6th July 2020

The Government has launched Phase 2 of the Carol Black report into drugs, with the provisional findings due in October and the final report expected in December. The first report of the Black Review laid out, in great detail, the failures of current drug policy: increasing health harms, needless criminalisation, rising social inequalities, slashed funding for treatment, more violence and more exploitation.

The focus of Phase 2 is prevention and recovery. How both terms are understood will be critical, and let’s hope they aren’t defined narrowly. We desperately need a comprehensive approach to prevention, and we need a non-dogmatic approach to recovery - one which not only recognises ‘recovery’ can take many forms but that keeping people alive and well through harm reduction is absolutely vital.

We also need concrete steps to better funding, and to a system that is finally able to effectively connect substance use, mental health and housing services in ways that recognise the complex drivers of harm – and which finally address the problem of people with ongoing drug issues being excluded from mental health services or housing.

The Government has, however, explicitly ruled out any consideration of drug legislation from the review. While predictable (the same exclusion was applied to phase 1), this restriction is patently absurd. It is like commissioning a report on climate change, but telling investigators not to consider the role of carbon emissions.

It means that the review will only be able to propose limited alternatives to the criminalisation and imprisonment that so evidently impacts on mental health, life chances and, indeed, substance use. Similarly, while it may speak to the impact of drug policing on individuals or communities, and its role in reinforcing structural racism, it will not be able to consider whether the Misuse of Drugs Act itself is a cause of these problems. It will have to treat the exploitation of people in the supply chain – the thousands of vulnerable children and adults caught up in county lines, or trafficked into cannabis farms – as only a consequence of consumer choices, not an obvious feature of the entirely unregulated markets inevitable under prohibition.

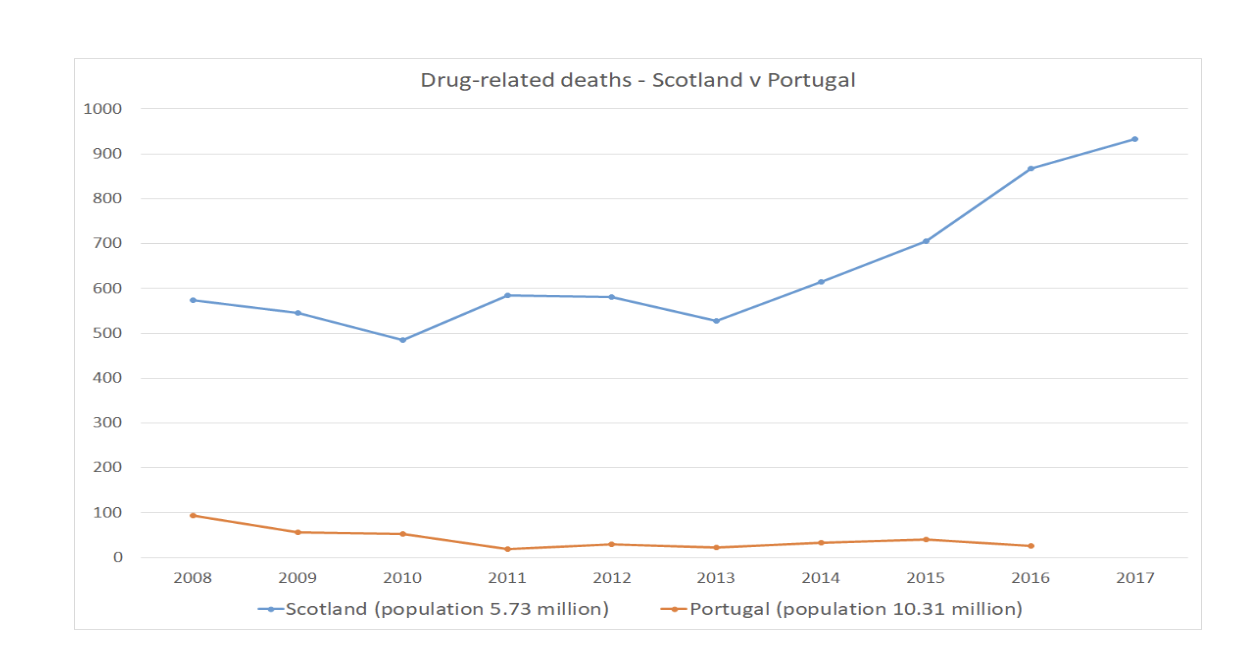

It means lessons from the decriminalisation in Portugal, or the legal regulation of cannabis in Canada and elsewhere, may be considered but can’t be applied comprehensively. It means that even if the system itself is identified as a structural driver of harms, proposals for reform of that system that might mitigate those harms are off limits. It places a barrier on any attempt to explore the upstream causes of the problems that the review sets out to resolve. In any other area of health policy, such a limitation would be considered absurd.

To put this anomaly in context, it’s worth noting that Dame Carol has her hands tied in a way that the Government’s independent expert body, the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, does not. The ACMD’s terms of reference, established within the Misuse of Drugs Act itself, require them to offer ministers ‘advice on measures (whether or not involving alteration of the law) which in the opinion of the Council ought to be taken for preventing the misuse of such drugs or dealing with social problems connected with their misuse’ (emphasis added)

We don’t wish to undermine the review, and hope that it achieves real change within its limited scope. Phase 1 showed that Dame Carol is committed to a thorough and insightful approach. It is unfortunate that the team’s hands are tied in this way, but we will work to ensure that consideration of the law remains central to this vital debate.

Author: James Nicholls, CEO Transform Drug Policy Foundation