10th July 2020

Recent events may look like good news for those who think prohibition can deliver a ‘drug free world’.

Firstly, COVID-19 has meant unparalleled restrictions. For over 3 months, people who use drugs were locked down. With almost no one out on the streets, anyone selling was highly conspicuous. We’ve seen a hike in stop and search, often on the premise of suspected drug possession. At the same time, smuggling opportunities fell with a near halt to international travel.

Has this led to a major disruption of the UK drug market? Perhaps surprisingly, no. The market morphed between drugs in places, with a worrying rise in benzodiazepine use, and some dangerous variability in strength, and some price gouging. But there has been little dramatic change, with a rapid return to normal prices and availability in many places. Perhaps suppliers expect seizures and production problems, so hold stocks high enough to ride them out. And some smuggling routes, for example by post or sea-freight, carried on. Retailers also switched tactics, including dressing as key workers, and expanding door-to-door supply, hidden in the wider increase in home deliveries. The resilience and adaptability of drug markets is well known, but the extent and speed of this response surprised many.

But that’s not all. Last week, news emerged of a huge disruption of criminal activities following the hacking of ‘Encrochat’ phones by European police agencies. The newspapers reported ‘The operation has so far resulted in the arrest of 746 alleged crime bosses’ and seizure of an arsenal of firearms, more than two tonnes of drugs, and £54m. The National Crime Agency (NCA) called it: ‘The biggest and the most significant law enforcement operation of its kind in the UK...previously unmatched in terms of its scale..the breach was like having an inside person in every top organised crime group in the country.’

'Operation Venetic’ was an amazing piece of police work, involving international cooperation, and the most up to date techniques to hack criminal networks’ phones. It was delivered with great professionalism, and no doubt took some very dangerous criminals out of circulation.

So surely now, with perhaps the biggest organised crime group bust in history, coming on top of COVID-19, we can expect a major sustained fall in the scale of the drug market, drug-related violence, drug-related deaths and people being exploited in ‘county lines’ and cannabis farms?

In reality, history tells us it doesn’t, and never will, work like that.

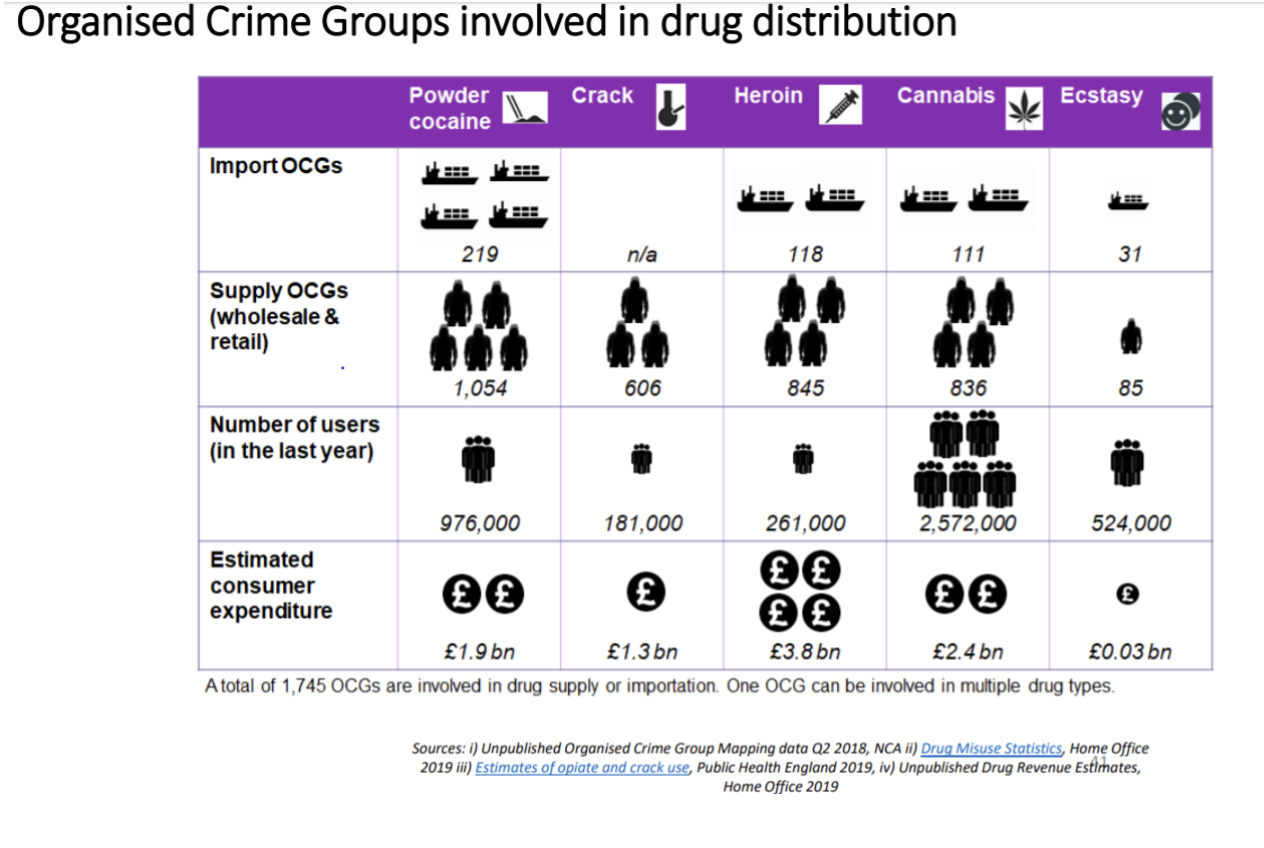

Firstly, the Black Review estimated that there are 1,745 Organised Crime Groups (OCG) involved in importing or supplying drugs in England & Wales alone.

With some individual OCGs suffering many arrests, the total of 746 arrests while very high, means most OCGs have been left untouched, and ready to fight over turf vacated by their opposition, something we have seen many times before around the world.

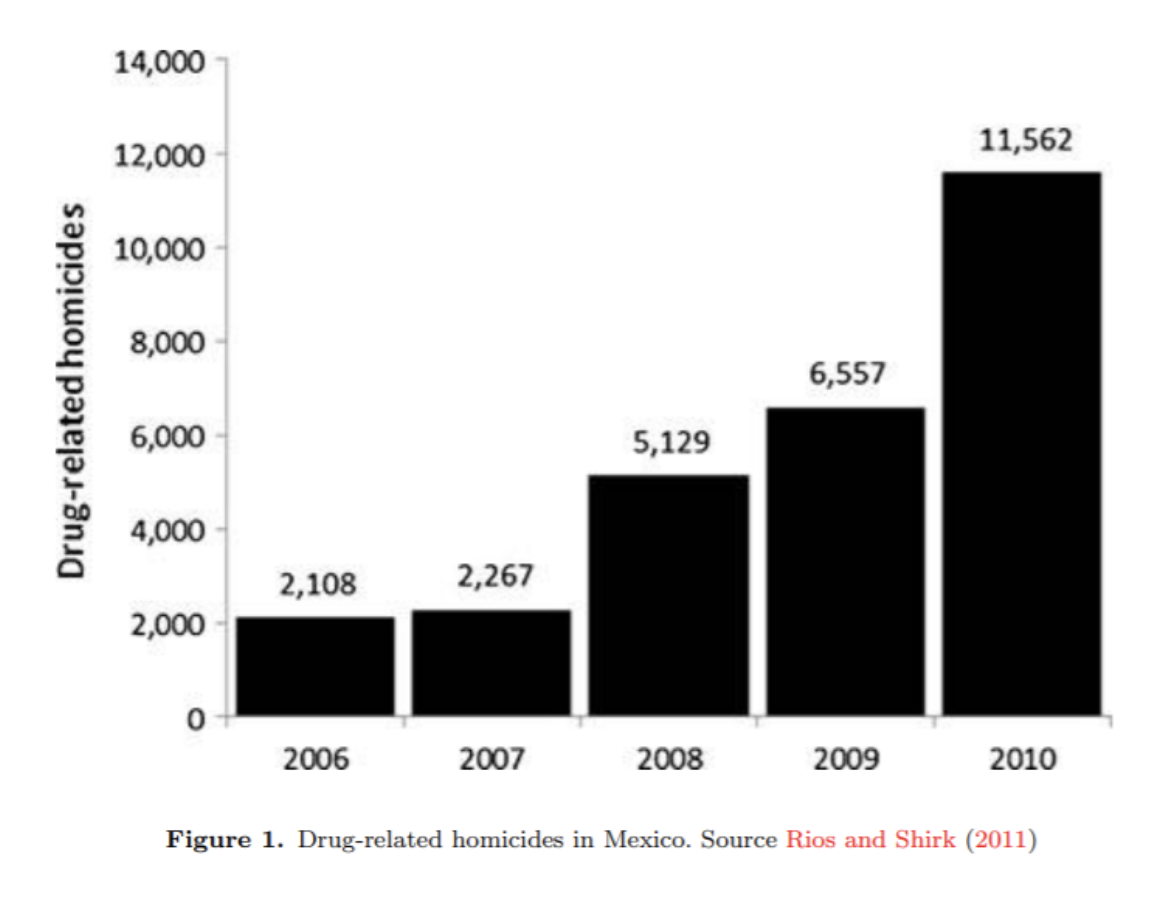

In 2006, for example, the Mexican Government declared war on the drug cartels, saying they would crush them through enforcement. ‘Kingpin’ after ‘kingpin’ was named as public enemy No. 1, whose demise would make all the difference. Only it hasn’t. Instead, drug-related murders in Mexico keep hitting new grisly records, and the cocaine has flowed uninterrupted.

Think that figure of 11,562 murders in 2010 is shocking? There were 33,341 murders in 2018.

As Harvard Academic Viridiana Rios asks and answers in the title of this paper: Why did Mexico become so violent? A self-reinforcing violent equilibrium caused by competition and enforcement.

“Turf wars emerge when monopolistic control of territories by drug-trafficking organizations is broken, when territories become competitive and traffickers fight for them.”

And Mexico is not unique. Research around the globe shows that disrupting drug markets by enforcement increases violence. The story is the same, from increasing murders connected to Copenhagen’s cannabis market, to biker gangs fighting over Canada's cocaine trade. The UK Government acknowledged this in its own evaluation of its 2010-16 Drug Strategy, stating that ‘it is widely acknowledged that violence is an unintended consequence of enforcing drug laws ... For example, violent conflict may result between a dealer displaced by law enforcement and an established dealer’. A recent Home Office report on homicide made the same point, observing ‘strong evidence that disruption in illicit markets can drive homicide trends’.

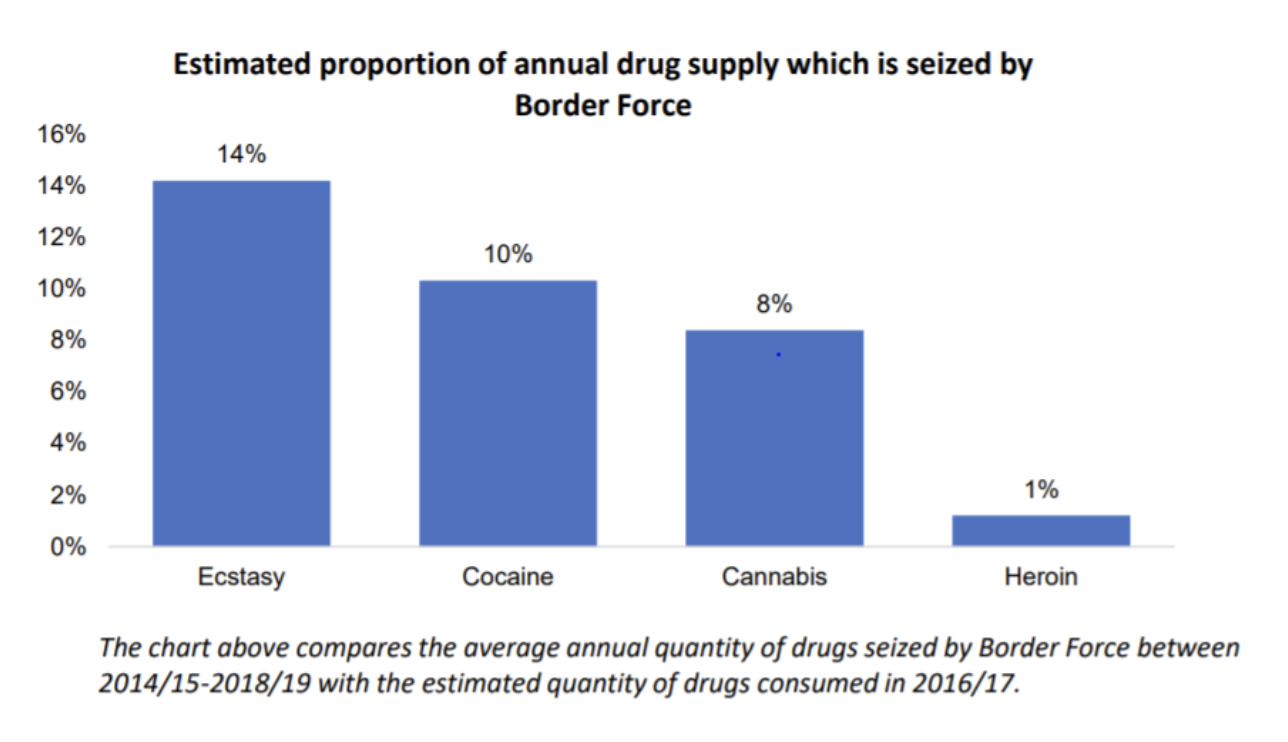

Just as arrests don’t stop new criminals taking over markets, seizures do not push organised crime groups out of the drugs trade either. In 2003, the Prime Minister’s Strategy Unit estimated that because profit levels are so high, removing organised criminals from the UK drug trade would require consistent seizure rates of 60-80%. The Black Review estimated that 10% of cocaine, and just 1% of heroin is seized by the UK Border Force, and that even large seizures are an affordable cost of business. In fact, they are a far lower burden than the combined legal tax rates and product losses (supermarkets waste 2% of food, fresh fish retailers 5% of products) normal businesses face, on far less profitable commodities.

In a high-profit market, criminal entrepreneurs always find ways to meet demand. The UK Government’s evaluation of its 2010-16 Drug Strategy acknowledges this:

‘some enforcement activities can contribute to the disruption of drug markets…but the effects tend to be short-lived.[…] illicit drug markets are resilient and can quickly adapt to even significant drug and asset seizures.’

The UN System Coordination Task Team of the UN Chief Executive Board (representing all 31 UN agencies, chaired by the Secretary General) concluded that ‘The assumption that tougher law enforcement results in higher drug prices and therefore lowers the availability of drugs in the market is not supported by the empirical evidence.’ A particularly dramatic example of this was when the Taliban reduced Afghan opium production by 90% in 2000-01. Yet this had little effect on the retail heroin market, anymore than the US-led invasion of Afghanistan did.

In short, police are in an impossible position - they are required to intervene especially where there is clear evidence that major crimes are about to be committed. But when they do act, they often exacerbate the situation. This is not their fault. Responsibility for our enforcement led approach lies with successive governments refusing to bite the bullet, and deliver the comprehensive reforms needed. Only reducing demand for illegal drugs will squeeze organised crime group involvement down to a fraction of the market, and this has to be done in three ways together - none of which alone will suffice.

It is time to legally regulate drugs, to take most of the market from organised criminals. We must properly fund treatment and expand innovative approaches (including heroin prescribing clinics, Police Diversion Schemes and Overdose Prevention Centres) - because people in treatment take fewer illegal drugs. And of course, treat those who have drug dependency issues as human beings and give them the mental health, housing, financial and other support they need to deal with the reasons they are using drugs in the first place.

As Vince O’Brien, NCA Drugs Lead said last year:

‘We can’t arrest our way out of [ongoing drug demand and supply] anymore than we can arrest our way out of serious violence. We need to tackle the drivers behind it.’

What we mustn’t do is let eye-catching seizures and arrests blind us to the fact that enforcement cannot solve our ‘drug problem’, and often makes things worse.

Author: Martin Powell, Head of Partnerships at Transform Drug Policy Foundation