28th July 2022

Compared to cannabis, the public debate around the legal regulation of stimulants has been restrained in most parts of the world. It’s not hard to see why. Cannabis has tended to dominate public debate; as the most used illegal drug, one that is very easy to produce and procure, and also one associated with lower risks relative to most other drugs, it has, unsurprisingly, been at the forefront of reform efforts around the world.

The more dangerous and threatening a drug is perceived to be, the harder it becomes to make the case for regulation, even if - as Transform has long argued - greater risks are precisely the reason why regulation is needed, not a reason to maintain prohibitions that only increase them further.

The exception to this pattern is when legal drug supply moves within the medical sphere, namely the prescription of substitute drugs as part of a harm reduction approach for people with drug dependencies. Here we can already witness wide public acceptance of the legal supply of some of the most historically feared and demonised drugs, including methamphetamine and injectable heroin.

While legal cannabis and prescribed heroin could hardly be more different - what they have in common in the public debate is familiarity. People have seen that the cannabis coffee shops in the Netherlands, and cannabis stores in Canada for example, look very similar to bars and off licences. And they are familiar with prescribing and supervised-use of risky drugs in pharmacies and clinics. These supply models are known, understood - and correspondingly less threatening and easier to discuss and advocate for.

But for the significant number of drugs that sit somewhere in the middle of the risk spectrum, particularly stimulants used in social settings, there are few reference points for how legal regulation would work. They are drugs perceived as much more risky than cannabis, but are also associated with hedonism and indulgence - so cannot be shoehorned into a medical supply model for people with drug dependencies who naturally engender a far greater degree of public sympathy.

It was, therefore, one of the key goals of Transform’s recently published stimulant regulation guide, to move the debate forward by increasing understanding of how stimulants could be made legally available in the future. Even as we now have a growing consensus that the war on drugs has been a disastrous generational failure - the debate will struggle to move further without a clear vision of what comes after prohibition. So the idea was to present and familiarise people with models of responsible regulation of stimulant products, vendors, outlets, availability and marketing. Models that people could understand, find credible and buy into. But you can only achieve so much in print….

So it has been brilliant to see our colleagues from Dutch harm reduction service Mainliners take this debate into the real world with the world’s first pop-up model MDMA shop, in the heart of Utrecht.

The idea behind the installation (part of their much bigger Poppi drugsmuseum project) was to move beyond just asking if we should regulate MDMA, but how we should do it - by presenting 3 different retail MDMA models to the public and gauging their reactions.

Commercialised Retail Model

The first model resembles an over-the-top candy store, with a rainbow of wall-mounted pill dispensers, in-your-face visual promos, and your pill (in this case just a breath mint) delivered via a gumball-type dispenser once you have filled in a short iPad questionnaire.

Nightclub Retail Model

The second model is a similarly low threshold retail model in a mock-up nightclub in the store’s basement. As with the candy store model - a short iPad questionnaire gives you a coin which you can then use in a dispensing machine (an adapted nightclub condom dispenser) with 3 different pill options of varying potency. When you pull out the draw the sound system beats drop and you are illuminated with a light show.

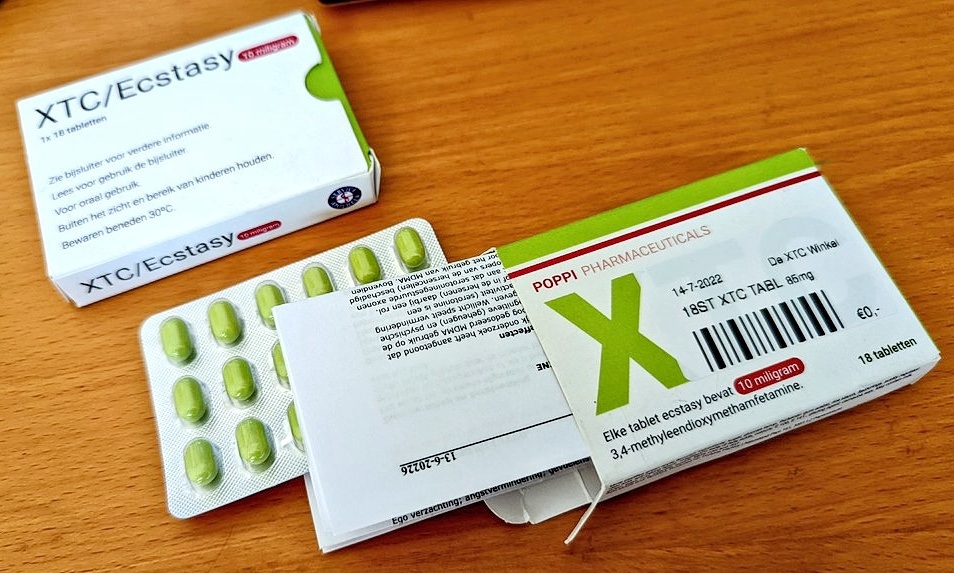

Pharmacy-Style Retail Model

Finally, there is a pharmacy-style retail model - loosely adapted from the proposals in Transform’s stimulant regulation guide. Rather than the vulgar marketing of the candy store, it adopts the more minimalist clinical feel of a pharmacy - the only decor being shelves of the product itself in unbranded pharmaceutical packaging (and even this would likely not feature in a real-world model which would, if anything, be even more plain and functional). Acquiring the MDMA requires filling out a more detailed iPad questionnaire - each question introduced with a short video from a health professional - that serves to educate about risks and harm reduction, and also ascertain personal information including weight, potential health vulnerabilities, and experience of use. This information is then used to provide a bespoke label with dosage information and a personalised barcode on the packaging that is dispensed as the questionnaire is finalised. In the future this interaction would replace the iPad with a licensed vendor, trained to offer tailored support and harm reduction information to each customer.

The whole experience is fascinating and immediately engaging for the public, politicians and media alike, regardless of whether they had any personal interest in using MDMA. From the opening day, it was clear that the candy store and nightclub models, while eye-catching and Instagram-worthy, primarily serve to demonstrate the risks of poor regulation, with people inevitably gravitating towards the obviously more sensible pharmacy model. It is an important message; drugs are not conventional consumer goods and retail regulation needs to reflect and manage the unique risks they present. Conventional commercial retailing is entirely inappropriate for a model that seeks to achieve functional availability without active promotion, guided by public health and harm reduction principles, rather than maximisation of sales and profits.

It would be great to see something similar to this groundbreaking installation in the UK, and elsewhere, but it makes perfect sense that it should be launched in the Netherlands. They have had the cannabis coffee shop for decades, helping to normalise the idea of legally regulated drug availability beyond alcohol and tobacco. They also have a long history of progressive harm reduction with, for example, long-established (and state-funded) drug checking services, similar to those provided by The Loop but operating within a much more pragmatic and supportive political and institutional framework. Compared to the UK, MDMA-related deaths in the Netherlands are very low, and at festivals and events, vanishingly rare; highlighting again how the legal and policy environment is a key factor in shaping drug-related risks.

But the Netherlands also has unique issues relating to MDMA that have driven the debate on regulation forward. A significant proportion of global illegal MDMA production is thought to take place in the Netherlands and has been associated with destructive organised crime activity, including high-profile dumping of toxic waste from MDMA production in waterways and national parks.

These factors have led one of the parties in the Government coalition, D66, to adopt MDMA regulation as part of its drug policy platform. And while they are a minority partner in Government and can’t push through the reform alone - their 24 seats, along with the Green party (supporting MDMA regulation but not in the coalition) with 8 seats, represents an influential block in the 150-seat parliament. D66 notably also hold the positions of deputy prime minister and minister of health. Interestingly, D66 are the majority party in the Amsterdam municipal government, which does have an MDMA regulation platform, although is unable to take it forward without the authorisation of the central government.

Recent academic work exploring optimised MDMA regulation models, and a report advocating MDMA regulation from influential centre-right think tank DenkWerk, have only pushed the debate further into the mainstream.

The timely arrival of the Mainline MDMA shop - makes a breakthrough in stimulant regulation more likely - informing the already vibrant debate and bringing the day when a real MDMA shop will open (using the pharmacy model) closer still.

The model XTC shop is open every day from 1 PM in central Utrecht (a 30-minute train from Amsterdam central), until September 29th. Get more details on the Poppi drugs-museum page.