23rd March 2025

Last week saw the 68th UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) held in Vienna - the annual gathering of UN member states to supervise the global drug control system. Three key takeaways for Transform are discussed below: The passing of a historic Colombian resolution on review of the global drugs control system; the rising profile of the coca/cocaine regulation debate, and the challenges of a belligerent new US administration seemingly determined to disrupt global governance under the UN system

The CND is the central policy-making body of the United Nations drug control architecture - its various mechanisms and functions usefully explained in this primer video from IDPC. (or the official CND website is here). Transform has been participating in the CND for almost 20 years - in 2007 becoming the first NGO with a drug reform platform specifically focusing on regulation to be awarded UN ECOSOC special consultative status.

The CND has a number of components. Alongside other formal proceedings, including the ritual scheduling (prohibiting) of various emerging drugs within the drug treaty framework, a series of thematic resolutions, nominally offering guidance on different aspects of addressing the ‘world drug problem’, are proposed and negotiated - and form the substantive policy output of the event.

Alongside the formal proceedings, the CND hosts a crowded calendar of over 175 side events hosted by member states, UN agencies and NGOs. For civil society, the CND is a unique opportunity for advocacy, networking and knowledge exchange - with an extraordinarily diverse audience - ranging from progressive reform advocates to dogmatic defenders of the drug war, including for example member states with legal cannabis, and others still executing people for cannabis offences. It is a rare moment when such a wide spectrum of views move outside their bubbles and interact in the same space.

A major breakthrough for scrutiny of the International drugs control system

From a reform perspective the most consequential resolution was tabled by Colombia (with other resolutions mostly retreading old ground on topics like prevention and alternative development). The Colombian resolution calls for an independent expert group to be appointed, under the auspices of the UN Secretary General, to scrutinise the global drug control system and make recommendations for its more effective implementation. The panel will be composed of 19 members: ten selected by the CND and its regional groups, five appointed by the UN Secretary-General, three by the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), and one by the World Health Organization (WHO). Progress on this process will be presented at the 69th and 70th sessions of the CND, in 2026 and 2027.

Superficially this may appear to be just a call for another meeting. But its significance lies in the fact that the call for scrutiny of the drug control system is coming from within the system itself rather than from civil society or other critics on the outside. A call for such an independent expert group to be convened within the UN system has actually been a long standing strategic goal for many in the reform movement that dates back to before the 2016 UN General Assembly Special Session on Drugs. It represents a critical acknowledgement - made explicitly in the preambular paragraphs - that the system is not achieving its objectives and that the ‘world drug problem’ is evolving in unforeseen ways presenting new challenges that urgently need to be addressed.

These new challenges are only obliquely alluded to in the resolution text, rather than being identified specifically, but inevitably include the growing tensions between the limits of the treaties and emerging state practice around drug regulation, as well as issues of ‘system coherence’. This concept speaks to how the implementation of the drug control system is increasingly at odds with wider UN system goals and mechanisms, including, but not limited to, human rights instruments and the sustainable development goals. The call from the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights last year for an end to the 'war on drugs', and the regulation of all drugs - only highlights the extent of these growing tensions, not only between member states, but with the UN system itself.

The fact that the resolution was tabled by Colombia is also important. Colombia is on the front line of the war on drugs; for them it is not a rhetorical term, but a lived reality. It is a war that has not only failed in its core objectives to reduce production and use of cocaine, but one that has undermined governance, fuelled corruption, accelerated environmental damage, violence and insecurity, and left a trail of death and destruction in its wake for more than 50 years. Speaking to the CND plenary session after the resolution was passed by Vote, Colombian Ambassador to the UN in Vienna, Laura Gil, noted:

“Colombia supplies less than 5% of the illegal drug market, yet we are not proud of this situation. But why does every Colombian feel that the global drug problem rests on their shoulders? This panel is an invitation, within the framework of the conventions, to rethink ourselves, to highlight the significance of the principle of common and shared responsibility. My country has sacrificed more lives than any other in the war on drugs imposed on us. We have postponed our development, dedicating our best men and women and a good part of our national budget to fighting illicit trafficking. We want new, more effective ways to implement the global regime. This does not have to be a confrontation among us, the members of the CND, but rather a manifestation of our commitment to combating transnational crime . ”

The next steps for implementing the resolution are a little murky. To build a consensus its wording was watered down somewhat in negotiations, leaving considerable scope for it to be shaped in different - likely conflicting - directions. Ensuring the panel members are genuinely independent experts will be critical, and how the terms of reference are fine tuned from the guidelines established in the somewhat ambiguous wording of the resolution will be a parallel challenge. Another major hurdle will be ensuring the review is funded - member states will need to step up - these panels tend to be expensive (probably over $1million for the 2 year process), and care will be needed by the General Secretary to ensure funding does not compromise independence.

These questions will play out in the coming months. But what we have now is an opportunity, perhaps for the first since the 2016 UNGASS, for some meaningful high level scrutiny of the failed and malfunctioning drug control system system. It is an opportunity to map a path to a long overdue system modernisation that works in the interests of all UN member states, and one that Transform and colleagues throughout the global reform movement will be working hard to realise.

For more analysis see this blog from Dejusticia in Colombia, and this blog from IDPC

A rising profile for coca/cocaine regulation in CND debates

Transform’s official side-event this year focused on the coca/cocaine issue - particularly the emerging debates around models of cocaine regulation. It is a complex issue - but one we have been keen to open up in high level forums. Where cannabis regulation has proved politically contentious and technically challenging, cocaine regulation is significantly more so. A key part of the challenge is the reality of one drug - the cocaine alkaloid - existing in different preparations; coca leaf, cocaine powder, and crack cocaine, associated with very different levels of risk, consumption behaviours, markets, and policy challenges.

The coca leaf issue loomed large this year for a number of reasons. The WHO is conducting a ‘critical review’ of the leaf at the request of the Bolivian and Colombian Governments, to assess whether it should be recommended for rescheduling under the drug treaty system (where it currently exists in the most restrictive schedule one, alongside heroin and cocaine). The possibility also exists for coca leaf to be descheduled, i.e. removed from the treaties altogether to allow its traditional and ceremonial use, and potentially development of new markets as a mild stimulant (somewhat comparable to coffee), in speciality teas for example. The Bolivian Vice president attended the CND specifically to speak to the coca issue. There is precedent within the treaty system for the plant form of drugs to exist outside of international controls whilst the extracted drug is specifically prohibited (for example magic mushrooms / psilocybin). For a detailed overview of the coca review - see TNI’s Coca resources, in particular the Coca chronicles parts 1, 2, and 4.

Cocaine regulation was the specific focus of Transform’s side event - which included presentations from experts on the front line of the global cocaine regulation debate in Switzerland, Colombia, and the Netherlands (we will share the video on our youtube channel shortly). The reality of multiple jurisdictions now exploring the possibilities of cocaine regulation - as a pragmatic response to the catastrophic generational failure of the drug’s prohibition - has helped at least normalise the debate on the subject in the UN arena. What was considered taboo when Transform held its first side event on the subject in 2020 is now a major topic of discussion - with multiple side events this year directly engaging with coca and cocaine regulation, and significant new institutional endorsements for regulation (of drugs beyond just cannabis) from The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, and Amnesty International, the world biggest Human Rights NGO.

Another critical but long overlooked dimension of the cocaine regulation debate concerns the impacts of the illegal trade on the environment - particularly deforestation and biodiversity loss in the Amazon. Transform is a member of the International Coalition on Drug Policy Reform and Environmental Justice, highlighting how the war on drugs is fuelling environmental harms and undermining governance, climate mitigation and indigenous rights in the world's most important yet vulnerable ecosystems. A growing presence for the coalition was critical at this CND, as the COP 30 on climate change in Brazil approaches. The coalition was able to bring indigenous community representatives from The Amazon region to speak directly to the lived experience of the intersecting war on drugs and environmental destruction, at a series of side events, and meetings with UN agencies, member state delegations and other NGOs.

Established international relations upended by a belligerent new US administration

The wild card at this year’s CND was the new US administration. How would they engage? The Historical context is the US acting as powerful and resolute defenders of the prohibitionist status quo. Indeed the US have done as much as any member state to establish and champion the UN drug control system in its current form. Their role as the chief defenders of the old-school drug war model had, however, begun to shift - most notably last year’s historic overdose response resolution - and its inclusion of harm reduction language for the first time at the CND. But if these had been signs of emerging public health pragmatism in the context of an unprecedented overdose crisis, it was nowhere to be seen this year.

Instead the US morphed into a belligerent and obstructivist role that we are more familiar with seeing from Russia and China. At several points they behaved like power-drunk MAGA frat-boy vandals; seemingly determined to disrupt, but with little apparent strategy. This manifested in early negotiation statements that they would not accept any reference to the Sustainable Development Goals (a core system wide project of the UN that the US had been central in negotiating - but now apparently a socialist conspiracy to undermine US sovereignty); the WHO (that has a treaty mandated role within the drug control system, but that the new US administration has defunded); and Gender (repeatedly making incendiary comments opposing what they described as ‘gender ideology’). They even refused to affirm, but only note UN commitments to human rights (the drafting of the UN charter on Human Rights was famously led by Eleanor Roosevelt).

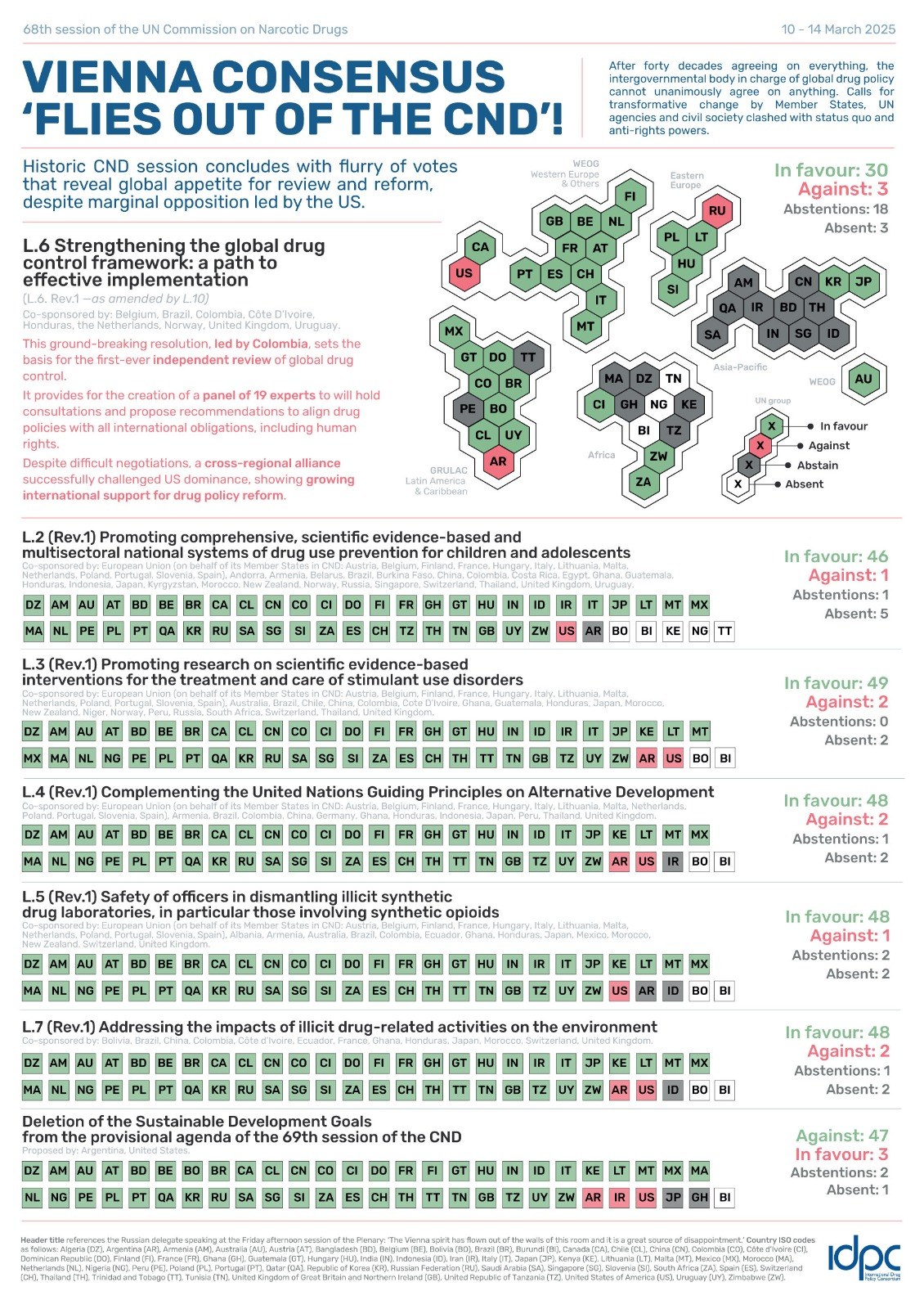

For these obnoxious positions - They were unsurprisingly marginalised. In the votes they demanded on every resolution (again, completely unprecedented), they were only supported by a small number of abstentions and supportive votes from Argentina (apparently the administration's new client state), and on the Colombia resolution - from Russia. The sight of the US voting with only Russia (and Argentina) - was a shocking turn around after recent years of hostility between the two global powers, particularly over the Ukraine issue. China and Russia, so long the disruptive conservative forces in CND deliberations were uncommonly quiet - apparently sitting back with popcorn and letting the US do their dirty work. The US had also arrived at the CND having announced its plans to defund the UN Office on Drugs and Crime - cutting as much as 40% of its budget in one fell swoop - and leading to the many of the Vienna staff being informed of likely redundancies in the days before the biggest event in the institutional calendar

In some respects it was quite conflicting for many reform advocates. The ‘Vienna consensus’, whereby ‘nothing is agreed until everything is agreed’ has meant that votes were rarely called. Indeed, until last year's vote on the harm reduction resolution there had not been a vote on a resolution since the 1980s. This year all seven resolutions were brought to a vote by the US.

Whilst consensus is a superficially attractive idea in international affairs, in practice it gives any Member State or grouping an effective veto, and means that system evolution is almost impossible. Formal normative advice is invariably watered down to achieve consensus - and so defaulting to the status quo. But if there was a desire to break the Vienna consensus to allow for more votes, that could enable an evolutionary modernisation process, no one wished it to happen in the way that it unfolded this year.

Similarly, some critics have seen defunding of many counterproductive UNODC programs as an important step towards more substantive system reform - and will not weep to see the US pull its funds from the failing agency. But again, the problem is the wider context of the US also pulling funds from UN Human Rights Bodies, the WHO, UNAIDS, UNDP and many other UN bodies that are, broadly speaking, forces for good. This isn’t a surgical strike at the UN system, but institutional carpet bombing - with tragic and deadly collateral damage. For international relations analysts it was disconcerting, with years of established norms being incinerated. And again, while many rightly feel evolutionary system change is needed, the bull in a china shop diplomacy on display from the US is unlikely to deliver it. At least when Russia and China were creating problems it was expected, in many ways priced in. There was evidently a plan behind it. By contrast, for the US it felt entirely unstrategic. Where this leaves the UNODC, the CND, and the drug control system more broadly is far from clear. Change is happening, which is good….in theory. But when it is being driven by a morally and strategically unmoored US administration with little or no concern for international law and global governance - we should all be concerned. If the International drug control system is to be remade, it needs to be under the terms of the UN charter, not MAGA idealogues.