12th August 2022

This week Colombia’s new President, Gustavo Petro, called for an end to the drug war. During his swearing-in, he declared “It’s time for a new international convention that accepts that the war on drugs has failed”. This is a momentous statement by the political leader of a country that has been embroiled in a violent drug war for the last 50 years. As Colombia looks forward to a future without prohibition, we revisit the time our colleagues spent in Colombia earlier this year, talking to local Colombians about how legal regulation of coca and cocaine could work. This trip was a part of our launch of the Spanish version of 'How to Regulate Stimulants'.

Almost a century of evidence demonstrates that punitive, enforcement-led approaches to drugs have failed everywhere they have been tried. Prohibition and criminalisation were supposed to eradicate drug markets, deter people from using drugs, prevent harm and protect people – but they have done the opposite of that. Today, despite ballooning drug enforcement budgets, expanding drug markets serve rising demand, empowering and enriching increasingly sophisticated organised crime groups, while millions of users and small-scale market actors – mostly from socially and economically marginalised communities – are criminalised and imprisoned, and drug-war related violence continues to escalate.

Colombia has been at the epicenter of the global drug war since the 1970s. On the one hand, illegal drug profits have helped to sustain the armed conflict, but it has also become a means of survival for many rural farmers. In response, militarised counter-narcotics operations, including aerial fumigations, have had devastating consequences for coca-farmers and local people – while utterly failing to curtail the global trade.

Crisis can often be a driver of reform. In the UK and much of Europe and North America, the alarming number of drug-related deaths are driving recent debates around innovative new policy harm reduction approaches, including legal reforms that can facilitate ‘safe supply’. In Colombia, and much of Latin America, while public health questions remain important, it is security crises that are forcing the reform debate up the agenda.

Colombian activists, academics, politicians and communities affected by the illegal drugs trade and efforts to eradicate it are now challenging one of the last drug policy taboos, by advancing the debate about coca and cocaine regulation. Most notably a coca and cocaine regulation Bill was tabled and discussed in the Colombian senate last year. Despite opposition, this was an important and historic step forwards; as Transform noted, “in practical terms [the proposed bill] serves to help normalise the discussion around responsible regulation of drugs (other than cannabis) within the mainstream political debate; in Colombia, in Latin America, and the wider world. It makes meaningful public engagement and advocacy on this issue much easier.”

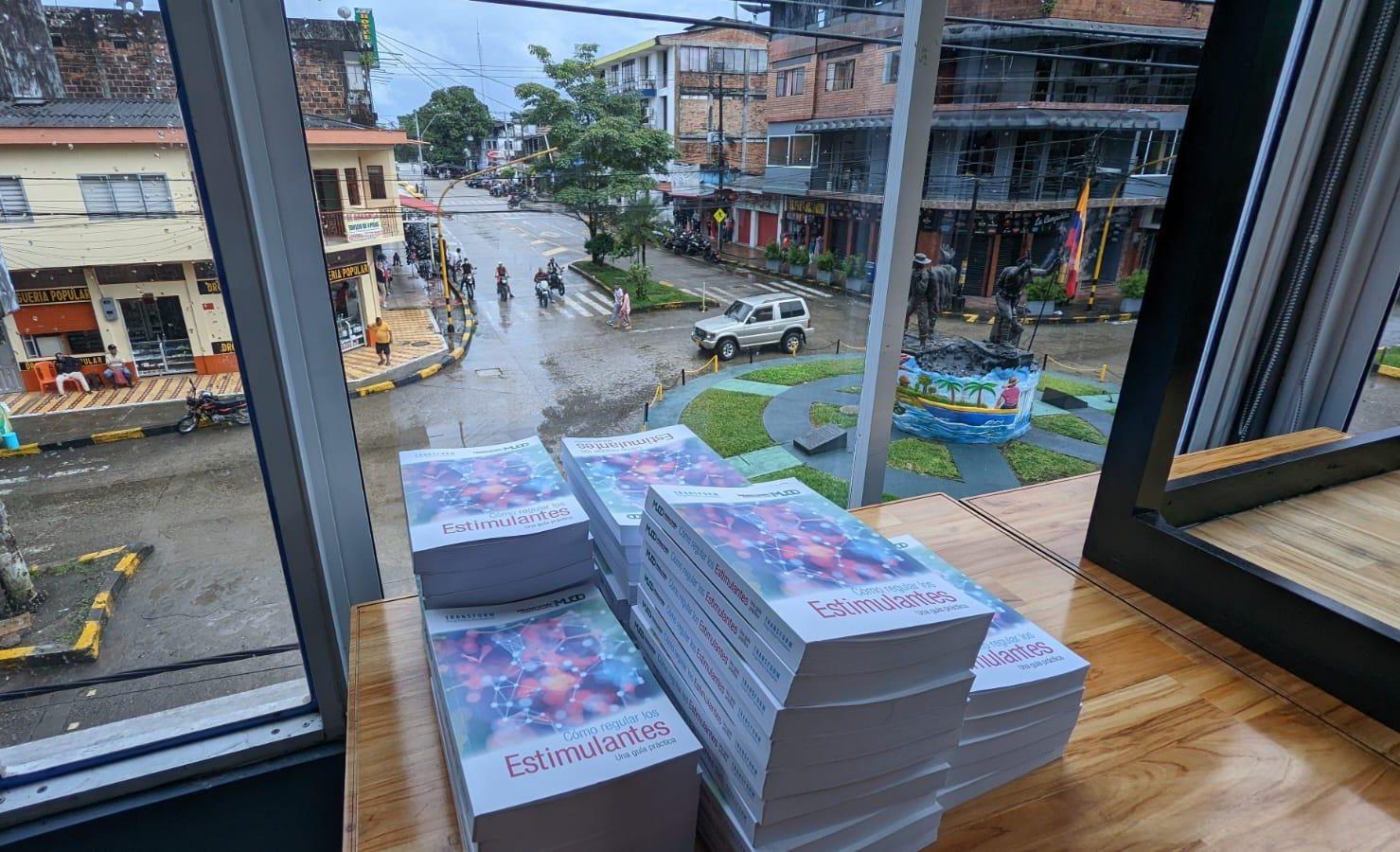

We were fortunate to have the opportunity to travel to Colombia earlier this month to launch the Spanish version of ‘How to Regulate Stimulants: A Practical Guide’. As well as presenting the ideas and proposals in the book, we were able to discuss the practical details of a regulatory framework for a coca and cocaine market with key stakeholders and allies leading the Colombia’s coca/cocaine policy reform movement, and to learn from the inspiring creative work and resilience of activists living and working on the frontline of the drug war.

Transform’s Anyone’s Child campaign seeks to accelerate public understanding of the failure of our current drug laws and the potential benefits of reform by sharing the real life stories of families impacted by the drug war in the UK, and around the world. The campaign emphasises the importance of working together with the communities most impacted by prohibition in the design, implementation and evaluation of new legislation and regulatory models. This was a dominant theme in our conversations with communities across Colombia. We had the privilege of exploring the opportunities and challenges of coca and cocaine regulation with social leaders, coca growers and people from indigenous communities – in Puerto Asís, in the southern department of Putumayo which borders Ecuador; in Tumaco, Nariño, on the Pacific coast; and in Cali, a city in the Valle de Cauca department. Indigenous people already have collective rights to legally grow and use coca in Colombia (even if nominally illegal under the UN drug conventions), based on the recognition of the traditional and sacramental use of the plant.

We shared the regulated production and retail model proposed in Transform’s stimulant book – a three-tiered system whereby the riskier a product or preparation, the stricter the controls over its production, supply and use are justified – and we asked how this model might address some of the local challenges generated by the drug war. The proposal lays the groundwork for what the legal market would look like from farming to consumption, drawing on practical experience from legally regulated markets for alcohol, tobacco, pharmaceutical drugs and, more recently, cannabis. It envisages a light touch regulatory approach to coca leaf and lightly processed products (similar to coffee, for example), strictly regulated pharmacy-type sales of unbranded cocaine powder for adult personal use, and a decriminalisation and harm reduction approach (but not a retail model) for smokable crack/basuco/paste base. Nevertheless, specific regional needs and realities in Colombia coupled with the unique regulatory challenges posed by cocaine regulation require local knowledge and actors to lead the process, and ensure that social justice and sustainable development are specifically built in.

We imagined what legal regulation of coca and cocaine production and processing might look like, and asked how we can ensure that new legal markets would truly benefit the communities disproportionately impacted by law enforcement under prohibition? This includes exploring the options such as licensed growers, farmers unions and cooperatives for transitioning illegal market participants into legal production. People asked how a regulated cocaine market might contribute to sustainable incomes and inclusive economic growth, empower women, protect children, and promote responsible environmental stewardship. On this later point, people suggested we need to expand our understanding of harm reduction beyond public health, and apply it to environmental and social harms.

Historic state abandonment underlies much of the Colombian armed conflict. Outside of cities and towns, in rural areas with illegal crops, the government has been almost completely absent: often the only state representatives people come into contact with are members of the armed forces. State non-compliance with the 2016 peace agreement has deteriorated the economic situation of many families who signed up to the crop substitution programme and increased scepticism and distrust in the national government. Consequently, people raised legitimate and well-founded concerns about the state’s capacity to facilitate a peaceful transition to a legal market and to effectively regulate a legal cocaine market. Nevertheless, if social equity and inclusion principles are implemented which honor and prioritise the interests of small-scale, economically vulnerable farmers, coca and cocaine markets could be transformed into a potential driver of regenerative, sustainable and social development. In doing so, coca and cocaine regulation could also be a form of long-overdue reparations for ethnic and small farmer communities.

More thinking and collaboration on these issues needs to be done, but it was really promising to hear conversations moving on from whether or not drugs like cocaine should be regulated, to discussing the details of how production, supply and use should and could occur within local political environments and legal frameworks. Populist ‘tough on drugs’ narratives (see, for example, the absurd recent ‘crackdowns on middle class cocaine users’) can obscure the reality that drug policies, illegal drug markets, and the reform debate are interconnected and global. It was humbling and inspiring to explore together how drug policy reform can better serve the interests of the communities that suffer most from prohibition, whether they are the families of people who use drugs in Europe or coca growers in Colombia, among many others. Huge thanks to MUCD for co-producing and translating ‘How to Regulate Stimulants; A Practical Guide’, to FESCOL for supporting the publication and its dissemination, and to ATS and VIsoMutop for organising and coordinating the events so brilliantly.

Read more about cocaine regulation in Colombia here: Historic win for coca/cocaine regulation Bill in Colombian Senate

This blog was written by Mary Ryder. Mary works on the Anyone’s Child Campaign and is also a PhD student in Security, Conflict and Human Rights. Her research focuses on drug policy and transitional justice in Colombia.