21st April 2022

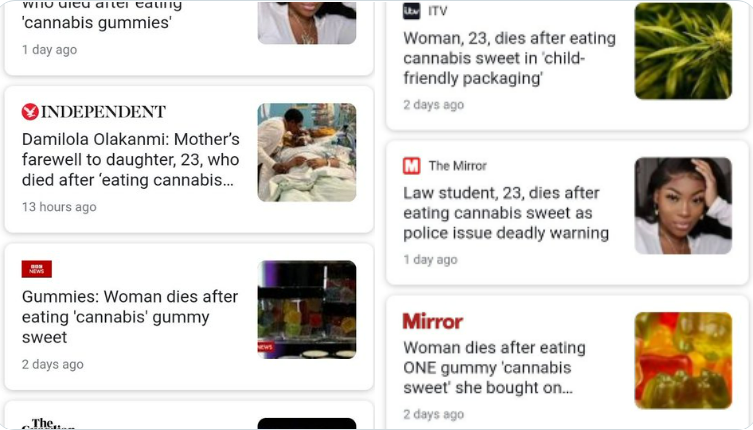

Earlier this month there was widespread coverage of the tragic death of Damilola Olakanmi, following consumption of what was bought as a 'cannabis gummie', but what police reports indicate was actually infused with a synthetic cannabinoid. Media headlines, following the lead of the Met Police press release, unhelpfully implied the death was cannabis related - when the story details reveal this appears to be a poisoning death - synthetic cannabinoid mis-sold as a cannabis product.

The tragedy highlights the risks implicit in unregulated illegal drug markets absent quality controls and vendor accountability - but also the challenges that synthetic cannabinoids raise as we move into an era of increasingly widespread cannabis regulation. Below is the section on synthetic cannabinoids from Transform's newly updated 3rd edition of 'How to Regulate Cannabis: A Practical Guide' available to buy for only £15 here, or read online for free.

Recent years have seen a significant growth in the manufacture, sale and use of products containing synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists more commonly known as ‘synthetic cannabinoids’. These represent ‘the largest group of substances currently monitored by the EU Early Warning System’, with a total of 169 synthetic cannabinoids being identified between 2008 and 2016. Synthetic cannabinoid products emerged as alternatives to traditional cannabis, intended to mimic its effects. Typically sprayed onto a smokable herbal mixture, synthetic cannabinoids are functionally similar to the active ingredient of cannabis, THC, binding to the same cannabinoid receptors in the brain.

Synthetic cannabinoids such as JWH-018, JWH-073 and CP47,497-C6 are the active ingredients of many products marketed under more consumer-friendly names such as ‘Spice’ and ‘K-2’. The increase in the variety and popularity of such products in the early 2010s was mostly attributable to their existence as a legal alternative to cannabis that was easily available (yet subject to virtually no regulatory control) via online and high-street retailers.

While many synthetic cannabinoids have now been prohibited under the UN drug conventions, the volume and rapid emergence of new variants means it has been impossible for drug control bodies to keep up. Many synthetic cannabinoids have also been prohibited under national drug control legislation. In some cases, such as in the UK, Poland, and Ireland, a ‘catch-all’ blanket ban on any psychoactive substance has been implemented in an attempt to avoid successive bans being thwarted by new variants.

Risk profile

While there is an established body of knowledge regarding the pharmacology and toxicology of cannabis and THC, there is significantly less similar information about synthetic cannabinoids or the products that contain them. Only a few formal human studies have been published, although there is strong evidence to suggest that synthetic cannabinoids are riskier than cannabis/THC. A 2019 review acknowledged that synthetic cannabinoids ‘can be more potent at the cannabinoid receptors and in turn have greater toxicities’. This, combined with the considerable variability of synthetic cannabinoid products, both in terms of the type and quantity of substances present, means there is a considerably higher potential for overdose and acute adverse events than with cannabis. Different synthetic cannabinoids also have different risk profiles so generalisations become more problematic.

Prevalence of use

The relative paucity of information on synthetic cannabinoids extends to levels of use. The limited amount of survey data available, however, suggests that in most countries, particularly those in Europe, prevalence of synthetic cannabinoid use is very low. The exception is the US, where at least among young people, prevalence appears to be relatively high (although declining). In the 2020 US Monitoring the Future survey of students, last year prevalence of use for 17- to 18-year-olds was recorded at 2.4%, down from 5.8% in2014, 7.9% in 2013 and 11.3% in 2012. In contrast, in the UK, the Crime Survey for England and Wales covering 2014/2015 found a total of 0.9% of adults (16–59) had used NPS in the last year, of which 61% had used synthetic cannabinoids. By 2018/2019, only 0.5% of adults reported using NPSs, including synthetic cannabinoids, in the past year. Most individuals strongly prefer natural cannabis to synthetic cannabinoids, with the former described as producing more pleasant effects and the latter associated with more negative effects. Synthetic cannabinoids have, however, now established a market amongst some more vulnerable and economically marginalised populations of people engaged in high risk or dependent drug use, for whom they can now offer a potent and relatively inexpensive alternative to other available drugs.

Regulatory response

Many synthetic cannabinoids are currently banned under domestic drug laws, and under a system of legal cannabis regulation their legal status would not automatically change. In fact, we recommend that within a legal regulatory framework to control cannabis, no new, functionally similar synthetic substance would be made legally available for retail. While it seems unlikely, if specific synthetic cannabinoid products can subsequently demonstrate a level of risk equal to or less than that of traditional cannabis products, regulators could re-evaluate this position and potentially make these specific products available for retail — under strict regulatory requirements.

While all penalties for the possession and use of such products would be removed, proportionate penalties for unauthorised production or supply would still be enforced. Given cannabis would be made available through a legally regulated market, a default prohibition on the production or retail supply of any synthetic cannabinoid products is justified. Use of synthetic cannabinoids would instead be managed through a harm reduction model, as envisaged for higher risk stimulant preparations and outlined in Transform’s 2020 book, How to regulate stimulants: a practical guide.

A regulatory system has been been developed in New Zealand, under which the manufacturers of novel psychoactive substances including synthetic cannabinoids can — in theory at least — legally sell them under strict conditions if they are able to demonstrate that they meet specified low risk criteria. The aim of such regulation is to protect people who use drugs by guiding them towards safer products whose risks have been properly established, a concept that developed from earlier efforts to regulate a synthetic stimulant, BZP. However, while this regulatory system remains technically in place, it has run into political opposition and a number of technical challenges — crucially, how to establish ‘low-risk’ harm thresholds without using animal testing (which is specifically prohibited).

So, while New Zealand is the only country in the world with a comprehensive piece of legislation for regulating NPS for nonmedical use in theory (with certain synthetic cannabinoids seen as the most likely first candidates for consideration), in practice no NPS are currently regulated under the system.

Although New Zealand has attempted to develop a pragmatic approach to dealing with existing synthetic cannabinoid demand and established markets, the need for such regulated supply will naturally diminish once cannabis has been made legally available. Demand for synthetic cannabis is already relatively low and would only shrink further: consumers would have little incentive to buy synthetic cannabis when they can legally purchase the real thing.

Remaining challenges are likely to include use in prisons and for people on probation subject to testing (as synthetic cannabinoids are not consistently identified by conventional testing regimes), and for the small population of people with heavy or dependent patterns of use who are not interested in substituting back to cannabis. A dedicated harm reduction model targeting problematic or high risk use, including among people who are homeless, will help reduce these harms while synthetic cannabinoid use naturally falls over time.

Crucially, it is important to acknowledge the role of the current prohibitionist legal environment in driving the emergence of synthetic cannabinoids and other NPS in the first place. From the outset, the key attraction of synthetic cannabinoids was their legal status — which gave them a competitive advantage over traditional cannabis — rather than their effects per se. It is notable, for example, that no significant market for synthetic cannabinoids emerged in the Netherlands, where there is de facto legal cannabis availability.

The inevitable bans of synthetic cannabinoids only fueled the emergence of even more, often more risky, products with minor molecular variations. More comprehensive ‘crackdowns’ or blanket NPS bans may have arguably had the positive impact of pivoting some current or potential consumers back towards less risky traditional cannabis — even if this was not what those implementing the bans intended. But even if the synthetic cannabinoids market now contracts (whether through prohibitions or due to a legal regulated cannabis availability), cannabis prohibition has unleashed more than 100 risky synthetic cannabis mimics into the market, and the entrenchment of their problematic use amongst key vulnerable populations suggests that there is no easy solution.

Header image: wikicommons

The newly updated 3rd edition of 'How to Regulate Cannabis: A Practical Guide' is out now! You can purchase the hard copy for only £15 or access online for free.