16th January 2019

The question of how we should regulate a legal market in stimulant drugs, including cocaine, MDMA and amphetamines, remains one of the most unexplored challenges in contemporary drugs policy. It is a void Transform’s upcoming book on stimulant regulation aims to fill.

There’s been enormous progress in the debate around the legalisation and regulation of drugs in the past few years. Most obviously the wave of cannabis reforms across the Americas – (Uruguay, 10 US states, Canada, Jamaica, and now Mexico), and now across the globe with reforms imminent in much of Europe, New Zealand, South Africa and elsewhere.

At the other end of the risk spectrum we have also seen the growth of maintenance prescribing models for injectable heroin to people who are dependent on it. As a medical intervention this form of treatment is not technically ‘legalisation’ (it’s already legal). However, if you were previously buying heroin from a street dealer, and are now receiving it on prescription, your use and supply have effectively been ‘legalised’.

So at either end of the risk spectrum, with cannabis and heroin we have two, albeit very different, models of legal drugs regulation in action. This demonstrates how a move from criminal controlled to legally regulated drug markets can improve health and community safety outcomes and better protect vulnerable people – for less money.

Between these poles sits the array of stimulant drugs. This group of drugs includes substances of widely varying risks, which are associated with widely varying risk behaviours and using motivations. For example, drinking coca or ephedra tea daily is very different from smoking crack or methamphetamine daily. But what they do have in common is that they are often neglected in the drug policy discourse – often lost in the shadows between the twin spotlights of cannabis reforms and the opioid crisis.

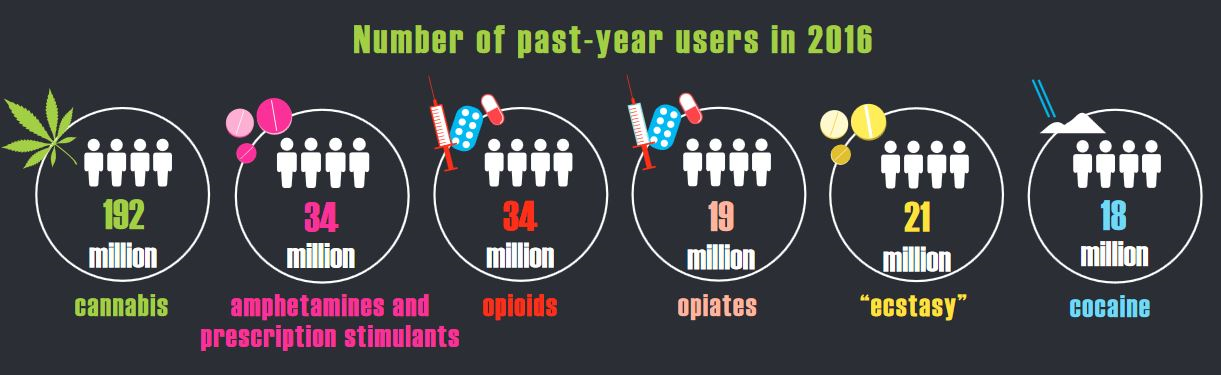

Yet stimulants are increasingly widely used, and production is expanding to meet the growing demand. The latest UNODC global data suggests that (probably conservatively) in 2016 there were 34 million amphetamine users, 21 million ecstasy users, and 18 million cocaine users. The health risks people who use stimulants face appear to be increasing – with increasingly potent MDMA and cocaine, ongoing risks from adulterants (now including fentanyl), and a complete lack of information about either strength or purity to inform safer using decisions. In the UK, between 2016 and 2017, the number of cocaine-related deaths increased for the sixth year running, from 371 to 432 – a figure more than double that of a decade ago when use was at a similar level. In the US, stimulant deaths increased by 33% between 2015-16 – also reaching record levels.

So production is up, use is up and negative health consequences of use are up too. For a policy that promised ‘a drug free world’ it is a spectacular and ever more expensive failure. And this is before we even factor in the harms of the illegal trade: the horrific violence in Mexico, civil wars and displaced communities in Colombia, the destabilisation of West African transit countries, street crime in urban centres across the globe.

Prohibition works well for cartels, and it works well for certain politicians – as a form of social control, as an expression of xenophobic attitudes, as cover for other geopolitical agendas, or as an opportunity for some macho drug war posturing. But for people around the world who use illegal stimulants and the communities they live in, it has been an unmitigated disaster.

The same pragmatic regulatory logic of risk management that applies, in different ways, to cannabis and heroin (and indeed to alcohol and nicotine) now needs to be applied to stimulants, specifically including cocaine, MDMA and amphetamines (and other drugs – including psychedelics – but that’s potentially our next book!).

Which products should be made available? Who would sell, dispense and prescribe them, and where? Who has access to the market? Where, how, and by whom would they be produced? How do we apply the range of regulatory tools available post-legalisation to different stimulants to better meet our shared public health and community safety goals? This is not about encouraging drug use, it is about our responsibility for managing the reality of drugs – including drugs more risky than cannabis.< /p>

These are precisely the questions that Transform’s work has focused on over the past two decades – including in our groundbreaking ‘Blueprint for Regulation’ in 2009, and our cannabis regulation guide from 2013, which has gone on to influence reforming governments in Uruguay, Canada and elsewhere.

Criticising the failures of the war on drugs is important, but not enough. We need a coherent and credible vision of how an alternative regulatory policy will work after the war on drugs: one that the public can buy into when they see the harms it can reduce and the benefits it can bring. And one that policy makers can present as the foundation for a long overdue adult discussion on how the post-drug war peace will function. Transform’s Blueprint for Regulation contained the first exploration of the challenges and options for regulating different drugs, including stimulants. Our new book builds on this work – providing a more detailed policy analysis and model regulatory frameworks for policy makers and reform advocates as we move forward in the new regulation era. Fifty years of prohibition has failed. Stimulant markets aren't going to disappear, so we have have to decide who will be in control: Governments or gangsters? This book will show how taking control can work in practice.

Our crowdfunder is now closed. Thank you to the 150+ people who donated to make our upcoming stimulants regulation guide a reality. You can still donate directly to Transform here: https://transformdrugs.org/donate/