3rd September 2025

In July 2025, Transform hosted a stakeholder event at Bristol City Hall in partnership with the University of Bristol. The goal was to build on the city’s pioneering harm reduction work and make the case for Bristol to become the first city in England to open a pilot Overdose Prevention Centre (also called supervised drug consumption facilities). This compassionate, evidence-based intervention offers a practical response to the alarming rise in drug-related deaths.

The event brought together a diverse group of stakeholders, including MP Carla Denyer, Green party and Labour party city councillors, healthcare professionals, academics, service providers, and community members, to learn from the evidence, share insights, and establish Bristol as a model city for harm reduction and inclusive recovery.

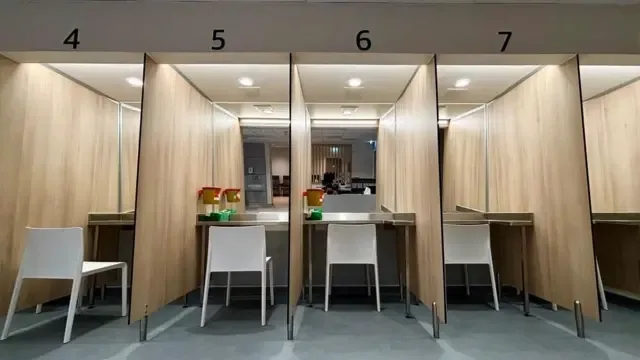

The evening strengthened both the moral and practical case for launching an Overdose Prevention Center OPC in Bristol. This life-saving intervention has already been trialled in over 130 cities worldwide and is now operating in Glasgow. We heard from the man behind Glasgow’s Drug Consumption Facility, the Thistle, who shared insights into what it takes to set up and sustain such a service. The message that emerged was clear: Bristol is ready. What’s missing is explicit permission.

Learning from Glasgow: Dr Saket Priyadarshi on the Thistle drug consumption facility

Dr Saket Priyadarshi, Clinical Lead of the Thistle in Glasgow, shared the story of how Scotland made it possible. Following a change in the Statement of Prosecution Policy by the Lord Advocate (Scotland’s top legal authority) which acknowledged that it would not be in the public’s interest to prosecute an individual attending the facility, the OPC opened in January 2025 without requiring a change to the Misuse of Drugs Act - the UK’s primary drug legislation.

The Thistle is strategically located near existing public injecting sites and was developed through a robust process of community engagement and co-design with people with lived experience. Since launching, the service has:

Welcomed 348 unique service users

Facilitated 4,361 safer consumption visits

Operated 12 hours a day, 365 days a year

Offers drug treatment, blood-borne virus, sexual reproductive health, housing support and GP services.

Unlike many OPC models internationally, the Thistle is considered a gold-standard model because it meets all NHS clinical and governance requirements. Its multidisciplinary team includes nurses, social workers and harm reduction workers employed by the NHS and council.

Dr Priyadarshi described how the facility’s close engagement with service users has not only saved lives but also revealed critical shifts in local drug use patterns. One unexpected finding has been that approximately 70% of clients are injecting cocaine rather than heroin.

Furthermore, earlier this year, a sudden spike in overdoses prompted urgent testing of drug samples which was made possible thanks to trusted relationships with the service users. The cause was identified as nitazine contamination - a powerful synthetic opiate. The Thistle was able to rapidly adapt its harm reduction responses, warned all service users, and helped trigger a national drug alert. This swift and coordinated response illustrates the vital role that OPCs can play in protecting life and public health in an illegal and unregulated drug market.

The facility still operates within the constraints of the Misuse of Drugs Act, including bans on sharing substances even when they have been bought collectively, or providing sterile equipment for smoking or inhalation, which inevitably limit its reach and impact. Nevertheless, the Thistle’s early impact is clear. It is reducing risk, saving lives, and demonstrating what’s possible with the right legal support, clinical leadership, and community trust.

The situation in Bristol

Carly Heath, Bristol’s Night-Time Economy Advisor, opened the event with a call for compassion and pragmatism in nightlife safety:

“Zero tolerance doesn't distinguish between someone who needs help and someone who broke the rules. It tells staff to look away, when they want to lean in,” she said.

Heath advocates for a city-wide culture shift away from prohibition: one that empowers venues, services, and communities to prioritise care, reduce risk, and save lives. Her leadership reflects Bristol’s broader commitment to harm reduction and sets a foundation for integrating OPC’s into the city’s approach to drugs.

Dr Adam Holland, a clinical academic from the University of Bristol reinforced the urgency of addressing the nitazine crisis, which are now being found in drugs sold as heroin and benzodiazepines. Building on earlier contributions, he highlighted the scale of the threat they pose: “Most people don’t intend to take nitazines. They are caught completely unaware and end up overdosing.”

Over 300 deaths in 2024 alone have already been linked to nitazines. Those most at risk are people injecting heroin. The concern is that many people, even if warned about nitazine contamination, often cannot simply stop using. Transitioning to medications such as methadone to manage withdrawal symptoms can take days or even weeks. In the meantime, the risk of overdose remains alarmingly high.

That’s why, Dr Holland argued, OPCs are a sensible, evidence-based response. “OPCs are not a silver bullet - they won’t suddenly stop all drug-related deaths. But they are a practical tool we can add to our toolbox to help protect people and prevent more lives being lost.”

So, why don’t we have them already?

Despite growing support from medical and public health bodies, drug services, and academic experts, successive Parliamentary Committees and the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, the UK Government continues to block their implementation in England. Costs, fear, stigma, and political resistance remain key barriers.

But the lesson from the US fentanyl crisis is clear: the longer we wait, the more people will die. Bristol, and other local areas, have the opportunity to lead where national policy lags. The time to act is now.

Momentum from local and national stakeholders

Steve Rolles, Transform’s Senior Policy analyst, explained that cities like Bristol don’t need to replicate a “gold standard” facility like the Thistle in Glasgow to make progress. The international evidence base shows that OPCs come in a wide variety of models, including lower-cost options such as mobile units or facilities integrated into existing drug services.

“And the other thing I think is really important to point out,” Steve added, “is that the trajectory of change in all of these places has been a bottom-up process. It's been local government, local communities, local activists, local service providers who have driven the change.”

A pilot could go ahead with a multi-agency agreement, involving public health, the police, the council, and service providers. This already happens with needle exchanges and other harm reduction interventions. It doesn’t require a change in law, just political courage and coordinated discretion.

Although Meg Jones from Cranstoun was unable to attend in person, her message was unequivocal:

“Cranston already has a model ready to go - a Memorandum of Understanding would allow us to be up and running as soon as possible, we have our whole organisational backing, including board approval. We would work with partners, and shape the service dependent on local needs.”

MP Carla Denyer, who also attended the event, shared her recent efforts to help make an OPC a reality in Bristol. She explained that she had written directly to the Home Secretary and the Minister for Policing, asking them to follow Scotland’s example by issuing a written statement of non-prosecution - a pragmatic step that would not require any change to the law.

“We’re not asking for new laws, just a letter saying you’re allowed to set up a pilot, like in Scotland. And the government said no.”

The refusal underscores the political obstacles that continue to block life-saving interventions, even when there is growing local consensus, strong clinical evidence, and international precedent. We are delighted that Carla Denyer has chosen to champion this issue. Her intervention reinforces Bristol’s readiness and the call for Westminster to catch up.

What comes next?

Despite the lack of political support from the UK government, the event demonstrated that Bristol has everything it needs to lead the way:

An urgent public health case

Operational readiness from service providers

Cross-party political interest

Community engagement

A track record of innovation (Bristol is the first UK city to host a licensed drug checking service)

Now, it’s about turning that momentum into action. This means:

Developing a multi-agency agreement to support a pilot OPC

Continuing to build community and political support

Pushing for formal police cooperation

Ensuring services are co-designed with people who use drugs

The evening was more than a conversation, it was a collective expression of intent. The energy in the room was hopeful, urgent, and rooted in a deep commitment to care. As Carly Heath put it:

“Harm reduction offers real solutions to drug-related harm. We don’t just want to stop things from going wrong. We want people to feel safe when they ask for help. It’s evidence-led. It’s non-judgemental.”

Bristol has a chance to lead. And the time is now.

Mary Ryder, Transform Drug Policy Foundation