterproductive. Increasing the harshness of criminalisation only makes it more so. While ketamine’s rising harms warrant serious attention, reclassifying it as a Class A drug risks repeating past mistakes by prioritising punitive posturing over effective health interventions.

Better ways forward?

The UK should pursue a public health-led strategy grounded in early intervention, targeted prevention, harm reduction education, and access to tailored treatment and social support. These are approaches that, unlike increased criminalisation, are supported by expert opinion, research evidence and international best practice.

ACMD classification reviews have always made important and welcome recommendations for improvements to public health responses to drugs, alongside any recommendations on classification. Somewhat counterintuitively, such harm reduction recommendations have been made even where the increased criminalisation that inevitably accompanies upward reclassifications (which the reviews usually recommend) will itself increase health and social harms.

Key elements of a public health approach, in the short term, must include:

Development, implementation and funding for improved ketamine treatment modalities and training for relevant service providers - with specific focus on urinary tract/bladder issues and dependency.

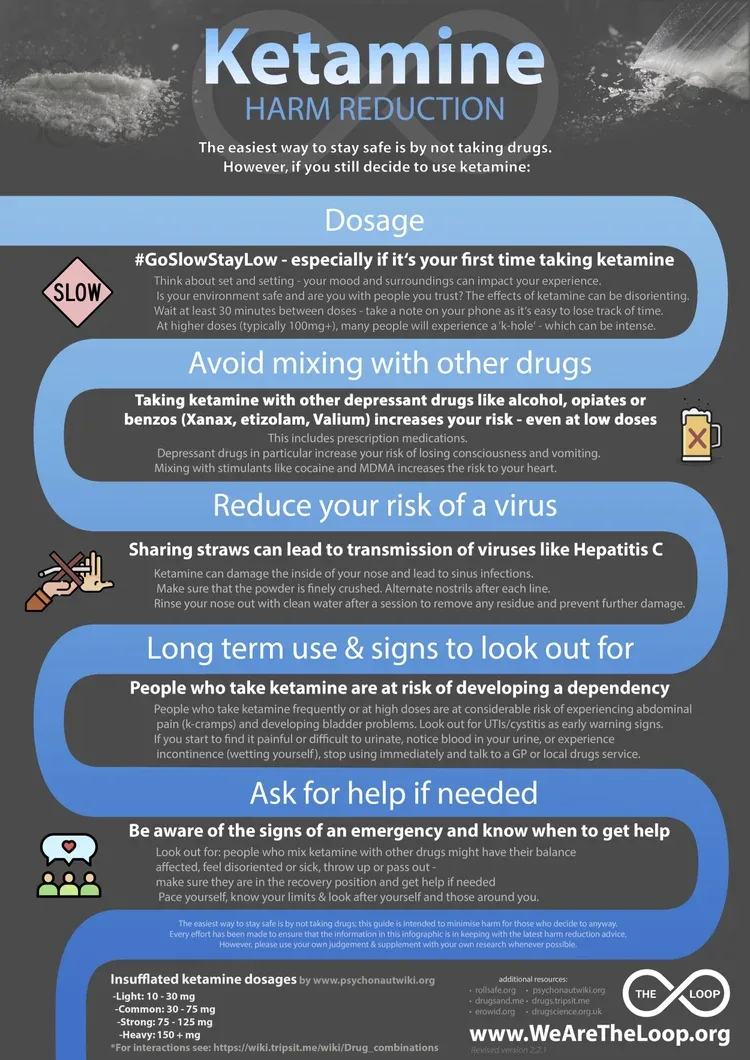

Resourcing for improved harm reduction for people who use ketamine, and ensuring access to such information, including through targeted outreach to key vulnerable populations. This poster produced by the harm reduction and drug checking organisation, The Loop, below is a useful example of pragmatic and accessible harm-reduction information (produced in collaboration with people with lived and living experience of ketamine use and people on the front line of service and harm-reduction provision) that targets young people using (or considering using) ketamine.

Ending the criminalisation of possession of ketamine for personal use, and small scale not-for-profit sharing amongst peers, as part of a wider move towards what civil society has described as the gold standard in decriminalisation policy and practice for all drugs. As explored above, decriminalisation of people who use drugs is a ‘critical enabler’ of any effective public health response to realities of drug use in society. Given the high level institutional support, the fact that the UK already has a no-sanction decriminalisation model legislated in the Psychoactive Substances Act, and is rolling out diversion programmes in police authorities across the country (in practice, very similar to decrim models in countries like Portugal) - the idea that decriminalisation is seen by government as a radical departure is inexplicable. Quite aside from being public health best practice, decriminalisation makes political and economic sense, and already commands significant public support.

In the medium term the government needs to begin an adult discussion around options for legally-regulated availability of ketamine, alongside legally-regulated availability of other drugs with well established markets. While demand for ketamine and other drugs remains, we have a simple but stark choice; either production and availability is responsibly regulated by the relevant Government agencies, or we leave the market to be controlled by organised crime groups and unregulated vendors. There is no third option where these markets magically disappear through increasingly punitive enforcement. Different forms of regulation are needed to address the risks and risk behaviours associated with different drugs - there is no one-size-fits-all model, and we will need to be mindful of how different drugs and related using behaviours intersect with each other in different contexts.

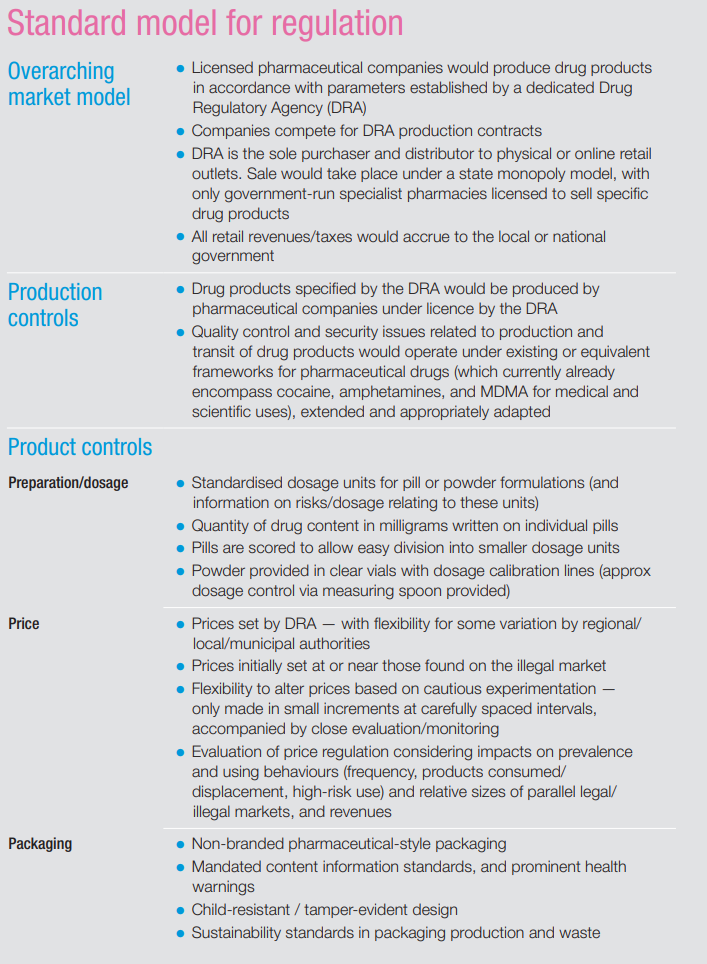

While there has been relatively little attention given to regulation models for ketamine, Transform’s standard regulation model (developed for non-medical stimulant markets - see summary below), that proposes a state monopoly, non-commercial, rationed adult access for personal use (with unbranded pharma-stye products, sold from pharmacy-style outlets by trained vendors, with an emphasis on risk reduction) offers a useful starting point for this important discussion. Transform’s recent guide to psychedelics regulation can also usefully inform this discussion - although its focus is on classic psychedelics that have a different risk profile to ketamine.

-----

An effective response to the growing challenges presented by ketamine use in the UK must follow the evidence of what works - not default to politically-driven performative enforcement measures that have demonstrably failed in the past, and are widely rejected by leading voices in the public health field. Reforms to policy on ketamine must be part of wider discussion about the UK's failing drug laws - including the obvious absurdities of the drug classification system and hopelessly dated and and malfunctioning drug legislation within which it sits.

The Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) is calling for evidence on ketamine use, harms and interventions to inform its recommendations to Government on policy and classification. You can submit evidence here: This call for evidence closes at midday on 19 August 2025