4th November 2021

The Origins of UK Drug Laws

For even more history, explore the Drug Policy Timeline

Drug prohibition in the UK stretches back to the early 20th century. During World War I, restrictions were placed on the possession opium, cannabis and cocaine as part of wartime measures. Although initially temporary, these controls were formalised under the 1920 Dangerous Drugs Act (DDA), which prohibited the possession and unlicensed import or export of opium, heroin and cocaine.

The DDA 1920 was partly a continuation of wartime measures, but also a response to international developments. International Commissions held at Shanghai (1909) and the Hague (between 1911 and 1914) had set out plans for new global controls on opium and other drugs. These were led by America and were, to some degree, an assertion of a rising American power in East Asia (where Britain had previously been responsible for the notorious Opium Wars to prevent China restricting opium imports). However, Britain, Germany other European nations had their own interest in shaping new drug controls to protect their pharmaceutical industries.

The resulting ‘Hague Convention’ marked the first international effort to introduce global restrictions on drug supply, but also set out the principle that drug control policies should be uniform across the world.

Ironically, at the time huge amounts of morphine and cocaine were being smuggled out of the UK to China, India and Japan. However, it was domestic concerns – often driven by wild media reporting – about cocaine use among soldiers, linked to the racist demonisation of Chinese communities through the depiction of opium dens as sites of corruption, that proved decisive. The combination of media scares, racist stereotyping and international pressure provided the crucible out of which early UK drug policy emerged.

However, more considered reflection was not entirely absent from the process. In 1926, a Government committee headed by Lord Rolleston published a report on heroin and morphine addiction. It concluded doctors should be allowed to prescribe heroin to patients where there was a need. This created what would become known as the “British System”: an approach to supervised drug provision that differed significantly from the inflexible prohibition adopted in America under the Harrison Act.

In the following decades, international pressure to establish coordinated global prohibition grew, driven by increasingly dominant America influence. Ultimately, this led to the creation of the 1961 UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, which more formally set out the principles of global prohibition along with a schedule of control based on the perceived risk of different drugs. Critically, all countries that signed up to the 1961 Convention were expected to apply its principles via national legislation.

Changing Cultures

In the 1950s, the use of drugs other than alcohol were increasingly associated with new subcultures. News reporting routinely linked these developments to both emerging youth cultures and Black communities. As in the opium scares of the 1920s, moral panic over drug use provided cover for racism and thinly-veiled attacks on immigration.

In this period, media concerns over drug consumption in the London jazz scene began to drive pressure for greater legal controls. Newspapers began to turn their attention to what was often portrayed as dangerous social mixing between Black and white youth. The 1960s, of course, witnessed a further transformation in both drug consumption and public discourse on drugs. The ‘hippie’ counterculture brought both cannabis and LSD to wider media attention, while use of amphetamines grew – both in mainstream and subcultural contexts.

In 1964, a new Dangerous Drugs Act ratified the 1961 UN Convention and banned the cultivation of cannabis. The UK Government also reconvened a committee (which had first reported in 1961) led by Lord Brain to look at the role of medical prescribing in influencing levels of heroin use. Its findings led to the Dangerous Drugs Act 1967, which retained the British System of prescribing, but required doctors to be licensed by the Home Office. It also set up Drug Dependency Units across England to provide specialist treatment.

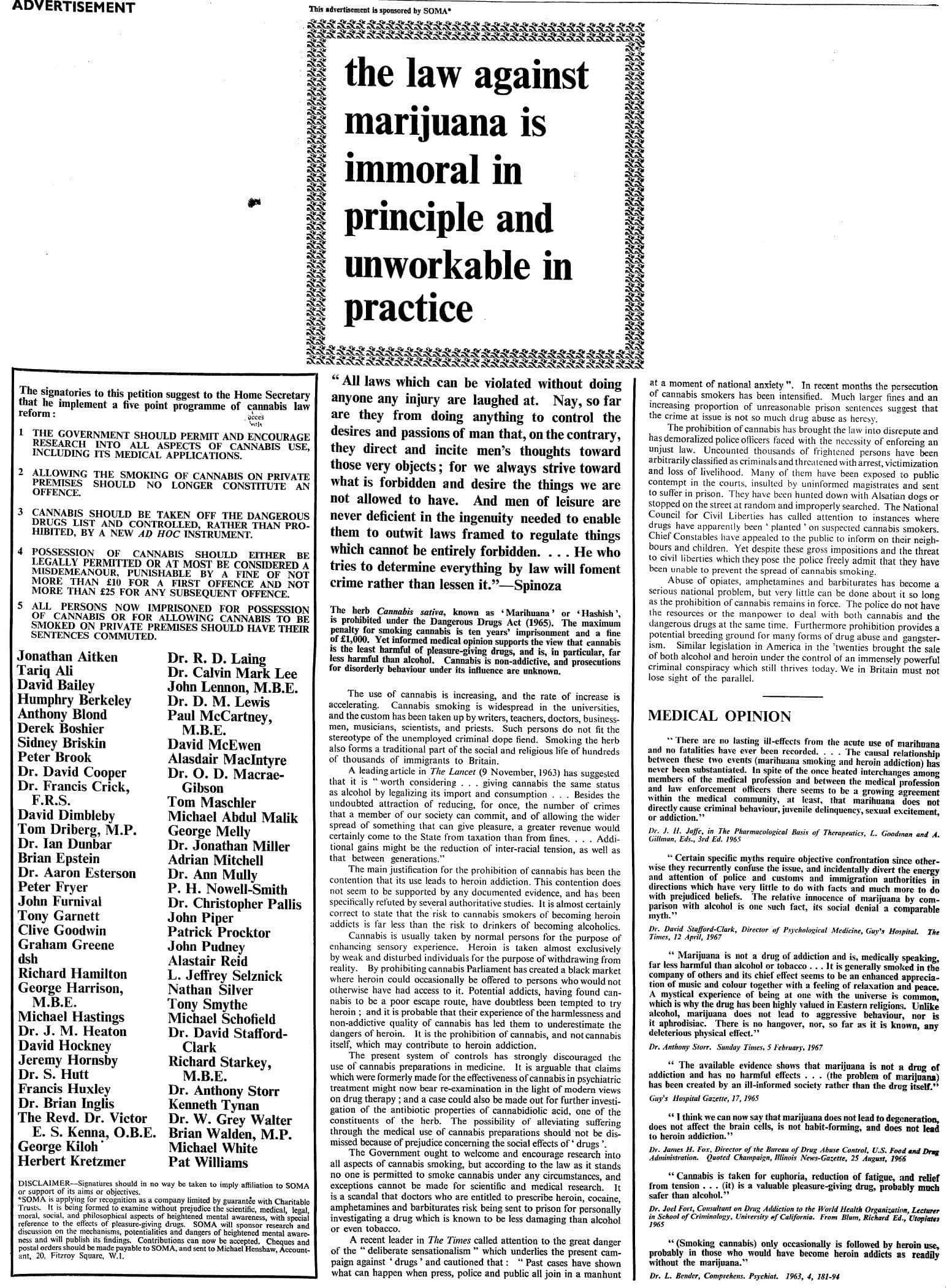

At the same time, the counterculture movement was building pressure for drug laws to be liberalised, including a full page advert taken out in the Times in 1967, which was signed by all members of the Beatles alongside a number of other public figures.

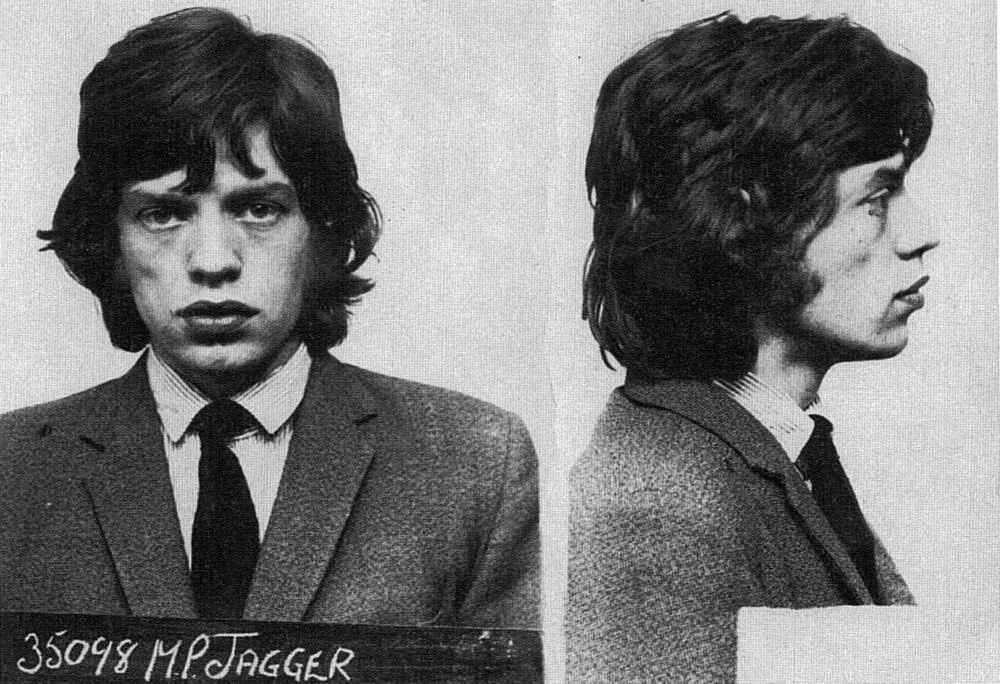

The state response was often heavy-handed. Perhaps most famously, in June 1967 Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were arrested and put on trial for petty drug offences. Keith Richards was sentenced to one year for cannabis offences, while Mick Jagger got three months for amphetamine possession. The decision led to the artist Caroline Coon setting up a new organisation – Release – to support people who fell foul of drug laws. It also led to a now famous Times editorial, which condemned the convictions of Jagger and Richards as excessive and unjustified (their sentences were later quashed).

The Government Responds

In 1967, responding to increasing calls for a rethink, the Government set up a committee chaired by Lady Wootton to review the laws on cannabis and LSD. The report was published in late 1968, and while it didn’t call for legalisation it called for cannabis to be treated differently. The report further amplified political debate around drug policy.

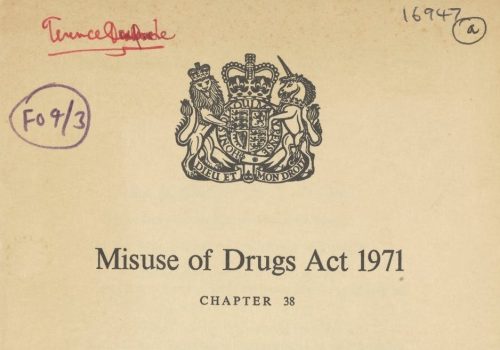

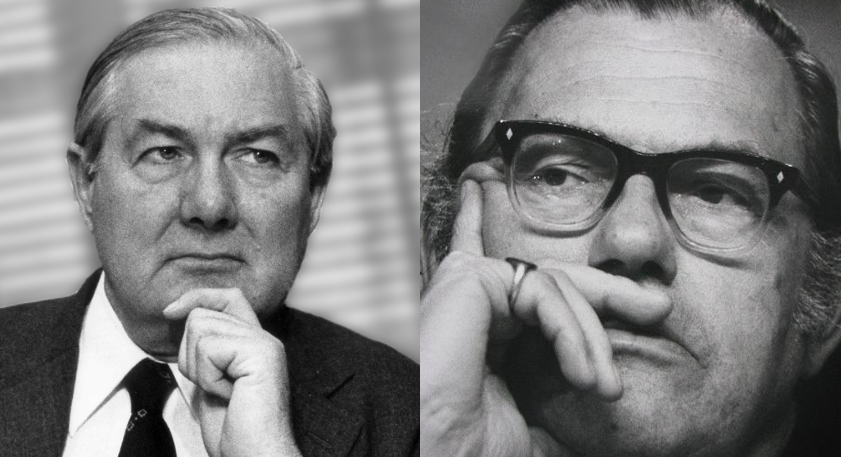

By the late 1960s, there was growing pressure from within the establishment for drug policy to be consolidated. Partly in reaction to the media reporting, and partly because of the recent changes in drug cultures (and their association with political and cultural dissent), consolidation of the law became politically attractive to mainstream political parties. There was also the imperative of building the 1961 UN Convention into UK law. Once again, media-driven anxiety, international pressure and fear of cultural threats to the status quo pushed politicians towards stricter drug policy. In 1970, a new Bill was introduced by the Labour Home Secretary James Callaghan, who had been personally sceptical of Wootton. It was on this basis that the Misuse of Drugs Act (MDA) was developed.

The MDA's path through Parliament was, in the end, somewhat convoluted. Having been introduced by a Labour administration, it was dropped and re-introduced by the Conservative Home Secretary Reginald Maudling following a General Election.

The debates that accompanied its passage show that, in Parliament at least, there was broad support for tightening drug laws – though with some notable exceptions (including an early recognition that drug-led police searches could lead to antagonism and discrimination). The spectre of an excessively ‘permissive’ society, wild claims regarding the risk of drug use to physical and mental health, and a desire to be seen to be ‘doing something’ to protect established social norms all added to the support.

The Bill was approved in May 1971, and received Royal Assent on the 27th of that month. Although it took a further two years to be fully implemented, the law passed in that environment became the foundation for all drug policy in the following fifty years. Despite enormous changes in culture, society and drug availability – and despite a whole raft of expert reports calling for reform – the basic tenets of the MDA remain in place fifty years later.