16th November 2018

Misunderstandings and misreporting of actual and proposed changes to Dutch cannabis policy in 2011 have led some opponents of cannabis reform to suggest the country is retreating from its longstanding and pragmatic policy of tolerating the possession, use and sale of cannabis.

This is not the case. In reality, most of the more regressive measures have either not been implemented, have been subsequently abandoned, or have had only marginal impacts. Additionally, there is growing public support for wider, progressive reform, including a system of legal cannabis regulation similar to that adopted in Uruguay, and efforts are underway by numerous municipalities to establish such models of production and supply.

Background

The Dutch approach to cannabis policy has always been fundamentally pragmatic, rather than politically or ideologically driven. When the ‘new’ approach was formally adopted in 1976, it was motivated primarily by a desire to separate the market for cannabis, deemed to be relatively low-risk, from the market for other, more risky illegal drugs. The policy effectively decriminalised the personal possession and use of cannabis for adults, but unlike other decriminalisation approaches that have been implemented elsewhere,1 it additionally tolerated the existence of outlets for low-volume cannabis sales, outlets that eventually became the well-known Dutch ‘coffee shops’. The coffee shops are allowed to operate under strict licensing conditions, which include age-access restrictions, a ban on sales of other drugs (including alcohol), and controls on the shops’ external appearance, signage and marketing. The approach has been broadly successful:

- Just 14% of cannabis users in the Netherlands report that other drugs are available from their usual cannabis source, compared to 52% in Sweden2

- Rates of cannabis use in the Netherlands are equivalent to or lower than those of many nearby countries (which do not have coffee shops),3 and are substantially lower than those of the US4

- Although the use of cannabis in the Netherlands has risen since 1976, this has been in line with wider European trends

- Annually, the coffee shops generate an estimated 400 million euros in tax – money that would otherwise have accrued to criminal profiteers5

Pragmatism also underpins the Dutch policy around more problematic drugs, such as injectable heroin, where they have long followed a harm reduction approach consisting of needle exchanges, substitute opiate prescribing, and some heroin maintenance prescribing. As a result, rates of lifetime heroin use in the Netherlands are a third of those in the US.6

However, the coffee shop system has not been without its problems. In some southern border towns, there have been issues caused by large numbers of visitors from neighbouring countries travelling to the coffee shops.7 More significantly, the quirks of the system’s evolution within an international legal framework that strictly forbids legal production, has led to the paradox that while sales are tolerated and de facto legalised,8 the coffee shops are still supplied via an illegal production system – often involving organised criminal groups.

Opponents of cannabis law reform have tried to paint the Dutch experience in a negative light, but have largely failed as the overwhelmingly positive outcomes speak for themselves. However, when a new conservative government decided to impose a range of new restrictions on the coffee shops in 2011, this was seized upon by critics as evidence that the Dutch ‘cannabis experiment’ was being ended due to its failure. This briefing challenges this narrative by setting out the facts on the key issues.

The ‘wietpas’

One of the most high-profile initiatives for restricting cannabis sales in the Netherlands has been the proposed ‘wietpas’ (or ‘weed pass’) – a system that would effectively make the coffee shops private clubs with a maximum of 2,000 adult members who must be residents of the Netherlands.

Concerns about the proposed move were widespread from the outset, with objections coming from the Netherlands’ largest police union, as well as the mayors of the four largest cities, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, the Hague, and Utrecht, where the majority of the coffee shops are situated. The Amsterdam authorities were particularly vocal; one third of the country’s coffee shops are located in the city, generating valuable economic activity – in particular, income from tourism – with few problems.

Polling in 2012 revealed that 60% of the public thought the wietpas scheme should be stopped, and that 80% believed it would increase the illegal trade.9 In a more recent survey of Dutch judges and prosecutors,10 63.9% said they did not consider the residence requirement to be an effective way of suppressing public disorder around coffee shops. These concerns were well founded: increased street dealing was widely reported in the southern municipalities that adopted such restrictions.

The wietpas was supposed to be rolled out nationwide in 2013, but was essentially abandoned by the new coalition government in October 2012. Nevertheless, municipalities maintain control over local coffee shop policy (hence some do not allow any) and some have maintained a residents-only restriction despite the rejection of the wietpas proposals.11 However, a 2014 survey found that, of those municipalities that permit coffee shops, 85% do not enforce the resident criterion.12

Potency limits on retail cannabis

Another widely reported move was the 2011 announcement that the Dutch government intended to impose a potency limit of 15% THC on the cannabis sold from the coffee shops. Cannabis above this limit would be classed as a ‘hard’ drug and subject to an enforcement response commensurate with its legal status. This proposed move has not yet been implemented and has been opposed by almost every government office that would be involved in enforcing the limit, including the police, and prosecution and forensic services.13 The current government still intends to implement the measure, but its future is increasingly uncertain. Research from the Trimbos Institute has argued convincingly that the potency threshold is arbitrary and that there is no evidence it would reduce health harms.14

Coffee shop closures

The total number of coffee shops in the Netherlands has gradually reduced from around 850 in 1999 to 651 at the end of 2011.15 Some have interpreted this as a trend that will eventually lead to the closure of all the Dutch coffee shops, but in reality it is mostly the result of evolving municipal licensing rules. There is no suggestion that the coffee shop system is being abandoned (see public opinion below) and the number of municipalities in which coffee shops are located has remained the same.

Another development that took place in 2011 was the introduction of a ban on coffee shops within 250 metres walking distance of a high school. Although announced as a child protection measure, it was more of an eye-catching political gesture and was not supported by any meaningful evidence. In practice, however, the licensing powers granted to municipalities mean they can effectively override the ban if they so wish.

Opposition has focused on the fact that in some urban areas – where the majority of the coffee shops are situated – a strict 250-metre rule would require most of them to close. And while the question of how strictly the rule is or will be enforced remains a moot point, it means that in Amsterdam at least 28 are currently due for phased closure between 2014 and 2016.

Public opinion

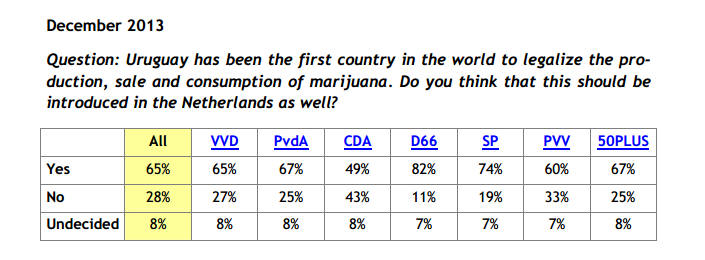

Public support for the coffee shops has increased throughout their existence. The most recent polling, carried out in December 2013, shows a significant majority of the Dutch population would like to go further, with 65% supporting the kind of legal cannabis regulation implemented in Uruguay.16

New efforts to address the ‘backdoor problem’

Perhaps the most justifiable concern with the coffee shop system is the ‘backdoor problem’, whereby sales of cannabis are tolerated (the drug can leave the coffee shops via the front door), but production and cultivation (i.e. the supply chain that leads up to the back door of the coffee shops) remain prohibited. This has led to concerns about the links between the coffee shops and organised crime.

However, if there is any truth in the claims about such links, it is almost entirely because of the legal paradox in which supplying cannabis to the coffee shops is a criminal act, while selling cannabis via the shops is (effectively) not.

Furthermore, claims that 80% of the cannabis cultivated in the Netherlands is destined for export and controlled by criminal organisations have been exposed as unevidenced propaganda.17 Efforts to resolve this issue through some form of regulated production and supply to the coffee shops have been ongoing for many years, but have recently been given fresh impetus by developments in other countries, such as the growth of Spain’s cannabis social clubs18 and the legalisation of cannabis in Uruguay and two US states.

41 municipalities have endorsed a manifesto calling for the production of cannabis to be regulated, and 25 of the 38 biggest municipalities have applied to the Minister of Justice for permission to experiment with various forms of authorised cannabis production and wholesale supply.19 These include the licensing of private growers and municipally run cannabis farms. So far, no such applications have been approved, however the mayor of one municipality in the South, Heerlen, has publicly expressed his willingness to proceed without formal permission.

In addition, the majority of supporters of both the political parties that currently make up the Netherlands’ coalition government are in favour of legally regulating the supply of cannabis,20 and the second biggest party, Democrats 66, which is currently in opposition, is preparing a bill that would realise this goal.21 Consequently, all signs point to there being broad popular and political support for continuing the country’s historically progressive stance on cannabis.

Further reading

- Rolles, S. and Murkin, G. (2013) How to Regulate Cannabis: A Practical Guide, Transform Drug Policy Foundation.

- Grund, J-P. and Breeksema, J. (2013) Coffee Shops and Compromise: Separated Illicit Drug Markets in the Netherlands, Global Drug Policy Program, Open Society Foundations.www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/Coffee%20Shops%20and%...

- The Transnational Institute, Drugs and Democracy. http://www.tni.org/work-area/drugs-and-democracy

- DrugWarFacts.org, ‘The Netherlands Drug Control Data and Policies’. www.drugwarfacts.org/cms/?q=node/1212#sthash.P8h7c9ur.dpbs

References

- Rosmarin, A. and Eastwood, N. (2013) A Quiet Revolution: Drug Decriminalisation Policies in Practice Across the Globe, Release. http://www.release.org.uk/sites/release.org.uk/files/pdf/publications/Re...

- European Monitoring Centre on Drugs and Drug Addiction (2013) Further insights into aspects of the EU illicit drugs market: summaries and key findings, p. 18. http://ec.europa.eu/justice/anti-drugs/files/eu_market_summary_en.pdf

- European Monitoring Centre on Drugs and Drug Addiction (2012) ‘Cannabis: last year prevalence among all adults (15-64 years old)’. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/countries/prevalence-maps

- MacCoun, R. J. (2011) ‘What can we learn from the Dutch cannabis coffeeshop system?’, Addiction, vol. 106, no. 11, pp. 1899-1910.

- Grund, J-P. and Breeksema, J. (2013) Coffee Shops and Compromise: Separated Illicit Drug Markets in the Netherlands, Global Drug Policy Program, Open Society Foundations, p.52.www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/Coffee%20Shops%20and%...

- DrugWarFacts.org, ‘The Netherlands Drug Control Data and Policies’. www.drugwarfacts.org/cms/?q=node/1212#sthash.P8h7c9ur.dpbs

- For more discussion, see chapter on cannabis tourism, page 197, in Rolles, S. and Murkin, G. (2013) How to Regulate Cannabis: A Practical Guide, Transform Drug Policy Foundation.

- For more on the distinction between de facto and de jure legalisation, see Rolles, S. and Murkin, G., op. cit., pp. 30-31.

- Peil.nl (2013) ‘Cannabis opinion polls in the Netherlands’ (translated by the Transnational Institute).www.druglawreform.info/images/stories/documents/Cannabis_opinion_poll_in...

- Lensink, H. and Husken, M. ‘De rechter is het zat’, Vrij Nederland, 10/12/13. www.vn.nl/Archief/Justitie/Artikel-Justitie/De-rechter-is-het-zat.htm

- For more detail on the wietpas see: Blickman, T., ‘Cannabis pass abolished? Not really’, Transnational Institute blog, 30/10/13. www.druglawreform.info/en/weblog/item/4005-cannabis-pass-abolished-not-r...

- Maalsté, N. et al. (2014) Verplicht nummer Onderzoek naar de lokale handhaving van het coffeeshopbeleid, Access interdit. http://accesinterdit.nl/images/2014-02/verplicht-nummer-def_1.pdf

- The possibilities for regulating potency in legal cannabis products, and the issue of potency-related harm, are discussed in Rolles, S. and Murkin, G., op. cit., pp. 107-116.

- Trimbos Institute (2013) THC-concentraties in wiet, nederwiet en hasj in Nederlandse coffeeshops.www.trimbos.nl/webwinkel/productoverzicht-webwinkel/alcohol-en-drugs/af/...

- Bieleman, B., Nijkamp, R. and Bak, T. (2012) Coffeeshops in Nederland 2011. Groningen: Intraval. http://www.intraval.nl/pdf/b108_MCN11.pdf

- Peil.nl, op. cit.

- Blickman, T. and Jelsma, M., ‘The Netherlands is ready to regulate cannabis’, Transnational Institute blog, 19/12/13.http://druglawreform.info/weblog/item/5219-the-netherlands-is-ready-to-r...

- Rolles, S. and Murkin, G., op. cit., pp. 62-65.

- de Graaf, P. ‘Burgemeesters werken aan manifest voor legalisering wietteelt’, Volkskrant.nl.http://www.volkskrant.nl/vk/nl/2686/Binnenland/article/detail/3565577/20...

- Blickman, T., ‘Majority of the Dutch favour cannabis legalisation’, Transnational Institute blog, 04/10/13.www.druglawreform.info/en/weblog/item/4960-majority-of-the-dutch-favour-...

- DutchNews.nl, ‘D66 Liberals to draft regulated marijuana production proposal’, 20/11/13.http://www.dutchnews.nl/news/archives/2013/11/d66_liberals_to_draft_regu...