24th August 2019

Summary

- A fair, healthy Scotland cannot exist with the highest drug-related death rates in Europe, and outbreaks of HIV infection within its most vulnerable communities. The UK and Scottish Governments should work together to:

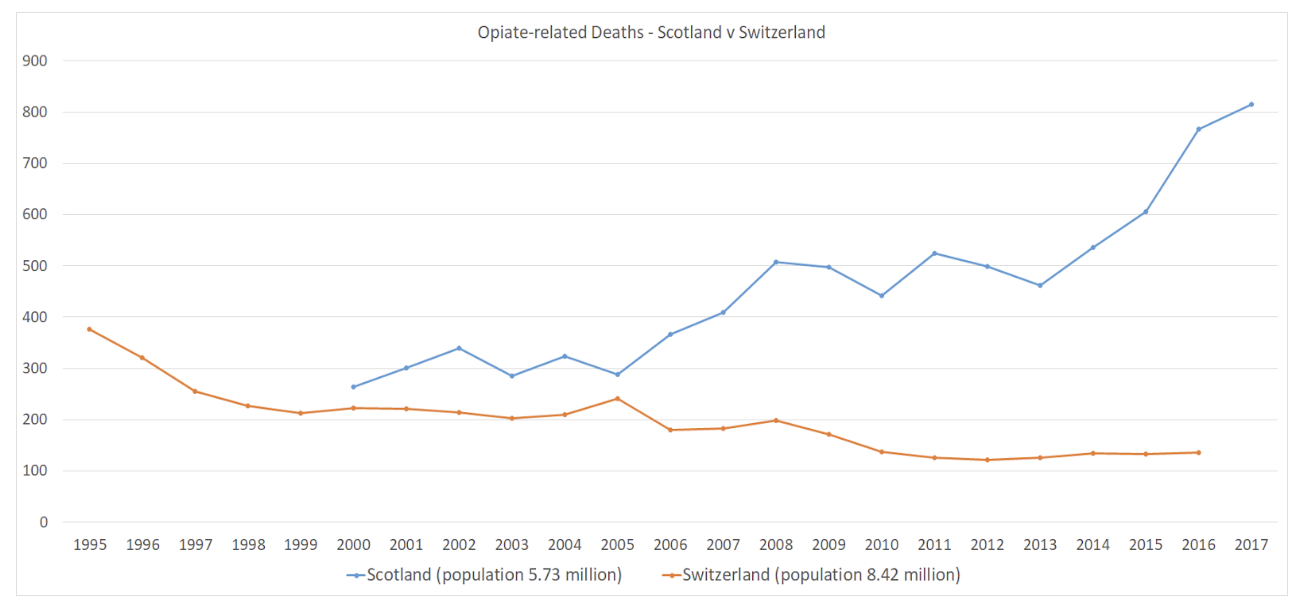

- Treat drugs as a health not a criminal justice issue, using evidence-based interventions, tailored to the local situation. Doing so could replicate the dramatic falls in drug-related harms seen in Portugal and Switzerland.

- Fully fund treatment, including OST, with wrap-around care to build social assets and psychological resilience.

- Decriminalise people who use drugs, reducing stigma and releasing resources to expand harm reduction interventions including Supervised Drug Consumption Rooms.

- Explore options for the regulation of some currently prohibited drugs.

- Devolve powers under the Misuse of Drugs Act to Scotland either permanently or through temporary special powers, such as by declaring a National Health Emergency, unless the UK Government makes this unnecessary by ending the current enforcement-led approach across the UK.

Introduction

Developing effective responses to drug-related health harms requires a public health approach. This means identifying the nature and scope of the problem, understanding the structural drivers that shape risk and vulnerability, and tailoring interventions to target risk and protective factors. As a result of taking this approach to legal drug policy, Scotland has a strong record of leading the way on innovative reforms - including banning smoking in enclosed public places before the rest of the UK, and introducing Minimum Unit Pricing for alcohol against considerable resistance. Similarly, Scotland has taken a public health approach to crime, and violence in particular, that is drawing attention from the rest of the UK and beyond.1

Scotland now needs to extend an innovative, health-led approach to illegal drug policy.

Health harms from drug use in Scotland - a country in crisis

England, Wales and Northern Ireland have seen near record levels of drug related deaths for five years in a row.2,3 Around a third of all drug deaths in Europe occur in the UK.4

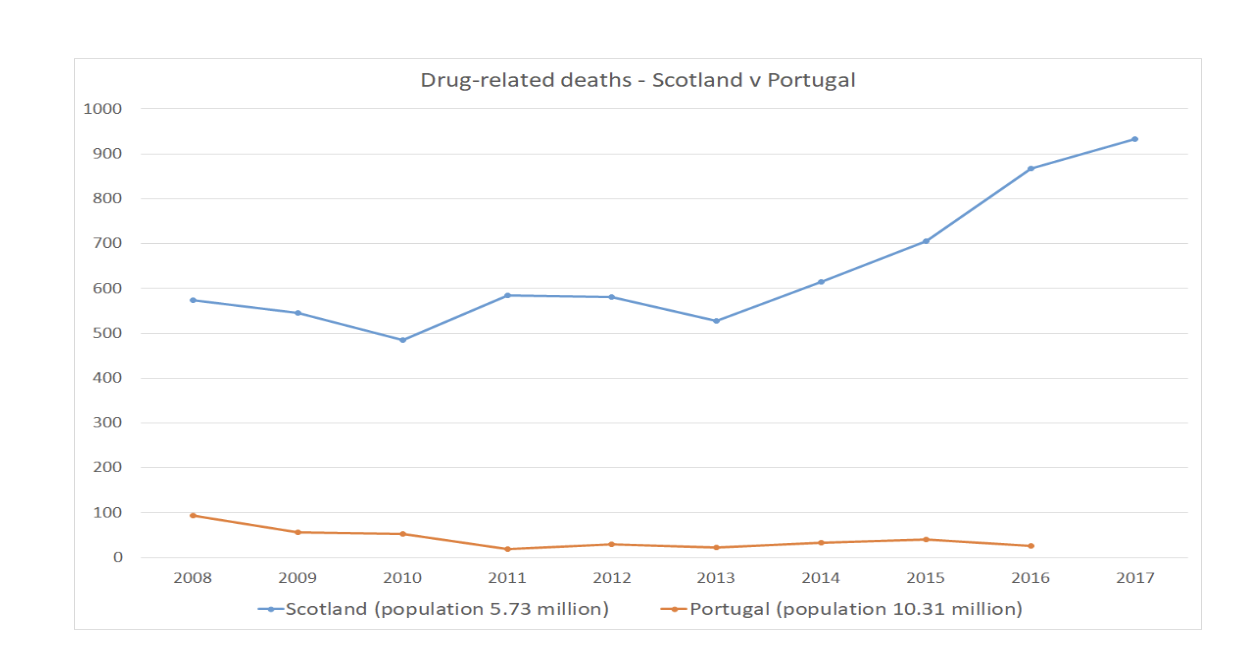

But Scotland’s record drug-related death rates are around two and a half times higher than the UK as a whole.5 On average, between 2013 and 2017, 140 deaths per million population were linked to drug use.6 The 2017 figure (934 deaths), was 170 deaths per million, more than double the 455 who died in 2007.7

Increased drug death rates are often blamed on an aging drug-using population. But other European countries have the same demographics, and problems with deprivation and austerity, yet Scotland has the highest drug-related death rate in Europe.8 According to the European Monitoring Centre on Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), drug-related death rates for 15-64 year-olds in Scotland were 175 per million in 2015, followed by Estonia (132 deaths per million), Sweden (88 deaths per million), and the UK as a whole (70 deaths per million).9 Since then, Scotland’s death rate in this age group has risen substantially to 260 per million in 2017.10

By comparison, Portugal’s rate was 3.86 deaths per million - just 27 people from a population almost twice the size of Scotland's.11 Although there are differences in the way drug-related deaths are registered, counted and defined in different countries, Scotland’s drug-related death rate remains 40-60 times that of Portugal on the above figures.

Data comparing the first six months of 2018 with 2017 suggest Scotland’s crisis is getting worse. For example, Ayrshire drug deaths increased by 119%, Forth Valley 93% rise, Edinburgh 45%, and Glasgow a 41% rise, from 95 to 134.12

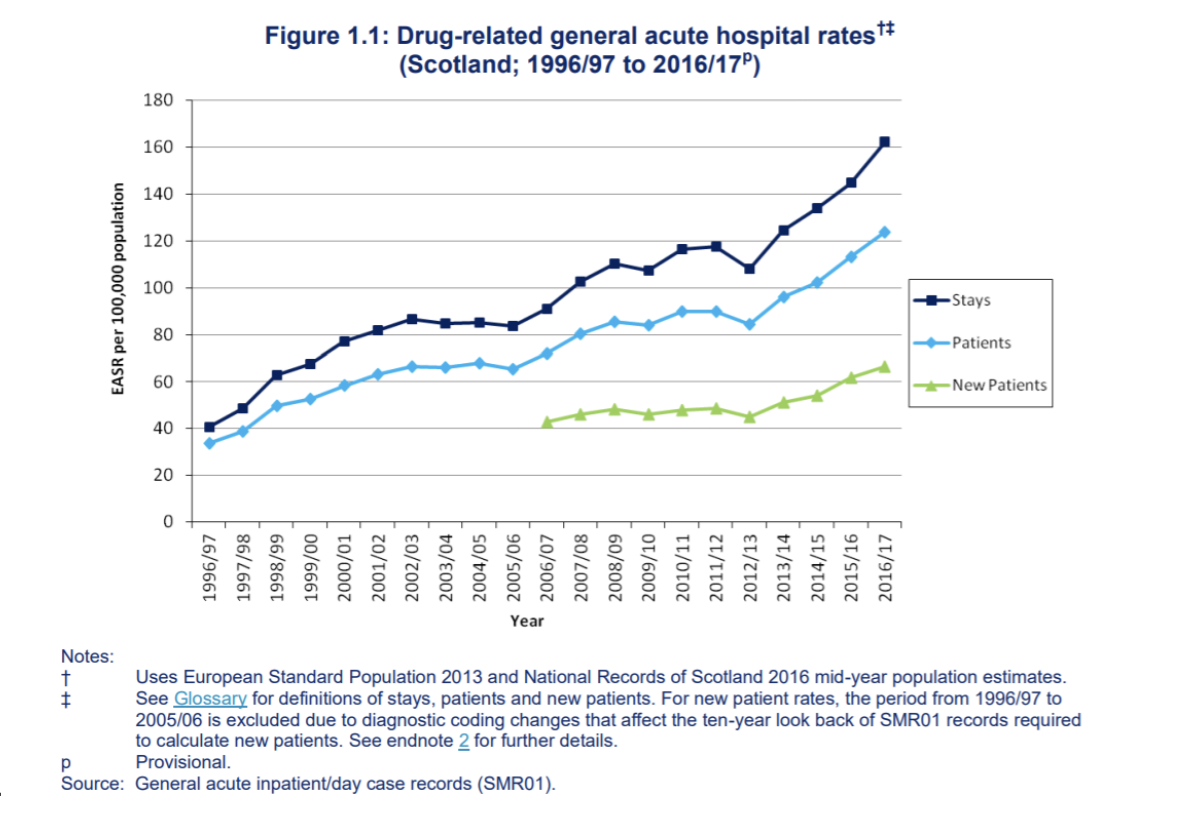

NHS Scotland drug-related hospital admissions data also underline the problem:13

According to the National AIDS Trust, the mortality rate for men with HIV was more than four times higher if they injected drugs.14 In Glasgow, there were 121 new HIV infections 2014-17 among people who inject drugs, a tenfold rise in infection rates, and this outbreak is not under control.15

The relationship between poverty, deprivation and problem drug use

Problematic drug use is not the inevitable consequence of initiation. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimates that around 11% of people who take illegal drugs globally suffer from drug use disorders.16 However, there is a well-evidenced link between problematic or high risk behaviours and risk factors including deprivation, inequality, parental neglect, emotional, physical or sexual abuse, histories of being in care, school exclusion, mental health problems, and unemployment, divorce or bereavement.17

In the most recent available data, approximately half of hospital patients with general acute or psychiatric stays in relation to drug misuse lived in the 20% most deprived areas in Scotland,18 which also saw half - 474 - of Scotland's drug-related deaths in 2017.19

Punitive ‘tough on drugs’ politics, and criminalisation of people who use drugs

The effects of drug policy need to be considered in the context of conditions surrounding health, welfare, mental health and social services, as well as the inequality, deprivation, and youth alienation that drives problematic use.

Current drug policy rests on two core assumptions: that supply-side enforcement can prevent or significantly reduce drug use, and that criminalisation of people who use drugs is an effective deterrent. Neither stands up to scrutiny.

In 2003 the Prime Minister’s Strategy Unit estimated that removing organised criminals from the drug trade would require consistent seizure rates of 60-80%.20 In Scotland estimated heroin seizures were around just 1% of the supply 2000-06.21 Seizures are an affordable cost of business, far less than legal tax rates or product losses (supermarkets waste 2% of food, fresh fish retailers 5% of products).22

In a high-profit market, criminal entrepreneurs always find ways to meet demand. The UK Government’s evaluation of its 2010-16 Drug Strategy acknowledges this, stating that ‘some enforcement activities can contribute to the disruption of drug markets...but the effects tend to be short-lived. Activity solely to remove drugs from the market, for example, drug seizures, has little impact on availability [...] illicit drug markets are resilient and can quickly adapt to even significant drug and asset seizures.’23 In March 2019, the UN System Coordination Task Team of the UN Chief Executive Board (representing the directors of all 31 UN agencies, and chaired by the Secretary General) concluded that; ‘The assumption that tougher law enforcement results in higher drug prices and therefore lowers the availability of drugs in the market is not supported by the empirical evidence.’24

The same is true for user-level deterrence. In 2006 the Science and Technology Select Committee concluded: ‘We have found no solid evidence to support the existence of a deterrent effect’.25 The Government said it ‘accepts that there is an absence of conclusive evidence’.26 In 2014 the Home Office compared approaches around the world, concluding there was no ‘obvious relationship between the toughness of a country’s enforcement against drug possession, and levels of drug use in that country’.27 The UK Drugs Strategy evaluation also noted ‘a lack of robust evidence as to whether capture and punishment serves as a deterrent for drug use’.28 This confirmed research by the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs,29 the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA),30 and the World Health Organization, which found ‘countries with stringent user-level illegal drug policies did not have lower levels of use than countries with liberal ones’.31

Criminalisation of people who use drugs does, however, create and exacerbate health harms. As the Royal Society for Public Health stated:

Criminalisation [of people who use drugs] leads directly to long-term health and wellbeing harm, including greater exposure to drugs in prison, severing of family relationships, and barriers to education and employment. This harm falls disproportionately on disadvantaged ethnic and socio-economic groups – who are far more likely to be charged for drug possession despite similar levels of use – exacerbating existing health inequalities...criminalisation fails to address underlying substance misuse issues and discourages those with an addiction from coming forward for treatment.32

The UK Government’s evaluation of its last Drug Strategy also accepts that:

There are potential unintended consequences of enforcement activity such as violence related to drug markets and the negative impact of involvement with the criminal justice system ...including unemployment and harm to families – parental imprisonment is a risk factor for child offending, mental health problems, drug abuse and unemployment amongst others.33

The Director of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) said that current drug policy creates ‘a huge criminal black market’ and by diverting funding to enforcement, has starved health care of scarce resources.34

Higher levels of enforcement are associated with hurried and higher-risk injecting over safer forms of administration;35 and displacement to other drugs36,37 leading to the use of novel drugs about which little is known.38

Criminalisation can create political and practical obstacles for health professionals to address health problems - as the so far unsuccessful efforts by the NHS in Scotland to open a Supervised Drug Consumption Facility show.

Trying to educate young people about drug risks, while seeking to arrest and punish them, leads to alienation and stigma, undermining outreach to those in need, as a recent EMCDDA report reiterated.39

Prohibition and unregulated supply

As well as fueling organised and acquisitive crime, criminal drug markets encourage the creation and use of more potent drugs that generate greater profits. Under 1920s US alcohol prohibition, consumption of beer gave way to spirits. Under current prohibition, opium has been replaced by heroin and fentanyl, and cocaine markets have evolved towards crack. The cannabis market is saturated with more potent varieties, and synthetic cannabinoids.

Unlike their legal market equivalents, illegally produced drugs lack health and safety information, and are of unknown (and variable) strength and purity, increasing risk of overdose, infection, and poisoning.40

What could Scotland learn from the approach taken to tackle drug misuse in other countries?

Core to reducing drug-related deaths is getting people with drug problems into treatment, and keeping them there until they have built the social assets and psychological resilience they need. That requires a well funded treatment system with routes in for the most marginalised for whom standard paths don’t work, and enhanced harm reduction measures that keep people alive until they can engage fully. An ideological focus on abstinence as the sole legitimate outcome of treatment, or stigmatisation through criminalisation, will push those in need away from help and drive up drug deaths. While many public services have borne cuts, underfunding treatment services is a false economy, creating much greater downstream costs.

Financial and political obstacles to innovative, cost-effective, harm-reduction interventions need to be removed. Transform has been closely involved in a number of these measures.

Decriminalise people who use drugs

The United Nations Chief Executives Board for Coordination - representing all 31 UN agencies - has called on member states to ‘promote alternatives to conviction and punishment ...including the decriminalization of drug possession for personal use’.41 Decriminalisation is supported by the Lancet42, the British Medical Journal43, the Royal Society for Public Health44, Royal College of Physicians, and British Medical Association. Decriminalisation of some or all drugs is now established policy in more than 25 countries.45 The Global Commission on Drug Policy has developed useful guidance on best practice.46

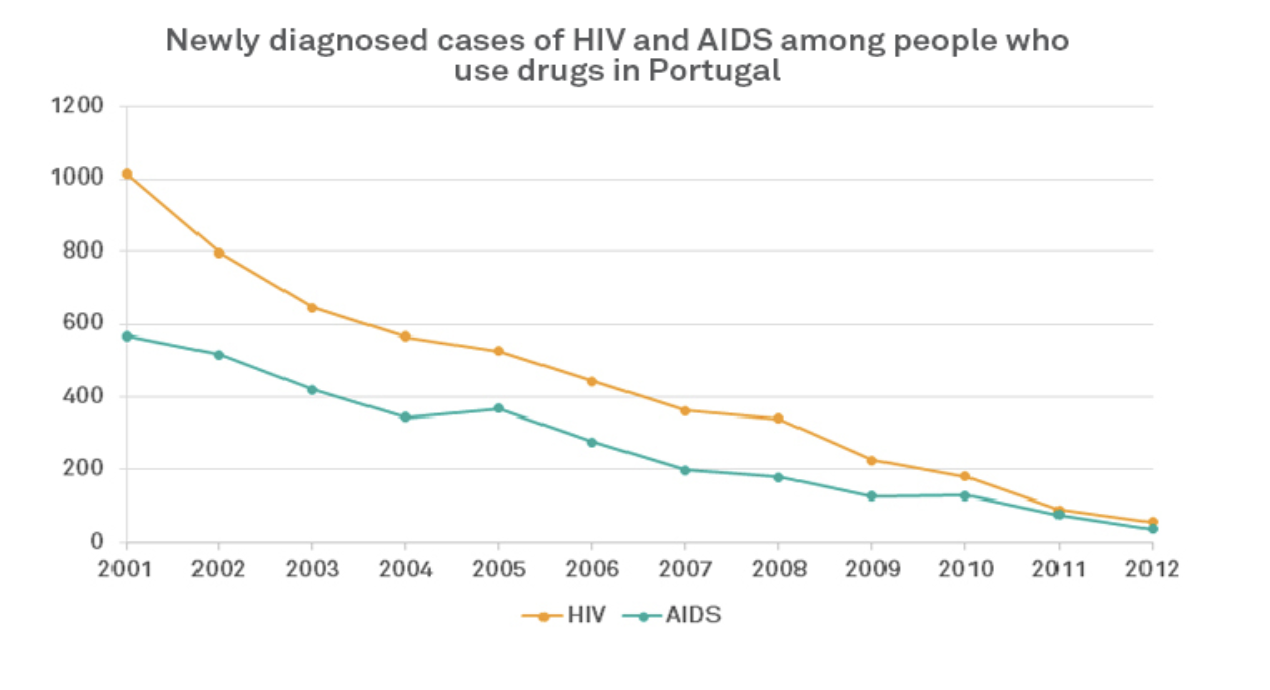

Since decriminalising possession and use of drugs in 2001, Portugal has seen problematic use, drug-related deaths and HIV infections fall significantly.47 Decriminalisation was the ‘critical enabler’ that released additional funding for treatment and allowed a more integrated health-based approach. The UK Government should enable Scotland to pursue Portugal’s de jure decriminalisation approach as a matter of urgency.

Source: Portugal Country Report 2018 http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/countries/drug-reports/2018/portugal_en and Drug Related Deaths in Scotland, NRS Scotland 2018 https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/statistics-and-data/statistics/statistics-by-theme/vital-events/deaths/drug-related-deaths-in-scotland

UK Diversion Schemes

While de jure decriminalisation of drugs is not currently within the gift of the Scottish Government, some of the benefits can be delivered through diversion schemes that Police Scotland, working with the Scottish Government, the Lord Advocate and the procurators fiscal could implement. Currently in Scotland, there is some useful diversion from courts, and Recorded Police Warnings for cannabis possession, but this is not enough. A number of UK police forces including Thames Valley (TVP), Avon and Somerset, and Durham have introduced schemes to divert people caught in possession of any drug for their own use (or in some cases for minor supply, or cultivation of cannabis offences) away from the criminal justice system This number is set to grow rapidly, with interest from police across Britain, and the Home Office and Ministry of Justice.

Diversion can guide people to an assessment, drug education courses, support or treatment, without harming life chances with a criminal record.48 This can be post-arrest, involving deferred prosecution ( Durham’s Checkpoint Scheme) or pre-arrest (Avon and Somerset, TVP). Evidence from the UK and globally shows diversion can:

- Prevent crime by reducing reoffending

- Significantly reduce the financial and resource burden on police forces

- Improve the physical and mental health of those diverted and engagement with treatment

- Improve the social and employment circumstances of those diverted.

Expand Heroin Assisted Treatment (HAT)49

We welcome that Glasgow is set to open a HAT clinic. But we would like to see this approach expanded to the 10% of the heroin using population for whom other treatment does not work, as in Switzerland, where HAT played a key role in reducing overdose deaths, HIV infections, use of illicit heroin, acquisitive crime, street dealing, and street drug litter, while being cost-effective. HAT was introduced in Switzerland in 1994, along with Supervised Drug Consumption Rooms, as part of a shift to a more health based approach following the failure of a criminal justice crack down to prevent large rises in drug related deaths, and other harms.50,51

UK HAT trials found acquisitive crimes per user fell by two-thirds - around 13,000 fewer crimes per year by the 40 people on the trial.52 Swiss research suggests the 10-15% of people eligible for HAT were using 30-60% of all illegal heroin.52 Taking this group out of the criminal market reduced Organised Crime Group income (for comparison 4% heaviest drinkers in the UK provide 23% of alcohol industry revenue).54 Prior to joining the HAT programme, many participants had been small-scale heroin dealers to fund their own use. Swiss police data showed an 80% fall in the number of small scale heroin dealing offences committed by HAT participants after 24 months. The programme disrupted the function of the heroin market and reduced initiation new users.55

Sources: Addiction Monitoring in Switzerland, Federal Office of Public Health http://www.suchtmonitoring.ch/fr/3/7.html?opioides-mortalite

Drug Related Deaths in Scotland, NRS 2018 https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/statistics-and-data/statistics/statistics-by-theme/vital-events/deaths/drug-related-deaths-in-scotland

Introduce Drug Safety Testing56

Contamination and variable strength are key drivers of drug-related fatalities. Drug safety testing services allow people to know what they have bought. This reduces the risk of overdose or poisoning, and provides an opportunity to target health advice and monitor drug content and trends.57 Where exceptionally risky drugs are found, medical services can be alerted and public warnings issued.58 Such services have been running in a number of European countries for over 20 years.

After a number of informal UK projects in festivals and city centres since 201659, the Home Office recently licensed a pilot drug safety testing facility in Weston-Super-Mare, delivered by the national treatment provider Addaction. This pilot service was also accessed by people who use heroin.

Supervised Drug Consumption Rooms (DCRs)

DCRs, which engage hard to reach populations in treatment, have prevented overdose deaths and HIV infections across the world, and are recommended by the ACMD.60 However, they remain blocked by the UK Home Office.61 This is despite the Home Office acknowledging the public health benefits, for example in this letter to Glasgow City Council, which had unanimously asked permission to open one:62

The Government’s own report, Drugs: International Comparators (2014), acknowledges that there is some evidence for the effectiveness of drug consumption rooms in addressing the problems of public nuisance associated with open drug scenes, and in reducing health risks for drug users. The Government’s Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) has also provided additional evidence based on studies of the effectiveness of facilities in Vancouver and Sydney, noting that they reduce injecting risk behaviours and overdose fatalities. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) too finds that drug consumption facilities have the ability to reach and maintain contact with high-risk drug users who are not ready or willing to quit drug use.63 Home Office Drug Legislation Team, 2018

The Home Office claim that DCRs would be too difficult to police was subsequently addressed in a letter to the Home Office minister Victoria Atkins, from three Police and Crime Commissioners who had visited operational DCRs. They assured her UK police have the requisite knowledge and skills to manage any issues arising from a DCR, as they do with existing harm reduction measures.64

The UK Government’s current main argument for opposing DCRs is that by allowing illegal drug use, they support the illegal drug market. But the reverse is true. Without a DCR, people will still buy the same quantity of drugs - but often use them alone. Indeed, DCRs can reduce the size of the illegal drugs market, as they provide an opportunity to encourage people into treatment - which will mean they will use less heroin or crack. According to the EMCDDA:

There is no evidence to suggest that the availability of safer injecting facilities increases drug use or frequency of injecting. These services facilitate rather than delay treatment entry and do not result in higher rates of local drug-related crime.65

The UK and Scottish Governments should explore options for regulation of drugs production and supply

Handing the drugs market to criminals through prohibition is a key driver of health and social harms. Legally regulating drug markets is now a reality. Beyond the HAT model, multiple jurisdictions are exploring or implementing regulated markets for cannabis, including Uruguay, Canada, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand and 11 US states. Coca is now regulated in Bolivia, and legal regulation of NPS has been considered in New Zealand. Transform has produced a range of proposals and case studies for responsible regulation, and advised many of the countries where this has taken place.66 We note that in 2002, and again in 2012 the Home Affairs Select Committee recommended:

[T]hat the [UK] Government initiates a discussion within the Commission on Narcotic Drugs of alternative ways—including the possibility of legalisation and regulation—to tackle the global drugs dilemma67

Would further devolution of powers enable the Scottish Government more effectively address drugs misuse in Scotland and tailor their approach to Scotland’s needs?

Calling for a Health Emergency to be declared

Scottish politicians have rightly described drug-related deaths as a health emergency. However, formally declaring a Health Emergency, and authorising accompanying emergency powers, is not a devolved power. Chapter 6 of Preparing Scotland states: ‘The decision to use, or not use, emergency powers, is a matter for the UK Government.’ But the powers could be used if a situation threatens ‘serious damage to human welfare in the UK, a devolved territory or English region’. And "...the decisive factor will be whether existing powers that could be used to deal with it are insufficient or ineffective.’68

The Scottish Government does not have the power to open supervised drug consumption rooms, or deliver de jure decriminalisation of people who use drugs. But that power could be granted if the UK Government declared a Health Emergency at Scotland’s request and created the relevant emergency regulations as part of a set of measures to address drug deaths.

The UK Government should legislate in the normal way as it would be preferable for all areas across the UK to benefit from both decriminalisation and DCRs. But allowing Scotland to pilot DCRs, and decriminalisation under emergency powers, could avoid directly affecting the legal situation in other parts of the UK.

Recommendations

The UK and Scottish Governments should work together to re-centre drug policy towards evidence-based public health and harm reduction approaches, and away from failed punitive enforcement, repressive approaches and a ‘war on drugs’ ideology.

Responsibility for UK drug policy should move from the Home Office to the Department of Health to help ensure the UK has a joined up, health-led approach.

The UK Government should bring forward UK-wide de jure decriminalisation of small scale non-violent drug offences including possession for personal use, and minor supply or cultivation of cannabis offences. Alternatively, it should devolve the powers needed for Scotland to do so either permanently, or on a pilot basis, for example through special powers after declaring a National Health Emergency in Scotland.

Pending decriminalisation of people who use drugs, the Scottish Government, UK Home Office and Department of Health should work with police forces to develop best practice guidelines for diversion schemes to maximise the public health and crime reduction benefits.

The UK Government should devolve decision-making over opening supervised drug consumption rooms (DCRs) to local areas - including Scotland - as it has done for drug safety testing. This would allow the opening of pilots, with a view to amending the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 if evaluation demonstrates efficacy.

The UK Government should share its expertise and knowledge, and encourage the Scottish Government to roll-out out drug safety testing, including in city centres for people who use heroin.

The UK Government and Scottish Government should play a leadership role in bringing together stakeholders, and should provide seed-funding for national upscaling of HAT to meet need. Long-term sustainable funding should be delivered through local cost-sharing between public services and businesses that are shown to benefit financially. All funding should be additional to existing resources for drug treatment services.

UK Government should work with devolved administrations to establish an independent expert cross-party parliamentary commission of inquiry to explore options for, and make recommendations on, the legal regulation of currently illegal drugs.

References:

- House of Commons Library (2018), ‘Public Health Model to reduce youth violence’ http://researchbriefings.files...

- ONS (2018) Deaths related to drug poisoning in England and Wales: 2017 registrations https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsrelatedtodrugpoisoninginenglandandwales/2017registrations

- In 2017 there were 2503 illegal drug related deaths in England and Wales, ONS (2018). Deaths related to drug poisoning in England and Wales: 2017 registrations, p. 3 https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsrelatedtodrugpoisoninginenglandandwales/2017registrations ; 934 drug-related deaths in Scotland in 2017, NRS (3 July 2018)https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/files/statistics/drug-related-deaths/17/drug-related-deaths-17-pub.pdf ; and 136 in Northern Ireland, NI Statistics and Research Agency Drug-related deaths 2007-17, (March 2019) https://www.nisra.gov.uk/publications/drug-related-and-drug-misuse-deaths-2007-2017

- EMCDDA (2018), European Drug Report Trends and Developments, p.75 http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/sy...

- National Records Scotland (2018). Drug-related deaths in Scotland, 2018, p.6 https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/files/statistics/drug-related-deaths/17/drug-related-deaths-17-pub.pdf

- National Records Scotland (2018). Drug-related deaths in Scotland, 2018, p. 56 https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/files/statistics/drug-related-deaths/17/drug-related-deaths-17-pub.pdf

- National Records Scotland (2018). Drug-related deaths in Scotland, 2018, p. 52 https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/files/statistics/drug-related-deaths/17/drug-related-deaths-17-pub.pdf

- EMCDDA (2018), European Drug Report Trends and Developments, p.75 http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/8585/20181816_TDAT18001ENN_PDF.pdf

- NRS Scotland: “The resulting drug-induced death rate (aged 15-64) for Scotland is 175 per million population. This appears to be higher than for any of the countries shown in the EMCDDA table. The next highest rates are for Estonia (132 per million) and Sweden (88 per million)” https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/files//statistics/drug-related-deaths/17/drug-related-deaths-17-pub.pdf#page=6

- National Records Scotland (2018). Drug-related deaths in Scotland, 2018, p. 56 https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/files/statistics/drug-related-deaths/17/drug-related-deaths-17-pub.pdf NB using the EMCDDA definitions of drug related death this number would be slightly lower.

- EMCDDA (2018). Portugal: Country Drug Report 2018. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/country-drug-reports/2018/portugal_enhttp://www.emcdda.europa.eu/countries/drug-reports/2018/portugal/drug-harms_en

- Turriff, C (2018) ‘Holyrood told to act as drug death rate soars’. The Times https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/holyrood-told-to-act-as-drug-death-rate-soars-swqkcpdcw

- NHS Scotland Information Service Division (2017) Drug-Related Hospital Statistics Scotland 2016/17 p3.https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Drugs-and-Alcohol-Misuse/Publications/2017-09-26/2017-09-26-DRHS-Report.pdf

- National AIDS Trust (2019). ‘Drug related deaths in England https://www.nat.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/drug_related_deaths_in_england.pdf

- Rise in HIV infections in people who inject drugs - update 2018 https://www.nhsggc.org.uk/your-health/public-health/public-health-protection-unit-phpu/bloodborne-virus/hiv/rise-in-hiv-infections-in-people-who-inject-drugs-update-2018/#

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2018). World drugs report – executive summary, p.7

- ACMD, 2018, ‘What are the risk factors that make people susceptible to substance misuse problems and harms?’ https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/761123/Vulnerability_and_Drug_Use_Report_04_Dec_.pdf; ACMD, 2006, ‘Pathways to Problems: Hazardous use of tobacco, alcohol and other drugs by young people in the UK and its implications for policy’ https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/119053/Pathwaystoproblems.pdf; ACMD 1998 ‘Drug Misuse and the Environment’ - not currently available online, although the summary is available here: https://www.drugwise.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/ACMD-environment.pdf

- NHS Scotland Information Service Division (2017) Drug-Related Hospital Statistics Scotland 2016/17 p4.https://www.isdscotland.org/He...

- Iain McPhee, Barry Sheridan, Steve O’Rawe, (2019) "Time to look beyond ageing as a factor? Alternative explanations for the continuing rise in drug related deaths in Scotland", Drugs and Alcohol Today, Vol. 19 Issue: 2, pp.78, https://doi.org/10.1108/DAT-06...

- PM Strategy Unit (2003). Drugs Report Phase one – Understanding the issues, p. 73 https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http:/www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/media/cabinetoffice/strategy/assets/drugs_report.pdf

- McKeganey, N. et al. (2009). Heroin seizures and heroin use in Scotland. Journal of Substance Use 14.3-4, pp. 240-249 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14659890902960706?scroll=top&needAccess=true&journalCode=ijsu20

- Steven Butts, head of corporate responsibility for Morrisons, evidence to Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee, Jan 2017 http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/environment-food-and-rural-affairscommittee/food-waste/oral/45673.pdf; WRAP (2011). Resource Maps for Fish across Retail & Wholesale Supply Chains http://www.wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Resource%20Maps%20for%20Fish%20across%20Retail%20and%20Wholesale%20Supply%20Chains.pdf

- HM Government (2017). An evaluation of the Government’s Drug Strategy 2010, p.101 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/628100/Drug_Strategy_Evaluation.PDF

- UN system coordination Task Team on the Implementation of the UN System Common Position on drug-related matters (2019)What we have learned over the last ten years; A summary of knowledge acquired and produced by the UN system on drug-related matters https://www.unodc.org/documents/commissions/CND/2019/Contributions/UN_Entities/What_we_have_learned_over_the_last_ten_years_-_14_March_2019_-_w_signature.pdf

- House of Commons Science and Technology Committee (2006). Drug classification: making a hash of it?’ Fifth Report of Session 2005–06, p.36 https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200506/cmselect/cmsctech/1031/1031.pdf

- HM Government (2006). The Government reply to the fifth report from the house of Commons Science and technology Committee Session 2005-06 HC 1031 ‘Drug classification: making a hash of it?’’, p.18 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/drug-classification-making-a-hash-of-it

- Home Office (2011). Drugs: International Comparators, p.51 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/drugs-international-comparators

- HM Government (2017). An evaluation of the Government’s Drug Strategy 2010, p.101 https://assets.publishing.serv...

- Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (2016). 2016 Drug Strategy: ACMD comments. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/627980/ACMD_Drug_Strategy_Response__2016__1_Feb_2016.pdf

- EMCDDA (2011). Looking for a relationship between penalties and cannabis use - EMCDDA Annual Report, p.45 http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/online/annual-report/2011/boxes/p45

- Degenhardt L. et al. (2008) ‘Toward a Global View of Alcohol, Tobacco, Cannabis, and Cocaine Use: Findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys’, PLoS Medicine. www.plosmedicine.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pmed.0050141

- RSPH statement summarising its report ‘Taking a new line on drugs’ Royal Society for Public Health, supported by the Faculty for Public Health, 2016 https://www.rsph.org.uk/about-...

- HM Government (2017). ‘An evaluation of the Government’s Drug Strategy 2010.’ Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/628100/Drug_Strategy_Evaluation.PDF

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2008). ‘Making drug control 'fit for purpose': building on the UNGASS decade’. Available at:http://www.unodc.org/documents/commissions/CND-Session51/CND-UNGASS-CRPs/ECN72008CRP17.pdf

- Rhodes, T. (20050. The social structural production of HIV risk among injecting drug users. Social Science and Medicine, 61.5, pp. 1026-44

- Boyce, N. (2011). Health warnings for people who use heroin. The Lancet, 377:9761, pp. 193-4

- Measham, F. et al. (2010). Tweaking, bombing, dabbing and stockpiling: the emergence of mephedrone and the perversity of prohibition. Drugs and Alcohol Today 10.1

- Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (2011). Consideration of the Novel Psychoactive Substances (“Legal Highs”)’ http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/p... acmdnps2011?view=Binary

- EMCDDA (2019) Technical report: drug prevention - exploring a systems perspective. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/10403/EMCDDA%20Technical%20report_Drug%20prevention%20systems.pdf

- Jones, L. et al. (2011). A summary of the health harms of drugs. NationalTreatment Agency, p. 11. http://www.nta.nhs.uk/uploads/healthharmsfinal-v1.pdf; Cole, C. et al. (2010) Cut: A Guide to the Adulterants, Bulking agents and other Contaminants found in Illegal Drugs. http://www.cph.org.uk/showPubl...

- United Nations (2019), ‘United Nations Chief Executives Board for Coordination - second regular session of 2018’, p. 14. Available at https://www.unsceb.org/CEBPubl...

- The Lancet (2016) ‘Reforming international drug policy’https://www.thelancet.com/jour...

- BMJ (2018) ‘Drugs should be legalised, regulated, and taxed’ https://www.bmj.com/content/36...

- RSPH (2018) ‘Royal College of Physicians backs RSPH calls on drug reform’ https://www.rsph.org.uk/about-...

- Eastwood N, Fox E & Rosmarin A (2016), ‘A Quiet Revolution: Drug Decriminalisation Across the Globe’ https://www.release.org.uk/pub...

- Global Commission on Drugs Policy (2016), ‘Advancing Drug Policy Reform: a new approach to decriminalization’ http://www.globalcommissionond...

- Royal Society for Public Health (2016). ‘Taking a new line on drugs’, p. 21

- Existing schemes include Durham, Avon and Somerset, and Thames Valley

- Transform (2018). Heroin Assisted Treatment (HAT) - saving lives, improving health, reducing crime. Available at: https://transformdrugs.org/wp-...

- Transform (2017), Heroin Assisted treatment (HAT): Saving lives, Improving Lives, Reducing Crime https://transformdrugs.org/product/heroin-assisted-treatment-hat-saving-lives-improving-health-reducing-crime/

- OSF (2020), ‘From the Mountaintops: What the World Can Learn from Drug Policy Change in Switzerland’https://www.opensocietyfoundat...

- The ~40 people on HAT committed 1731 crimes in the 30 days prior to entering the UK HAT (RIOTT) trial treatment. After 6 months, this fell to 547 crimes (a reduction of over 2/3rds or 1,184 crimes per month). Kings Health Partners and Action on Addiction (2009). ‘Untreatable or just hard to treat? Results of the Randomised Injectable Opioid Treatment Trial (RIOTT)’, p.3 http://fileserver.idpc.net/library/Untreatable%20or%20just%20hard%20to%20treat.pdf

- Killias, M. and Aebi, M. (2000) ‘The impact of heroin prescription on heroin markets in Switzerland’, Crime Prevention Studies, vol. 11, pp. 83-99.

- Aveek Bhattacharya et al, (2018) How dependent is the alcohol industry on heavy drinking in England? https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/add.14386

- Killias, M. and Aebi, M. (2000) ‘The impact of heroin prescription on heroin markets in Switzerland’, Crime Prevention Studies, vol. 11, pp. 83-99.

- Transform (2018). Drug safety testing: saving lives, increasing awareness. Available at: https://transformdrugs.org/wp-...

- F.C. Measham, ‘Drug safety testing, disposals and dealing in an English field: Exploring the operational and behavioural outcomes of the UK’s first onsite ‘drug checking’ service’ International Journal of Drug Policy, Available online 9 December 2018https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0955395918302755

- EMCDDA (2017), ‘Drug checking as a harm reduction tool for recreational drug users: opportunities and challenges’ p.4http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/attachments/6339/EuropeanResponsesGuide2017_BackgroundPaper-Drug-checking-harm-reduction_0.pdf

- See: https://wearetheloop.org/

- ACMD (2016) ‘Reducing opioid-related deaths in the UK’ https://www.gov.uk/government/...

- Transform (2017). ‘Drug consumption rooms: saving lives, making communities safer’,

- Safe drug consumption rooms – Motion approved. (2018) http://www.glasgow.gov.uk/Councillorsandcommittees/viewSelectedDocument.asp?c=P62AFQDN2U0G0GUTT1

- Letter to Glasgow City Council from Home Office Drugs Legislation Team (2018) Reported on Glasgow City Council website https://www.glasgow.gov.uk/ind... Copy of letter available on request.

- Letter from PCCs David Jamieson, Ron Hogg and Arfon Jones to the Home Office (2018) STATEMENT ON ‘REDUCING OPIOID-RELATED DEATHS IN THE UK REPORT – FURTHER RESPONSE REGARDING DRUG CONSUMPTION ROOMS’ available on request

- European Monitoring Centre on Drugs and Drug Addiction, ‘Drug consumption rooms: an overview of provision and evidence’ http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/pods/drug-consumption-rooms_en

- See: https://transformdrugs.org/publications/

- See: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200102/cmselect/cmhaff/318/31815.htm and https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201213/cmselect/cmhaff/184/18413.htm

- Ready Scotland (2016), ‘Preparing Scotland: Scottish Guidance on Resilience, Philosophy, Principles, Structures and Regulatory Duties’ https://www.readyscotland.org/media/1166/preparing-scotland-philosophy-principles-structures-and-regulatory-duties-20-july-2016.pdf