16th November 2018

The core argument made by opponents of legal regulation is that any regulated market for cannabis would inevitably fuel a significant rise in use and associated harms – particularly among young people. So inevitably, as the first jurisdiction in the world to implement a legally regulated market for non-medical cannabis use, Colorado is under intense scrutiny, with advocates keen to demonstrate its successes, and prohibitionists keen to highlight its failings.

Given that Colorado’s cannabis market only began trading in January 2014, it is not yet possible to draw firm conclusions about longer-term impacts. But a review of early evidence on key indicators suggests that, aside from some relatively minor teething problems, the state’s regulatory framework has defied the critics, and its impacts have been largely positive.

There has been no obvious spike in young people’s cannabis use, road fatalities, or crime, and there have been a number of positives, including a dramatic drop in the number of people being criminalised for cannabis offences; a substantial contraction in the illicit trade, as the majority of supply is now regulated by the government; and a significant increase in tax revenue, which is now being spent on social programmes. Consistent public support for legalisation also suggests Coloradans perceive the reforms to have been a success. Where challenges have emerged, for example around cannabis edibles, the flexibility of the regulations has allowed for modification to address them.

Background

In 2012, Colorado and Washington State became the first jurisdictions in the world to legalise cannabis markets for non-medical use. The reforms were passed through ballot initiatives, with voters in both states choosing legalisation by a solid margin. Colorado’s Amendment 64 was approved in November 2012, with the state’s first retail stores opening on January 1, 2014, following the development of a comprehensive regulatory infrastructure devised by an expert task force.1

Cannabis use

Unfortunately, it is too early to say what the immediate impact of a commercial cannabis market has been on consumption, as the latest data on use only goes up to 2013, and the first retail cannabis stores only opened in 2014. However, Amendment 64 became law on 10 December 2012, enabling adults aged 21 or older to possess cannabis, grow up to six cannabis plants themselves, and give up to one ounce to other adult users. So while not particularly revealing at this stage, the available data provides a limited indication of the effect that a year of such legal activity has had on cannabis consumption.

- According to the biennial Healthy Kids Colorado Survey (HKCS), ‘The trend for current and lifetime marijuana use [for high school students in Colorado] has remained stable since 2005.’2 Marginal falls were observed, but deemed not statistically significant

- The HKCS found that, in 2013, 20% of high school students admitted using cannabis in the preceding month, and 37% said they had at some point in their lives.3 Both of these figures are lower than the national averages (23.4% and 40.7% respectively), which are recorded by the National Youth Risk Behaviour Survey4

- Looking at a different youth demographic, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that, although cannabis use among adolescents (aged 12-17) and young adults (aged 18-25) both rose in Colorado between 2012 and 2013, these increases were not statistically significant

- While arguably a lesser public health concern, there have, however, been statistically significant increases in cannabis use among adults in Colorado in recent years, but these are in line with broader national patterns, including states that have not legalised cannabis.5 Between 2011 and 2013, past-month cannabis use among those aged 26 and above rose from 7.6% to 10.1%, while use among those aged 18 and over rose from 10.4% to 12.6%6

- A year after the retail cannabis stores opened, a Denver Post survey asked: ‘Since marijuana became legal, has your use changed?’ 13% said it had decreased, 17% increased and 70% stayed the same7

In summary, to date, the dramatic increases in cannabis use predicted by some have not materialised, with any rises broadly in line with changes seen elsewhere in the US. While recorded adult use has risen (and was rising even before the legalisation vote in 2012), this increase may, in part, reflect a greater willingness to admit to cannabis use now that it is legal, rather than an actual change in the number of users. The novelty and huge publicity around the newly legal drug market may also have contributed to the rise in use, as curious older users in particular exercise their new freedoms. It is too early to say what will happen as this novelty wears off.

Health harms

Assessing the health impacts of cannabis use is challenging, and isolating any impacts of a policy change related to cannabis use even more so. However, the following trends have been observed:

- The number of treatment admissions with cannabis as the primary substance of abuse has risen from around 5,500 in 2005, to around 6,900 in 2009, before falling to around 5,500 again in 20138

- Since 2000, ‘cannabis-related’ A&E admissions have risen consistently. More recently, admissions rose from 8,198 in 2011, to 12,888 in 2013.9 A caveat is that ‘cannabis-related’ means the drug was ‘mentioned’, rather than identified as the cause of the admission (again, the legal change may have made people more forthcoming about their use). There have also been changes in how, and how consistently, emergency room data is reported, which is likely to have contributed to the increase

- Accidental ingestions of cannabis by children have risen, although in real terms, the numbers remain low – for under-9s, the number rose from 19 in 2011, to 45 in 2014,10 all of whom made full recoveries (for perspective, the equivalent 2014 numbers for under-5 pediatric exposures to painkillers were 2,178, and 1,422 for cleaning products11). The reduced stigma associated with attending A&E post-legalisation may also go some way to explaining this trend

Crime

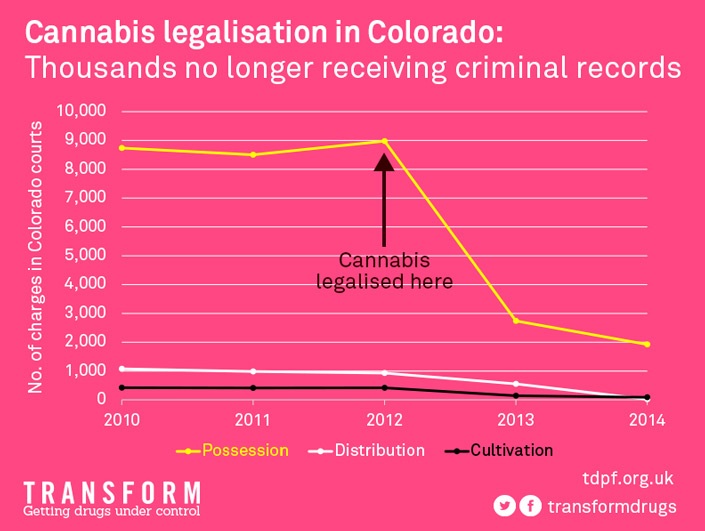

Unsurprisingly, arrests for cannabis possession have dropped dramatically – by nearly 80% – since 2012, an obvious direct and positive outcome of the change in the law.12 And while it is disappointing that black people are still disproportionately arrested for cannabis-related offences, there has nonetheless been a significant drop in criminalisation across the board.

There has, however, been a contrasting rise in citations for public consumption of cannabis. In the first nine months of 2014, police wrote 668 tickets, up from 117 for the same period the year before.13 Despite the size of this increase, these are still small numbers, and their significance should not be overstated given that public cannabis consumption is classed as a minor administrative offence. This trend is likely explained by an absence of legal consumption venues (outside of private homes), a poor initial understanding of the new law (particularly among out-of-state visitors, who do not have any designated consumption spaces), and changes in policing priorities now that resources are no longer needed for other cannabis offences.

Other crime data – on, for example, theft, sexual assault, and violent crime – has been seized on by both advocates and critics to support their positions. Figures for some crimes have gone up, and some have gone down, with considerable variation between demographics and regions. With the link between most of these variables and cannabis legalisation generally unclear, it is probably unhelpful to infer much from them in the absence of more focused, longer-term comparative studies.

Estimates from the Colorado Department of Revenue suggest that 41% of the total demand for cannabis is not being met by licensed recreational vendors.14 Instead, it is being met by (as they describe them) ‘grey-market’ medical suppliers or ‘black-market’ illicit production. This means that 59% of the recreational market has now been legalised, regulated, and taxed, which, even if total demand has increased marginally, still represents a significant contraction in the untaxed criminal market.

Tax revenue

Some critics have noted that tax revenues from the first year of legal cannabis sales did not match initial predictions (which curiously implies they are critical of not enough legal cannabis being sold and used).15

There are three types of state taxes on recreational cannabis: the standard 2.9% sales tax, a 10% ‘special marijuana sales tax’, and a 15% excise tax on wholesale cannabis transactions (to put this in perspective, cigarettes are taxed in Colorado at 3.74%). For August 2015, Colorado collected a total of $11.2 million in recreational taxes and fees, and $2 million in medical taxes and fees, bringing the cumulative revenue total to almost $86.7 million for the first eight months of 2015. The state is on course to collect over $125 million by the end of the year.

The terms under which retail cannabis sales were legalised require the first $40 million of the excise tax revenue to be spent on Colorado school construction projects. The first eight months of 2015 brought in $22.9 million in excise tax towards this total, with a record $3.3 million in August alone. This compares with $13.3 million for all of 2014.16 17

Sales of medical cannabis have been more resilient than expected, possibly because taxation, and hence prices, remain substantially lower than for non-medical supplies. Taken together, the legal medical cannabis industry and legal recreational cannabis industry in Colorado generated $700 million in sales in 2014 ($386 million and $313 million respectively).18

Driving under the influence of cannabis

Data for fatalities involving drivers testing positive for cannabis is available from the Colorado Department of Transport, which recorded 40 in 2003, and most recently, 36 in 2013 (ranging from 20 in 2004, to 56 in 2011).19 No obvious trend is apparent from these figures, and there are ongoing challenges in determining the extent of the link between blood-THC levels and impairment.20

A rise or fall in the number of positive roadside tests is an even less useful indicator, as it can indicate changes in policing activity (the number of tests carried out, or types of drivers targeted), rather than actual changes in drivers’ behaviour, whether as a result of legalisation or not.

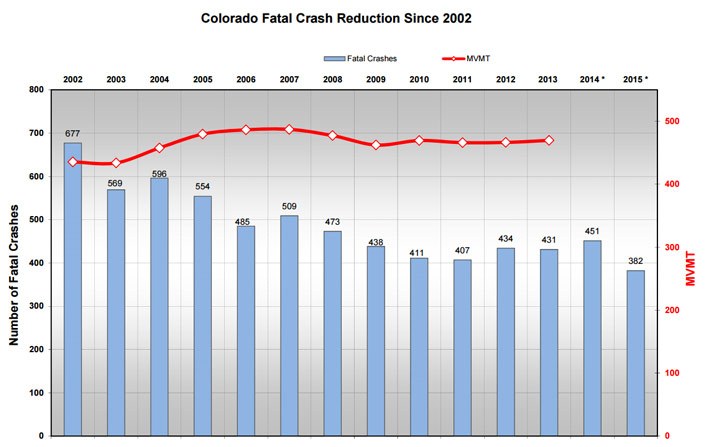

Nevertheless, there has, reassuringly, been no jump in total road fatalities, which remain at near-historic lows.21 This trend is likely to be driven primarily by the ongoing decline in people driving under the influence (DUI) of alcohol, which in itself indicates how DUI incidents do not inevitably rise because a drug is legal. Instead, cultural norms and public education are the key factors.

Public opinion

An opinion poll undertaken by the Denver Post found that levels of support for legalisation in Colorado were virtually unchanged from the 2012 vote a year after the first retail cannabis stores had opened.22 Subsequent polls have shown similar levels of support. A poll conducted in February 2015 found that 58% of Colorado voters supported keeping cannabis legal, while 38% were against it.23

Regulatory flexibility

It is clear from an initial early assessment that Colorado’s reforms are, according to most metrics, far from the disaster predicted by opponents of legalisation. Of course, given the novelty of the market, caution is needed in drawing wider conclusions about the success of cannabis regulation from the Colorado data. The state’s regulatory framework is still essentially in its roll-out phase and social norms around retail sales, and novel products like edibles and concentrates are yet to be firmly established (even if the pre-existing commercial medical cannabis market has helped mitigate any cultural shocks). Colorado also remains (for now) an ‘island’ of legalisation, surrounded by prohibitionist states. This may be distorting a number of outcomes relating to cross-border trade with neighbouring states (two have already launched legal challenges24).

Inevitably, there have been some mistakes made and some challenges have been inadequately anticipated – in particular the need for more stringent regulation of edibles. But even here, the ability of the regulatory system to respond positively to emerging evidence of problems has been reassuring. Now, only single servings containing up to 10mg of THC can be sold, all packaging of edibles must be child-proof, and all edibles must be clearly marked as containing cannabis.25

Over-commercialisation?

Colorado’s cannabis market has also been subject to some criticism from within the pro-legalisation movement for being too commercialised. Whether this is the case remains to be seen, and the data now emerging will provide an instructive contrast to that coming from other US states, and other types of cannabis markets, such as those in Uruguay,26 Spain,27the Netherlands28 and elsewhere. What is clear is that even if the Colorado model does turn out to be sub-optimal in some respects, it is a dramatic improvement on the prohibition it has replaced, and is providing invaluable evidence to guide other jurisdictions as they legally regulate cannabis. As a result, its very existence is already undermining decades of cannabis prohibition, not just in the US, but worldwide too.

References

- State of Colorado (2013) ‘Task Force Report on the Implementation of Amendment 64: Regulation of Marijuana in Colorado’.

- Healthy Kids Colorado Survey (2013) ‘Marijuana Overview of 2013 Data’.

- Ibid.

- National Youth Risk Behavior Survey (2013) ‘Trends in the Prevalence of Marijuana, Cocaine, and Other Illegal Drug Use. National YRBS: 1991-2013’.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014) ‘Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables’, Table 1.24B.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014) ‘National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Comparison of 2011-2012 and 2012-2013 Model-Based Prevalence Estimates (50 States and the District of Columbia)’, Table 3.

- Simpson, K. (2014) ‘Poll: One year of legalized pot hasn’t changed Coloradans’ minds’, The Denver Post, 28.12.14.

- Mendelson, B. (2014) ‘Patterns and Trends in Drug Abuse in Denver and Colorado: 2013’, National Institute on Drug Abuse.

- Rocky Mountain High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (2014) ‘The Legalization of Marijuana in Colorado: The Impact’.

- Barker, E. A. et al. (2015) ‘Marijuana Exposures Reported to the Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center’.

- Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center (2014) ‘Colorado 2014 Annual Report’.

- Drug Policy Alliance (2015) ‘Marijuana Arrests in Colorado After the Passage of Amendment 64’.

- Cotton, A. (2014) ‘Ignorance is bliss? Citations for public use of pot is increasing', The Denver Post, 28.12.14.

- Colorado Department of Revenue (2014) ‘Market size and demand for marijuana in Colorado’.

- Ingold, J. (2014) ‘Colorado lawmaker seeks marijuana tax review amid disappointing sales’, Denver Post, 12.08.14.

- Colorado Department of Revenue (2015) ‘Marijuana Taxes, Licenses, and Fees Transfers and Distribution. August 2015 Sales Reported in September 2015’.

- Hernandez, E. (2015) ‘Colorado monthly marijuana sales eclipse $100 million mark’, The Denver Post, 09.10.15.

- Ingraham, C. (2015) ‘Colorado’s legal weed market: $700 million in sales last year, $1 billion by 2016’, Washington Post wonkblog, 12.05.15.

- Colorado Department of Transportation (2014) ‘Drugged Driving Statistics’. Rolles, S. and Murkin, G. (2013)

‘How to Regulate Cannabis: A Practical Guide’, Transform Drug Policy Foundation.

Department of Transportation (2015) ‘Colorado Historical Fatal Crash Trends’.

Simpson, K., op. cit.

Lerner, A. (2015) ‘Poll: Colorado residents still back legal pot’, Politico, 24.02.15.

Duggan, J. (2014) ‘Jon Bruning files lawsuit over Colorado’s legalization of marijuana’, omaha.com, 18.12.14.

Colorado General Assembly (2014) ‘House Bill 14-1366: Concerning reasonable restrictions on the sale of edible marijuana products’.

Murkin, G. (2014) ‘Uruguay announces final regulations for new, legally regulated cannabis trade’, Transform Drug Policy Foundation, 07.05.14.

Murkin, G. (2015) ‘Cannabis social clubs in Spain: legalisation without commercialisation’, Transform Drug Policy Foundation, 06.01.15.

Rolles, S. (2014) ‘Cannabis policy in the Netherlands: moving forwards not backwards’, Transform Drug Policy Foundation, 12.03.14.